JustInTime (Talk | contribs) |

|||

| (92 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

<title>About Us</title> | <title>About Us</title> | ||

<link href='http://fonts.googleapis.com/css?family=Lato' rel='stylesheet' type='text/css'> | <link href='http://fonts.googleapis.com/css?family=Lato' rel='stylesheet' type='text/css'> | ||

| − | |||

<style type='text/css'> | <style type='text/css'> | ||

#top_title, | #top_title, | ||

| Line 79: | Line 78: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="box3 left biosafety" href="https://2017.igem.org/Team:TAS_Taipei/Safety"> | <div class="box3 left biosafety" href="https://2017.igem.org/Team:TAS_Taipei/Safety"> | ||

| − | <h1> | + | <h1>Safety</h1> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="box3 left about" href="https://2017.igem.org/Team:TAS_Taipei/Team"> | <div class="box3 left about" href="https://2017.igem.org/Team:TAS_Taipei/Team"> | ||

| Line 94: | Line 93: | ||

<div class="container"> | <div class="container"> | ||

<h1>Prototype</h1> | <h1>Prototype</h1> | ||

| − | <h4>Design, Build and Test: Putting our project to work | + | <h4>Design, Build, and Test: Putting our project to work</h4> |

</div> <a href="#cv"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/4/4a/T--TAS_Taipei--Chevron_500px_200ppi.png" alt="test" id="chevron"></a> </div> | </div> <a href="#cv"><img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/4/4a/T--TAS_Taipei--Chevron_500px_200ppi.png" alt="test" id="chevron"></a> </div> | ||

<!--全版面大型看板結尾--> | <!--全版面大型看板結尾--> | ||

<div class="cv" id="cv"> | <div class="cv" id="cv"> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <nav class="pageNav col-lg- | + | <nav class="pageNav col-lg-1_5"> |

<ul class="nav"> | <ul class="nav"> | ||

| − | <li> <a href="#WWT" class="pageNavBig">WASTEWATER | + | <li> <a href="#WWT" class="pageNavBig">WASTEWATER TREATMENT</a> </li> |

| − | <li> <a href="#what" class="pageNavSm">What is | + | <li> <a href="#what" class="pageNavSm">What is the process?</a> </li> |

<li> <a href="#biosafety" class="pageNavSm">Biosafety</a> </li> | <li> <a href="#biosafety" class="pageNavSm">Biosafety</a> </li> | ||

| − | <li> <a href="#PR" class="pageNavBig"> | + | <li> <a href="#PR" class="pageNavBig">PR CONSIDERATIONS</a> </li> |

| − | <li> <a href="#biofilm" class="pageNavBig"> | + | <li> <a href="#PRApply" class="pageNavSm">Applying PR in a WWTP Model</a> </li> |

| − | <li> <a href="#volume" class="pageNavSm">Volume | + | <li> <a href="#biofilm" class="pageNavBig">BIOFILM CONSIDERATIONS</a> </li> |

| − | <li> <a href="#SA" class="pageNavSm">Surface Area | + | <li> <a href="#volume" class="pageNavSm">Volume</a> </li> |

| + | <li> <a href="#SA" class="pageNavSm">Surface Area</a> </li> | ||

<li> <a href="#prototype" class="pageNavBig">BIOFILM PROTOTYPE</a> </li> | <li> <a href="#prototype" class="pageNavBig">BIOFILM PROTOTYPE</a> </li> | ||

<li> <a href="#max" class="pageNavSm">Maximize NP-Biofilm Contact Area</a> </li> | <li> <a href="#max" class="pageNavSm">Maximize NP-Biofilm Contact Area</a> </li> | ||

<li> <a href="#infra" class="pageNavSm">Maximize Adaptability to Existing Infrastructure</a> </li> | <li> <a href="#infra" class="pageNavSm">Maximize Adaptability to Existing Infrastructure</a> </li> | ||

| − | <li> <a href="#WWTPModel" class="pageNavSm">Biofilm | + | <li> <a href="#WWTPModel" class="pageNavSm">Applying Biofilm in a WWTP Model</a> </li> |

| − | <li> <a href="#ref" class="pageNavBig"> | + | <li> <a href="#ref" class="pageNavBig">REFERENCES</a> </li> |

</ul> | </ul> | ||

</nav> | </nav> | ||

| − | <div class="white col-lg-2"> | + | <div class="white col-lg-2"> </div> |

<div class="col-lg-10"> | <div class="col-lg-10"> | ||

<!-- header --> | <!-- header --> | ||

| Line 123: | Line 123: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <h4 class="para col-lg-12">It is estimated that about 95% of nanoparticles used in consumer products end up in wastewater (<i> | + | <h4 class="para col-lg-12">It is estimated that about 95% of nanoparticles (NPs) used in consumer products end up in wastewater (<i>Mueller & Nowack.</i> 2008). <b>Our goal is to apply our biofilm and Proteorhodopsin (PR) bacteria in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) to remove most NPs</b> before the effluent is released into the environment. </h4> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row this_border"></div> | <div class="row this_border"></div> | ||

