| Line 262: | Line 262: | ||

<source src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/4/4b/T--TAS_Taipei--Final_Video.mp4" type="video/mp4"> Your browser does not support the video tag. | <source src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/4/4b/T--TAS_Taipei--Final_Video.mp4" type="video/mp4"> Your browser does not support the video tag. | ||

</video> | </video> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="row" id="symposium"> | ||

| + | <h1 class="section-title col-lg-12">Research Symposium -- Poster and Oral Presentations</h1> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> | ||

| + | At TAS we conduct research symposiums twice a year to showcase the research of students who take a variety of research courses. Before we decided our project topic, we developed 4 different project ideas to present at our first research symposium (poster session). We received feedback from both students and teachers, then decided on our current project. At our second research symposium, we presented on our current project, Nanotrap! (Presenters: Candice L., William C., Chansie Y., Christine C., Yvonne, W., Justin Y., Dylan L., and Catherine Y.) | ||

| + | </h4> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

| + | <div class="row"> | ||

| + | <div class="image_container_big col-lg-8 col-lg-offset-2"> | ||

| + | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/c/c3/T--TAS_Taipei--Symposium-min.jpg" alt="test" id="group"> | ||

| + | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row" id="bioethics"> | <div class="row" id="bioethics"> | ||

| Line 299: | Line 312: | ||

<div class="image_container col-lg-10 col-lg-offset-1"> | <div class="image_container col-lg-10 col-lg-offset-1"> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/9/97/T--TAS_Taipei--general_questionsPic.JPG" alt="test" id="group"> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/9/97/T--TAS_Taipei--general_questionsPic.JPG" alt="test" id="group"> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

Revision as of 08:36, 18 October 2017

X

Project

Experiments

Modeling

Prototype

Human Practices

Safety

About Us

Attributions

Project

Experiment

Modeling

Prototype

Human Practice

Biosafety

About Us

Attributions

hi

ENGAGEMENT AND EDUCATION

Two goals for our human practices were to introduce synthetic biology to grade school students and to raise awareness about nanoparticles usage and pollution. We taught kindergarteners basic science and how to use their observational skills through a series of experiments. We also introduced 7th graders to synthetic biology theory and experiments. To raise awareness, we held an interactive bioethics panel where students interacted with team members to learn about nanoparticles. Furthermore, we spent many hours in our city conducting surveys and handing out fliers that contained information about nanoparticles. We were even able to fundraise over $500 USD for a two charities. Finally, we created a policy brief about some of the current issues of nanoparticle regulation and sent it to government officials and news agencies. The Minister of the Taiwan Environmental Protection Agency even said they would consider our brief in future policy regulations.

Kindergarten -- Observing the “invisible”

Our iGEM team hosted over 120 kindergarten students to teach them the power of observation and the basics of science. For example, we taught them how to use microscopes to look at anti-counterfeiting measures on paper money and how to use refraction lenses to see that white light is made up of various colors. (Whole Team activity)

7th Grade Introduction to Synthetic Biology

We introduced iGEM and the basics of synthetic biology to all 200+ students in the seventh grade. They learned how to use micropipettes, as well as how to load and run dyes through an agarose gel. We also gave students different real world problems. Using paper biobrick parts, students put together constructs that would solve the given problems. (Whole Team activity)

Spring Fair -- Spreading Public Awareness of Nanoparticles

At our school’s annual spring fair, we manned a booth where people could create their own glitter slime by mixing polyvinyl alcohol and sodium borate solutions. The slime was meant to simulate the biofilm we use to trap nanoparticles (in this demo, glitter) in wastewater treatment plants. We also showed a few SEM images of bacteria, as well as everyday products that contain nanoparticles such as toothpaste and sunscreen. Everyone who came by our booth was encouraged to take our survey so we could record opinions on bioethics and concerns about nanoparticles. (Whole team activity)

iGEM Slime booth at Spring Fair along with the iPad surveys set up next to the tables.

SEM images that show nanoparticles in daily products (ex: toothpaste and sunscreen)

Bioethics Panel

We hosted a Bioethics Panel, where we invited students and teachers to discuss the moral, social and environmental concerns of our project. To encourage participants to consider the problems from multiple perspectives, we created a role-playing game and assigned different roles to participants. We then asked for their opinions on nanoparticle usage and disposal from the perspective of their assigned role. (Whole team activity)

For instance, one of our questions was:

“Dihua WWTP has no nanoparticle removal plan. Should this be the job of the wastewater plant? Or the nanoparticle manufacturer?”

The following roles were assigned:

- Wastewater plant manager

- Nanoparticle manufacturer

- Citizen

- Fisherman

- Fish

Most of the wastewater plant managers thought that nanoparticle manufacturers should be responsible for removing nanoparticles, because they have more information (e.g., solubility, toxicity, etc.) about their own products. However, many other participants were skeptical that manufacturers could be trusted to remove their own contamination and agreed that WWTPs should ultimately be responsible for cleaning water contaminated with nanoparticles.

This activity gave us great insight on how the public perceives nanoparticle usage and regulation in society. This also gave us a chance to talk to people about both the benefits and the dangers of using nanoparticles.

Public Outreach -- A Tour of Taipei

Some members of the iGEM team went to various popular sites in Taipei to pass out fliers and conduct surveys. We visited National Taiwan University, Chiang Kai-Shek Memorial Hall, and Taipei 101. This helped us collect feedback from different age groups and backgrounds. This was a great and fun way to spread awareness of nanoparticle pollution! (Team members: Ashley L., Emily C., Florence L., Candice L., Yvonne W., Justin Y., Avery W., Christine C., Jesse K., and Laurent H.)