</header> | </header> | ||

<section class="main"> | <section class="main"> | ||

| − | <div class="row" id=" | + | <div class="row" id="WWT"> |

<h1 class="title2 col-lg-12">WASTEWATER TREATMENT</h1> | <h1 class="title2 col-lg-12">WASTEWATER TREATMENT</h1> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="row" id="what"> | ||

| + | <h1 class="section-title col-lg-12">What is the process?</h1> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="image_container col-lg-10 col-lg-offset-1"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/6/6e/T--TAS_Taipei--WWTPFlow.jpg" alt="test" id="group"> | ||

| + | <h4 class="subtitle">Figure 5-1<b> Typical wastewater treatment process. </b><span class="subCred">Figure: Yvonne W.</span></h4> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div><br> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | < | + | <h4 class="para col-lg-12">When wastewater enters a plant, the first step is to remove coarse solids and large materials using a grit screen (figure 5-1). The water can then be processed in three main stages: Primary, Secondary, and sometimes Tertiary Treatment (Pescod 1992). In <b>Primary Treatment</b>, heavy solids are removed by sedimentation while floating materials (such as oils) can be taken out by skimming. However, dissolved materials and colloids—small, evenly dispersed solids such as NPs—are not removed here (Pescod 1992). <b>Secondary Treatment</b> generally involves the use of aeration tanks, where aerobic microbes help to break down organic materials. This is also known as the activated sludge process (Davis 2005). In a subsequent sedimentation step, the microbes are removed and the effluent is disinfected (often by chlorine or UV) before it is released into the environment. In certain WWTPs, wastewater may go through <b>Tertiary Treatment</b>, an advanced process typically aimed to remove nitrogen and phosphorous, and assumed to produce an effluent free of viruses (Pescod 1992). However, Tertiary Treatment requires additional infrastructure that is expensive and complex, limiting its global usage (Pescod 1992; Malik 2014). </h4> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> | + | <h4 class="para col-lg-12">Ideally, we would like to remove NPs from all systems, so we visited two different types of WWTPs: a local urban facility in Dihua, Taipei, and a smaller rural facility in Boswell, Pennsylvania. We found that wastewater in the two plants is treated using very similar processes (figures 5-2 and 5-3). We also contacted Thomas J. Brown, the Water Program Specialist of the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, and asked him if there were differences between rural and urban plants that we should consider when thinking about implementing our project. He responded, <b>“[t]he heart of the treatment process is the biological process used for treatment; the biology remains the same regardless of facility size.”</b> Thus, in both types of WWTPs, we want to apply our engineered bacteria in the Secondary Treatment step—either in aeration tanks or in the sedimentation tank. |

| + | </h4> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

<div class="image_container col-lg-10 col-lg-offset-1"> <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/e/e1/T--TAS_Taipei--DihuaDiagram-new.jpg" alt="test" id="group"> | <div class="image_container col-lg-10 col-lg-offset-1"> <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/e/e1/T--TAS_Taipei--DihuaDiagram-new.jpg" alt="test" id="group"> | ||

| − | <h4 class="subtitle"> | + | <h4 class="subtitle"><b>Figure 5-2 Dihua WWTP sewage process. </b><span class="subCred">Figure: Christine C.</span></h4> |

</div> | </div> | ||

</div><br> | </div><br> | ||

| Line 149: | Line 159: | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

<div class="image_container col-lg-10 col-lg-offset-1"> <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/2/2f/T--TAS_Taipei--BoswellDiagram-new.jpg" alt="test" id="group"> | <div class="image_container col-lg-10 col-lg-offset-1"> <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/2/2f/T--TAS_Taipei--BoswellDiagram-new.jpg" alt="test" id="group"> | ||

| − | <h4 class="subtitle"> | + | <h4 class="subtitle"><b>Figure 5-3 Boswell WWTP sewage process. </b><span class="subCred">Figure: Christine C.</span></h4> |

</div> | </div> | ||

</div><br> | </div><br> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

<video controls="" class="col-lg-10 col-lg-offset-1"> | <video controls="" class="col-lg-10 col-lg-offset-1"> | ||

| − | <source src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/ | + | <source src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/3/3a/T--TAS_Taipei--BoswellVid.mp4" type="video/mp4"> Your browser does not support the video tag. |

</video> | </video> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | <div class="row" id=" | + | <div class="row" id="biosafety"> |

<h1 class="section-title col-lg-12">Biosafety</h1> | <h1 class="section-title col-lg-12">Biosafety</h1> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> We | + | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> We used a safe and common lab strain of <i>E. coli</i>, K-12, as our chassis (Environmental Protection Agency 1977). In both approaches, our constructs do not express proteins associated with virulence: PR is a transmembrane protein that commonly exists in marine bacteria, and for biofilm production we were careful to avoid known virulence factors such as alpha hemolysins (<i>Fattahi et al.</i> 2015). Most importantly, <b>biosafety is built into WWTPs</b>. Before treated effluent is released back into the environment, it must go through a final disinfection step, where chlorine, ozone, or UV radiation are used to kill microbes still present in the wastewater (Pescod 1992). |

| − | + | </h4> | |

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | <div class="row" id=" | + | <div class="row" id="PR"> |

| − | <h1 class="title2 col-lg-12"> | + | <h1 class="title2 col-lg-12">PR CONSIDERATIONS</h1> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> During our visit to Dihua WWTP, the chief engineer informed us that they use the activated sludge process, which uses aerobic microbes to digest organic matter in aeration tanks. The steady influx and mixing of air provide oxygen favorable to aerobic microbes; the turbulent water | + | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> During our visit to Dihua WWTP, the chief engineer informed us that they use the activated sludge process, which uses aerobic microbes to digest organic matter in aeration tanks. The steady influx and mixing of air provide oxygen favorable to aerobic microbes; the turbulent water also increases the probability of PR binding to citrate-capped NPs (CC-NPs). Thus, <b>we envision directly adding PR <i>E. coli</i> into existing aeration tanks</b>. In addition, as part of the activated sludge process, WWTPs regularly cycle microbe-rich sludge back into aeration tanks to maintain the microbial population (figure 5-1). Ideally, this would stabilize the PR bacterial population in aeration tanks, allowing this system to be <b>low-maintenance and easily adaptable to existing infrastructure</b>. |

| − | + | </h4> | |

| − | + | </div> | |

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> To facilitate the application of PR bacteria in WWTPs, our modeling team created a calculator that informs WWTP managers the amount of PR bacteria they need to trap their desired amount of CC-NPs based on our experimental results and the conditions of their WWTP. Learn more about PR <a href="https://goo.gl/gu91Wj"><b>experiments</b></a>and <a href="https://goo.gl/ac2Qji"><b>modeling!</b></a></h4> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| Line 176: | Line 188: | ||

<source src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/a/a8/T--TAS_Taipei--Oscar_Vid.mp4" type="video/mp4"> Your browser does not support the video tag. | <source src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/a/a8/T--TAS_Taipei--Oscar_Vid.mp4" type="video/mp4"> Your browser does not support the video tag. | ||

</video> | </video> | ||

| − | </div> | + | </div><br> |

| − | <div class="row" id=" | + | <div class="row" id="PRApply"> |

| − | <h1 class="section-title col-lg-12"> | + | <h1 class="section-title col-lg-12">Applying PR in a WWTP Model</h1> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <h4 class="para col-lg- | + | <h4 class="para col-lg-8"> After we experimentally demonstrated that PR binds to CC-NPs, we wanted to <b>test PR bacteria under conditions similar to a WWTP aeration tank</b>. To learn more about those specific conditions, we visited and talked to engineers at Dihua WWTP, our local urban facility. At Dihua, wastewater is retained in aeration tanks for <b>up to 5 hours</b>, and a <b>central rotor constantly churns the wastewater</b>. To simulate these conditions, we built our own “aeration tank” using clear cylinders and a central rotor. Then, we set up three groups in separate aeration tanks: PR <i>E. coli</i> + distilled water, PR <i>E. coli</i> + CC-AgNP, or CC-AgNP solution alone (figure 5-4A). Finally, we turned on the rotor and churned the mixture for 5 hours. <br><br> |

| − | </div> | + | In WWTPs, aeration tanks lead to secondary sedimentation tanks (figure 5-2), where flocculants—polymers that aggregate suspended solids—are added to accelerate sedimentation. During our visit to Dihua WWTP, the engineers gave us samples of their flocculants. After 5 hours of mixing, we stopped the rotor and added the flocculant powder used by Dihua WWTP to each tank (video 5-1). In the CC-AgNP cylinder, adding flocculants did not have any effect (figure 5-4B and C), suggesting that <b>current wastewater treatment practices cannot remove NPs</b>. In the cylinders containing PR bacteria, however, aggregated materials (including bacteria) settled to the bottom of the cylinder as expected (figure 5-4B). We then centrifuged the contents of each cylinder, and observed that the pellet of the PR bacteria + CC-AgNPs mixture was orange, reflecting the presence of aggregated CC-AgNPs (figure 5-4C). <b>In this WWTP aeration tank simulation, we show that PR bacteria pulls down CC-AgNPs</b>. </h4> |

| + | <div class="image_container col-lg-4"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/a/a3/T--TAS_Taipei--PR_prototype_exp.jpg" alt="test" id="group"> | ||

| + | <h4 class="subtitle"><b>Figure 5-4 Applying PR in a WWTP model.</b> A) Three groups were setup and churned for 5 hours: PR bacteria + distilled water, PR bacteria + CC-AgNPs, and CC-AgNPs + distilled water. B) After 5 hours, flocculants were added and aggregated materials settled to the bottom. C) We then centrifuged the contents of each cylinder, and observed that the pellet of the PR bacteria + CC-AgNPs mixture was orange, reflecting the presence of aggregated CC-AgNPs. <span class="subCred">Experiment & Figure: Justin Y.</span></h4> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | </div><br> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="image_container col-lg- | + | <div class="image_container col-lg-10 col-lg-offset-1"> |

| − | + | <video controls="" class="col-lg-12"> | |

| − | + | <source src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/1/13/T--TAS_Taipei--PR_Video.mp4" type="video/mp4"> Your browser does not support the video | |

| − | + | </video> | |

| − | + | <h4 class="subtitle"><b> Video 5-1 Testing PR bacteria in simulated aeration tanks.</b> Three tanks were setup: PR <i>E. coli</i> + distilled water (right), PR <i>E. coli</i> + CC-AgNP (middle), or CC-AgNP solution alone (left). The contents were mixed for 5 hours to simulate the conditions in an aeration tank. Then, we stopped the rotor and added the flocculant powder used by Dihua WWTP to each tank. In the CC-AgNP cylinder, adding flocculants did not have any effect, suggesting that current wastewater treatment practices cannot remove NPs. In the cylinders containing PR bacteria, however, aggregated materials (including bacteria) settled to the bottom of the cylinder as expected. We observed that the aggregated PR bacteria + CC-AgNPs mixture was orange, indicating the presence of CC-AgNPs. <span class="subCred">Experiment & Video: Justin Y.</span></h4> | |

| − | </div> | + | </div> |

| − | <div class="row" id=" | + | </div><br> |

| − | <h1 class=" | + | <div class="row" id="biofilm"> |

| + | <h1 class="title2 col-lg-12">BIOFILM CONSIDERATIONS</h1> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <h4 class="para col-lg- | + | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> To achieve our goal of applying biofilms in WWTPs, we need to inform WWTP managers on the amount of biofilm necessary to trap their desired amount of NPs. Thus, we devised two experiments to investigate the effect of 1) biofilm volume and 2) biofilm surface area on NP trapping; the results of these experiments were incorporated into our model. (Learn more about modeling <a href="https://2017.igem.org/Team:TAS_Taipei/Model">here</a>!) |