Here's a video we made for this event.

Research Symposium -- Poster and Oral Presentations

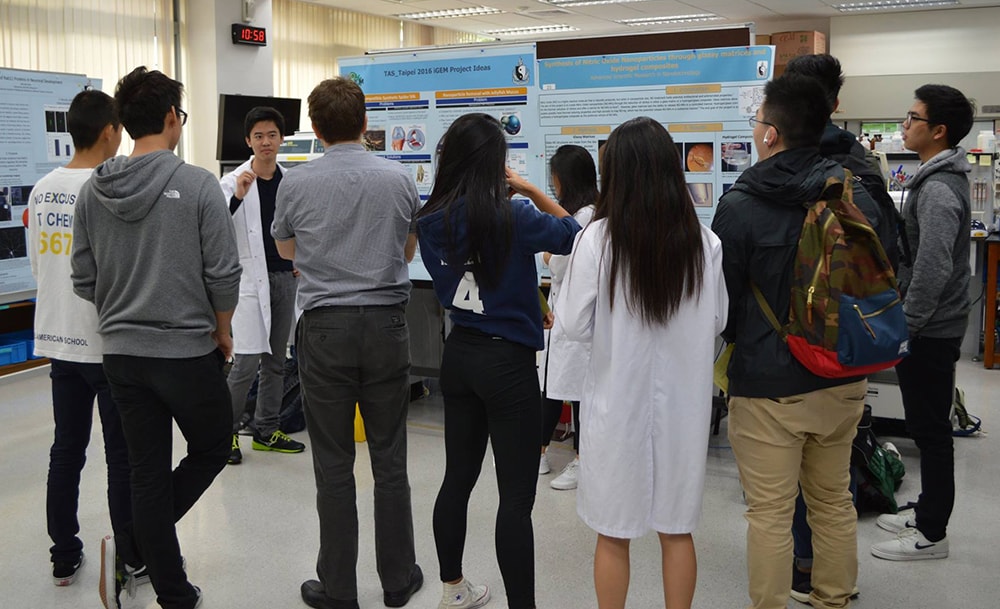

At TAS we conduct research symposiums twice a year to showcase the research of students who take a variety of research courses. Before we decided our project topic, we developed 4 different project ideas to present at our first research symposium (poster session). We received feedback from both students and teachers, then decided on our current project. At our second research symposium, we presented on our current project, Nanotrap! (Presenters: Candice L., William C., Chansie Y., Christine C., Yvonne, W., Justin Y., Dylan L., and Catherine Y.)

Bioethics Panel

We hosted a Bioethics Panel, where we invited students and teachers to discuss the moral, social and environmental concerns of our project. To encourage participants to consider the problems from multiple perspectives, we created a role-playing game and assigned different roles to participants. We then asked for their opinions on nanoparticle usage and disposal from the perspective of their assigned role. (Whole team activity)

For instance, one of our questions was:

“Dihua WWTP has no nanoparticle removal plan. Should this be the job of the wastewater plant? Or the nanoparticle manufacturer?”

The following roles were assigned:

- Wastewater plant manager

- Nanoparticle manufacturer

- Citizen

- Fisherman

- Fish

Most of the wastewater plant managers thought that nanoparticle manufacturers should be responsible for removing nanoparticles, because they have more information (e.g., solubility, toxicity, etc.) about their own products. However, many other participants were skeptical that manufacturers could be trusted to remove their own contamination and agreed that WWTPs should ultimately be responsible for cleaning water contaminated with nanoparticles.

This activity gave us great insight on how the public perceives nanoparticle usage and regulation in society. This also gave us a chance to talk to people about both the benefits and the dangers of using nanoparticles.

5th Annual Asia-Pacific iGEM Conference -- NCTU

In preparation for the Giant Jamboree, we attended the 5th annual Asia-Pacific iGEM conference at NCTU to share and receive valuable feedback from other college and high school teams in Taiwan. This event allowed us to consider different aspects of our project using feedback from other teams. (Presenters: William C., Yvonne W., and Justin Y.)

Policy Brief -- Nanoparticle Regulation Issues and Case Studies

Our team has conducted extensive research on existing regulatory laws and policies regarding nanoparticles and nanomaterials. We have investigated chemical regulations, including the Restriction, Evaluation, Authorization, and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH), A Toxic Substances Control Act (TCSA), CLP, and the Clean Air Act (CAA). There are significant obstacles to successfully regulating nanoparticles, such as conflicting definitions on nanoparticles that lead to an inability to successfully regulate manufacturers. Research has also been conducted on the hazardous effects of nanoparticles on the human body and environment. We decided to compose a policy brief highlighting the existing challenges in nanoparticle regulation and the lessons learned from previous failure to regulate new chemical substances. The brief was sent out to regulatory agencies, government agencies, and news outlets to raise awareness about the issue. We feel responsible to let others know about the damage nanoparticle waste can do to the environment. (Policy Brief created by Ashley L.)

We sent this policy brief to the Environmental Protection Administration (EPA) minister in Taiwan, and they responded! They read our policy brief and said that they will take it into consideration when they make policy regulations on the use of nanoparticles in the future. They understand that nanotechnology is still developing and definitely needs more attention and regulation. (Correspondence: Christine C.)