| − | + | </h4> | |

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | <div class="row" id=" | + | <div class="row" id="volume"> |

| − | <h1 class="section-title col-lg-12"> | + | <h1 class="section-title col-lg-12">Volume Does Not Affect NP Trapping</h1> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <h4 class="para col-lg- | + | <h4 class="para col-lg-7"> To test the effects of biofilm volume, <i>E. coli</i> biofilms were grown, extracted, and washed as described in the <a href="https://goo.gl/Q69wZS">Experimental</a> page. These tests were performed with Gold NPs (AuNPs). Because AuNP solution is purple in color, we can take absorbance measurements and convert these values to AuNP concentration using a standard curve (figure 5-5A). 10 mL of AuNP solution was added to different volumes of biofilm (figure 5-5B). The containers were shaken at 100 rpm overnight to maximize interaction between the biofilm and AuNPs. Finally, the mixtures were transferred to conical tubes and centrifuged to isolate the supernatant, which contains free AuNPs quantifiable using a spectrophotometer set at 527 nm. <br><br> |

| − | + | Adding more than 1 mL of biofilm to the same amount of AuNP solution did not trap more AuNPs (figure 5-5C). We observed that 1 mL of biofilm was just enough to fully cover the bottom of the container. Since only the top of the biofilm directly contacted the AuNP solution, increasing biofilm volume beyond 1 mL simply increased the depth and not the contact area between biofilm and AuNPs. Therefore, <b>we concluded that biofilm volume is not a main factor determining NP removal. </b> | |

| − | + | </h4> | |

| − | + | <div class="image_container col-lg-5"> | |

| − | + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/8/89/T--TAS_Taipei--Volume_trial-min.jpg" alt="test" id="group"> | |

| − | + | <h4 class="subtitle"><b>Figure 5-5 Biofilm volume does not affect NP trapping. </b> A) AuNP standard curve relates absorbance and molar concentration. B) Different amounts of biofilm were added to same amount of AuNP solution. C) Increasing biofilm volume beyond 1 mL does not increase NP removal. <span class="subCred">Experiment: Yvonne W.</span></h4> | |

| − | <div class="image_container col-lg-5 | + | |

| − | <h4 class="subtitle"> | + | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | </div> | + | </div><br> |

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> | + | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> |

| + | </h4> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | + | <div class="row" id="SA"> | |

| − | + | <h1 class="section-title col-lg-12">Surface Area Affects NP Trapping</h1> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | <div class="row" id=" | + | |

| − | <h1 class="section-title col-lg-12"> | + | |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <h4 class="para col-lg- | + | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> Next, we tested the effects of surface area on NP removal. Similar to the previous experiment, biofilms were extracted and washed. Two experimental groups were set up in different sized cylinders, with either a small (~1.5 cm<sup>2</sup>) or big (~9 cm<sup>2</sup>) base area (figure 5-6A). The bottom 0.5 cm of each container was covered by biofilm, then 10 mL of AuNP solution was added. In this case, the depth of biofilm is consistent, so the contact area between AuNPs and biofilm is equal to the area of the container’s base. All containers were shaken at 100 rpm at room temperature. Every hour (for a total of five hours), one replicate from each group was centrifuged and the absorbance of free AuNPs in the supernatant was measured at 527 nm. |

| − | + | </h4> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | </ | + | |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="image_container col-lg- | + | <div class="image_container col-lg-10 col-lg-offset-1"> <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/5/50/T--TAS_Taipei--SA_new.jpg" alt="test" id="group"> |

| − | + | <h4 class="subtitle"><b>Figure 5-6 Increasing NP-biofilm contact area increases NP removal. </b> A) Different sized cylinders were used to change NP-biofilm contact area. B) AuNPs were trapped much faster in the large container with a greater biofilm surface area. <span class="subCred">Experiment: Justin P., Florence L., Yvonne W.</span></h4> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | <h4 class="subtitle"><b>Figure | + | |

</div> | </div> | ||

</div><br> | </div><br> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> | + | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> We observed that <b>AuNPs were trapped much faster in the large container with a greater biofilm surface area</b> (figure 5-6B). This experiment informed our modeling team that the surface area of biofilm is the main factor that affects NP removal. (Learn more about it <a href="https://2017.igem.org/Team:TAS_Taipei/Model">here!</a>)</h4> |

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | <div class="row" id=" | + | <div class="row" id="prototype"> |

| − | <h1 class=" | + | <h1 class="title2 col-lg-12">BIOFILM PROTOTYPE</h1> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> | + | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> <b>Our goal is to design a prototype that 1) maximizes the contact area between biofilm and NPs, and 2) can be easily implemented in existing WWTP infrastructure. </b> </h4> |

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | <div class="row" id=" | + | <div class="row" id="max"> |

| − | + | <h1 class="section-title col-lg-12">Maximize NP-Biofilm Contact Area</h1> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | <h1 class="section-title col-lg-12"> | + | |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> | + | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> Some aquariums already utilize biofilms grown on plastic structures called <i>biocarriers</i> for water purification. Commercial biocarriers use various ridges, blades, and hollow structures to maximize surface area available for biofilm attachment (figure 5-7A). With that in mind, we <b> designed and 3D-printed plastic (polylactic acid, or PLA) prototypes with many radiating blades to maximize the area available for biofilm attachment</b> (figure 5-7B). We used PLA because it was readily available for printing and easy to work with, allowing us to quickly transition from constructing to testing our prototype. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

</h4> | </h4> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <div class="image_container col-lg- | + | <div class="image_container col-lg-8 col-lg-offset-2"> <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/d/db/T--TAS_Taipei--biocarriers.jpg" alt="test" id="group"> |

| − | <h4 class="subtitle"><b> | + | <h4 class="subtitle"><b>Figure 5-7 Biocarriers enable biofilm attachment. </b> A) An example of commercial biocarriers. B) We 3D-printed our prototype to maximize surface area for biofilm attachment. C) We observed biofilms loosely attached onto our prototype. <span class="subCred">Prototype: Candice L., Yvonne W. Experiment: Yvonne W.</span></h4> |

</div> | </div> | ||

</div><br> | </div><br> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> | + | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> To test how well biofilms actually adhere and develop on our prototypes, we used BBa_K2229300 liquid cultures, since they produced the most biofilm in previous tests. After an incubation period, <b>we observed biofilm growth and attachment to our prototypes</b> (figure 5-7C). |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

</h4> | </h4> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | <div class="row" id="infra"> | |

| − | + | <h1 class="section-title col-lg-12">Maximize Adaptability to Existing Infrastructure</h1> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | <div class="row" id=" | + | |

| − | <h1 class="section-title col-lg-12"> | + | |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> We | + | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> <b>We would like to implement our prototype in secondary sedimentation tanks in existing WWTPs.</b> The water in this step is relatively calm compared to aeration tanks, which will help keep biofilm structures intact. In addition, larger particles in wastewater would already be filtered out, which maximizes NP removal. The director of Boswell’s WWTP told us that most sedimentation tanks use devices called surface skimmers, which constantly rotate around a central axle, to remove oils; we envision attaching our prototype to the same central axle. In WWTPs that do not have a central rotor in the sedimentation tank, a motor and rod could be easily installed. The slow rotation would keep biofilm structure intact while at the same time, increase the amount of NPs that come into contact with our biofilm. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

</h4> | </h4> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | <div class="row"> | + | <div class="row" id="WWTPModel"> |

| − | < | + | <h1 class="section-title col-lg-12">Applying Biofilm in a WWTP Model</h1> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | < | + | <h4 class="para col-lg-7"> After we experimentally demonstrated that biofilms trap NPs, we wanted to <b>test biofilms under conditions similar to a WWTP sedimentation tank</b>. Based on Boswell’s circular tank design, we built our own “sedimentation tanks” using clear plastic tubes, and attached biocarriers to a central spinning rotor. Three cylinders were set up: biofilm + distilled water, biofilm + AuNP, and AuNP solution alone. Here, we decided to grow biofilm directly onto biocarriers in the cylinders to minimize any disturbances. Finally, we turned on the rotor—set at a slow rotation speed—to simulate the mild movement of water in sedimentation tanks. <br><br> |

| − | + | In this simulation, we expected to see biofilms first attach and grow on the biocarriers, and then begin trapping NPs in the tanks. After about 30 hours of mixing, <b>the color of the AuNP solution started to change from purple to clear in the cylinder containing biofilm</b> (figure 5-8). This suggested that enough biofilm had adhered onto the biocarrier and began removing AuNPs in the solution. In contrast, the cylinder containing only AuNP solution did not change at all (video 5-2). As the biofilm-coated biocarrier removed AuNPs from solution, we also observed more purple aggregates of AuNP sticking to the rotating biofilm biocarrier. Here, <b>we have demonstrated that our biofilm approach effectively removes NPs in a WWTP sedimentation tank model</b>. | |

| − | + | </h4> | |

| − | + | <div class="image_container col-lg-5"> <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/1/16/T--TAS_Taipei--Biofilm_vid_fig.jpg" alt="test" id="group"> | |

| − | + | <h4 class="subtitle"><b>Figure 5-8 Biofilms effectively remove NPs in a simulated sedimentation tank. </b> After about 30 hours of mixing, the color of the AuNP solution started to change from purple to clear (blue asterisk) in the cylinder containing biofilm. <span class="subCred">Prototype & Experiment: Yvonne W., Justin Y. | |

| − | + | </span></h4> | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | < | + | |

| − | <div class="image_container col-lg-5"> <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/ | + | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | + | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</div><br> | </div><br> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | + | <div class="image_container col-lg-10 col-lg-offset-1"> | |

| − | + | <video controls="" class="col-lg-12"> | |

| − | + | <source src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/7/75/T--TAS_Taipei--Biofilm_Video.mp4" type="video/mp4"> Your browser does not support the video tag. | |

| − | + | </video> | |

| − | + | <h4 class="subtitle"><b> Video 5-2 Testing biofilm in simulated sedimentation tanks.</b> Based on Boswell’s circular tank design, we built our own “sedimentation tanks” using clear plastic tubes, and attached biocarriers to a central spinning rotor. Three tanks were set up: biofilm + distilled water (right), biofilm + AuNP (middle), and AuNP solution alone (left). After about 30 hours of mixing, the color of the AuNP solution started to change from purple to clear in the cylinder containing biofilm. In contrast, the cylinder containing only AuNP solution did not change at all. Timelapse video shows the tanks 36 hours after the start. <span class="subCred">Experiment & Video: Yvonne W.</span></h4> | |

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</div><br> | </div><br> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> | + | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> *Details on any experimental setup can be found in the Prototype and Modeling sections of our <a href="https://2017.igem.org/Team:TAS_Taipei/Notebook">lab notebook.</a> |

| + | </h4> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row" id="ref"> | <div class="row" id="ref"> | ||

| Line 453: | Line 308: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> | + | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> Davis, Peter S. “The Biological Basis of Wastewater Treatment.” s-Can.nl, 2005, www.s-can.nl/media/1000154/thebiologicalbasisofwastewatertreatment.pdf.<br><br> |

| + | Fattahi, S., Kafil, H. S., Nahai, M. R., Asgharzadeh, M., Nori, R., & Aghazadeh, M. (2015). Relationship of biofilm formation and different virulence genes in uropathogenic Escherichia coli isolates from Northwest Iran. GMS Hygiene and Infection Control, 10, Doc11. http://doi.org/10.3205/dgkh000254<br><br> | ||

| + | Mueller, N. C., & Nowack, B. (2008). Exposure Modeling of Engineered Nanoparticles in the Environment. Environmental Science & Technology, 42(12), 4447-4453. doi:10.1021/es7029637 | ||

| + | <br><br> | ||

| + | Malik, O. (2014, January 22). Primary vs. Secondary: Types of Wastewater Treatment. Retrieved October 12, 2017, from http://archive.epi.yale.edu/case-study/primary-vs-secondary-types-wastewater-treatment<br><br> | ||

| + | Pescod, M. (1992). Wastewater treatment and use in agriculture (Vol. 47). Rome: United Nations. | ||

| + | Vert, M., Doi, Y., Hellwich, K., et al. (2012). Terminology for biorelated polymers and applications (IUPAC Recommendations 2012). Pure and Applied Chemistry, 84(2), pp. 377-410. Retrieved 9 Oct. 2017, from doi:10.1351/PAC-REC-10-12-04 | ||

| + | </h4> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<script> | <script> | ||

$("a").on('click', function(event) { | $("a").on('click', function(event) { | ||

| Line 648: | Line 505: | ||

}); | }); | ||

}) | }) | ||

| − | |||

</script> | </script> | ||

</body> | </body> | ||

</html> | </html> | ||

Latest revision as of 03:47, 3 December 2017

X

Project

Experiments

Modeling

Prototype

Human Practices

Safety

About Us

Attributions

Project

Experiment

Modeling

Prototype

Human Practice

Safety

About Us

Attributions

PROTOTYPE

It is estimated that about 95% of nanoparticles (NPs) used in consumer products end up in wastewater (Mueller & Nowack. 2008). Our goal is to apply our biofilm and Proteorhodopsin (PR) bacteria in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) to remove most NPs before the effluent is released into the environment.

WASTEWATER TREATMENT

What is the process?

Figure 5-1 Typical wastewater treatment process. Figure: Yvonne W.

When wastewater enters a plant, the first step is to remove coarse solids and large materials using a grit screen (figure 5-1). The water can then be processed in three main stages: Primary, Secondary, and sometimes Tertiary Treatment (Pescod 1992). In Primary Treatment, heavy solids are removed by sedimentation while floating materials (such as oils) can be taken out by skimming. However, dissolved materials and colloids—small, evenly dispersed solids such as NPs—are not removed here (Pescod 1992). Secondary Treatment generally involves the use of aeration tanks, where aerobic microbes help to break down organic materials. This is also known as the activated sludge process (Davis 2005). In a subsequent sedimentation step, the microbes are removed and the effluent is disinfected (often by chlorine or UV) before it is released into the environment. In certain WWTPs, wastewater may go through Tertiary Treatment, an advanced process typically aimed to remove nitrogen and phosphorous, and assumed to produce an effluent free of viruses (Pescod 1992). However, Tertiary Treatment requires additional infrastructure that is expensive and complex, limiting its global usage (Pescod 1992; Malik 2014).

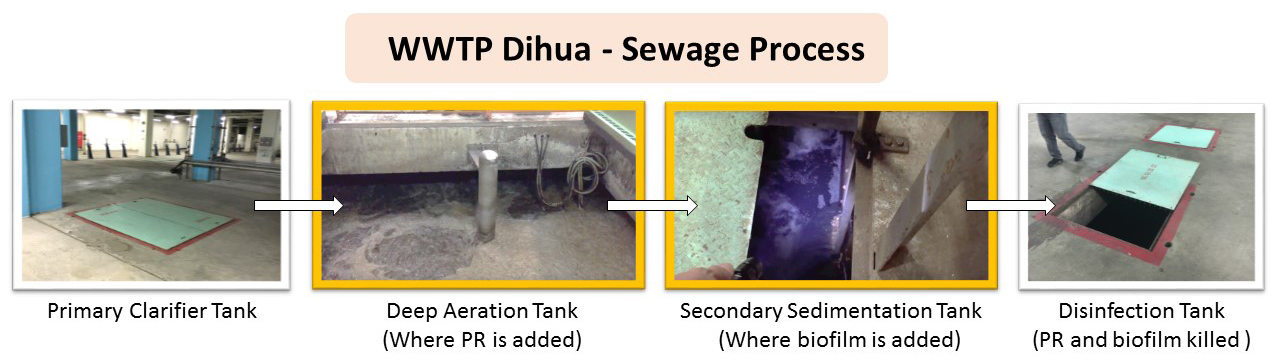

Ideally, we would like to remove NPs from all systems, so we visited two different types of WWTPs: a local urban facility in Dihua, Taipei, and a smaller rural facility in Boswell, Pennsylvania. We found that wastewater in the two plants is treated using very similar processes (figures 5-2 and 5-3). We also contacted Thomas J. Brown, the Water Program Specialist of the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, and asked him if there were differences between rural and urban plants that we should consider when thinking about implementing our project. He responded, “[t]he heart of the treatment process is the biological process used for treatment; the biology remains the same regardless of facility size.” Thus, in both types of WWTPs, we want to apply our engineered bacteria in the Secondary Treatment step—either in aeration tanks or in the sedimentation tank.

Figure 5-2 Dihua WWTP sewage process. Figure: Christine C.

Figure 5-3 Boswell WWTP sewage process. Figure: Christine C.

Biosafety

We used a safe and common lab strain of E. coli, K-12, as our chassis (Environmental Protection Agency 1977). In both approaches, our constructs do not express proteins associated with virulence: PR is a transmembrane protein that commonly exists in marine bacteria, and for biofilm production we were careful to avoid known virulence factors such as alpha hemolysins (Fattahi et al. 2015). Most importantly, biosafety is built into WWTPs. Before treated effluent is released back into the environment, it must go through a final disinfection step, where chlorine, ozone, or UV radiation are used to kill microbes still present in the wastewater (Pescod 1992).

PR CONSIDERATIONS

During our visit to Dihua WWTP, the chief engineer informed us that they use the activated sludge process, which uses aerobic microbes to digest organic matter in aeration tanks. The steady influx and mixing of air provide oxygen favorable to aerobic microbes; the turbulent water also increases the probability of PR binding to citrate-capped NPs (CC-NPs). Thus, we envision directly adding PR E. coli into existing aeration tanks. In addition, as part of the activated sludge process, WWTPs regularly cycle microbe-rich sludge back into aeration tanks to maintain the microbial population (figure 5-1). Ideally, this would stabilize the PR bacterial population in aeration tanks, allowing this system to be low-maintenance and easily adaptable to existing infrastructure.

To facilitate the application of PR bacteria in WWTPs, our modeling team created a calculator that informs WWTP managers the amount of PR bacteria they need to trap their desired amount of CC-NPs based on our experimental results and the conditions of their WWTP. Learn more about PR experimentsand modeling!

Applying PR in a WWTP Model

After we experimentally demonstrated that PR binds to CC-NPs, we wanted to test PR bacteria under conditions similar to a WWTP aeration tank. To learn more about those specific conditions, we visited and talked to engineers at Dihua WWTP, our local urban facility. At Dihua, wastewater is retained in aeration tanks for up to 5 hours, and a central rotor constantly churns the wastewater. To simulate these conditions, we built our own “aeration tank” using clear cylinders and a central rotor. Then, we set up three groups in separate aeration tanks: PR E. coli + distilled water, PR E. coli + CC-AgNP, or CC-AgNP solution alone (figure 5-4A). Finally, we turned on the rotor and churned the mixture for 5 hours.

In WWTPs, aeration tanks lead to secondary sedimentation tanks (figure 5-2), where flocculants—polymers that aggregate suspended solids—are added to accelerate sedimentation. During our visit to Dihua WWTP, the engineers gave us samples of their flocculants. After 5 hours of mixing, we stopped the rotor and added the flocculant powder used by Dihua WWTP to each tank (video 5-1). In the CC-AgNP cylinder, adding flocculants did not have any effect (figure 5-4B and C), suggesting that current wastewater treatment practices cannot remove NPs. In the cylinders containing PR bacteria, however, aggregated materials (including bacteria) settled to the bottom of the cylinder as expected (figure 5-4B). We then centrifuged the contents of each cylinder, and observed that the pellet of the PR bacteria + CC-AgNPs mixture was orange, reflecting the presence of aggregated CC-AgNPs (figure 5-4C). In this WWTP aeration tank simulation, we show that PR bacteria pulls down CC-AgNPs.

Figure 5-4 Applying PR in a WWTP model. A) Three groups were setup and churned for 5 hours: PR bacteria + distilled water, PR bacteria + CC-AgNPs, and CC-AgNPs + distilled water. B) After 5 hours, flocculants were added and aggregated materials settled to the bottom. C) We then centrifuged the contents of each cylinder, and observed that the pellet of the PR bacteria + CC-AgNPs mixture was orange, reflecting the presence of aggregated CC-AgNPs. Experiment & Figure: Justin Y.

Video 5-1 Testing PR bacteria in simulated aeration tanks. Three tanks were setup: PR E. coli + distilled water (right), PR E. coli + CC-AgNP (middle), or CC-AgNP solution alone (left). The contents were mixed for 5 hours to simulate the conditions in an aeration tank. Then, we stopped the rotor and added the flocculant powder used by Dihua WWTP to each tank. In the CC-AgNP cylinder, adding flocculants did not have any effect, suggesting that current wastewater treatment practices cannot remove NPs. In the cylinders containing PR bacteria, however, aggregated materials (including bacteria) settled to the bottom of the cylinder as expected. We observed that the aggregated PR bacteria + CC-AgNPs mixture was orange, indicating the presence of CC-AgNPs. Experiment & Video: Justin Y.

BIOFILM CONSIDERATIONS

To achieve our goal of applying biofilms in WWTPs, we need to inform WWTP managers on the amount of biofilm necessary to trap their desired amount of NPs. Thus, we devised two experiments to investigate the effect of 1) biofilm volume and 2) biofilm surface area on NP trapping; the results of these experiments were incorporated into our model. (Learn more about modeling here!)

Volume Does Not Affect NP Trapping

To test the effects of biofilm volume, E. coli biofilms were grown, extracted, and washed as described in the Experimental page. These tests were performed with Gold NPs (AuNPs). Because AuNP solution is purple in color, we can take absorbance measurements and convert these values to AuNP concentration using a standard curve (figure 5-5A). 10 mL of AuNP solution was added to different volumes of biofilm (figure 5-5B). The containers were shaken at 100 rpm overnight to maximize interaction between the biofilm and AuNPs. Finally, the mixtures were transferred to conical tubes and centrifuged to isolate the supernatant, which contains free AuNPs quantifiable using a spectrophotometer set at 527 nm.

Adding more than 1 mL of biofilm to the same amount of AuNP solution did not trap more AuNPs (figure 5-5C). We observed that 1 mL of biofilm was just enough to fully cover the bottom of the container. Since only the top of the biofilm directly contacted the AuNP solution, increasing biofilm volume beyond 1 mL simply increased the depth and not the contact area between biofilm and AuNPs. Therefore, we concluded that biofilm volume is not a main factor determining NP removal.

Figure 5-5 Biofilm volume does not affect NP trapping. A) AuNP standard curve relates absorbance and molar concentration. B) Different amounts of biofilm were added to same amount of AuNP solution. C) Increasing biofilm volume beyond 1 mL does not increase NP removal. Experiment: Yvonne W.

Surface Area Affects NP Trapping

Next, we tested the effects of surface area on NP removal. Similar to the previous experiment, biofilms were extracted and washed. Two experimental groups were set up in different sized cylinders, with either a small (~1.5 cm2) or big (~9 cm2) base area (figure 5-6A). The bottom 0.5 cm of each container was covered by biofilm, then 10 mL of AuNP solution was added. In this case, the depth of biofilm is consistent, so the contact area between AuNPs and biofilm is equal to the area of the container’s base. All containers were shaken at 100 rpm at room temperature. Every hour (for a total of five hours), one replicate from each group was centrifuged and the absorbance of free AuNPs in the supernatant was measured at 527 nm.

Figure 5-6 Increasing NP-biofilm contact area increases NP removal. A) Different sized cylinders were used to change NP-biofilm contact area. B) AuNPs were trapped much faster in the large container with a greater biofilm surface area. Experiment: Justin P., Florence L., Yvonne W.

We observed that AuNPs were trapped much faster in the large container with a greater biofilm surface area (figure 5-6B). This experiment informed our modeling team that the surface area of biofilm is the main factor that affects NP removal. (Learn more about it here!)

BIOFILM PROTOTYPE

Our goal is to design a prototype that 1) maximizes the contact area between biofilm and NPs, and 2) can be easily implemented in existing WWTP infrastructure.

Maximize NP-Biofilm Contact Area

Some aquariums already utilize biofilms grown on plastic structures called biocarriers for water purification. Commercial biocarriers use various ridges, blades, and hollow structures to maximize surface area available for biofilm attachment (figure 5-7A). With that in mind, we designed and 3D-printed plastic (polylactic acid, or PLA) prototypes with many radiating blades to maximize the area available for biofilm attachment (figure 5-7B). We used PLA because it was readily available for printing and easy to work with, allowing us to quickly transition from constructing to testing our prototype.

Figure 5-7 Biocarriers enable biofilm attachment. A) An example of commercial biocarriers. B) We 3D-printed our prototype to maximize surface area for biofilm attachment. C) We observed biofilms loosely attached onto our prototype. Prototype: Candice L., Yvonne W. Experiment: Yvonne W.

To test how well biofilms actually adhere and develop on our prototypes, we used BBa_K2229300 liquid cultures, since they produced the most biofilm in previous tests. After an incubation period, we observed biofilm growth and attachment to our prototypes (figure 5-7C).

Maximize Adaptability to Existing Infrastructure

We would like to implement our prototype in secondary sedimentation tanks in existing WWTPs. The water in this step is relatively calm compared to aeration tanks, which will help keep biofilm structures intact. In addition, larger particles in wastewater would already be filtered out, which maximizes NP removal. The director of Boswell’s WWTP told us that most sedimentation tanks use devices called surface skimmers, which constantly rotate around a central axle, to remove oils; we envision attaching our prototype to the same central axle. In WWTPs that do not have a central rotor in the sedimentation tank, a motor and rod could be easily installed. The slow rotation would keep biofilm structure intact while at the same time, increase the amount of NPs that come into contact with our biofilm.

Applying Biofilm in a WWTP Model

After we experimentally demonstrated that biofilms trap NPs, we wanted to test biofilms under conditions similar to a WWTP sedimentation tank. Based on Boswell’s circular tank design, we built our own “sedimentation tanks” using clear plastic tubes, and attached biocarriers to a central spinning rotor. Three cylinders were set up: biofilm + distilled water, biofilm + AuNP, and AuNP solution alone. Here, we decided to grow biofilm directly onto biocarriers in the cylinders to minimize any disturbances. Finally, we turned on the rotor—set at a slow rotation speed—to simulate the mild movement of water in sedimentation tanks.

In this simulation, we expected to see biofilms first attach and grow on the biocarriers, and then begin trapping NPs in the tanks. After about 30 hours of mixing, the color of the AuNP solution started to change from purple to clear in the cylinder containing biofilm (figure 5-8). This suggested that enough biofilm had adhered onto the biocarrier and began removing AuNPs in the solution. In contrast, the cylinder containing only AuNP solution did not change at all (video 5-2). As the biofilm-coated biocarrier removed AuNPs from solution, we also observed more purple aggregates of AuNP sticking to the rotating biofilm biocarrier. Here, we have demonstrated that our biofilm approach effectively removes NPs in a WWTP sedimentation tank model.