| Line 168: | Line 168: | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

<h4 class="para col-lg-12">We separated our Human Practices into three categories: <b>Research, Impact, and Outreach</b>. Each category serves to guide and help us better understand our project. In addition to contacting professors, engineers, researchers, companies, and wastewater treatment plants (WWTP) to compile information for our final constructs and prototype designs, we also reached out to the public to raise awareness of synthetic biology and nanotechnology. | <h4 class="para col-lg-12">We separated our Human Practices into three categories: <b>Research, Impact, and Outreach</b>. Each category serves to guide and help us better understand our project. In addition to contacting professors, engineers, researchers, companies, and wastewater treatment plants (WWTP) to compile information for our final constructs and prototype designs, we also reached out to the public to raise awareness of synthetic biology and nanotechnology. | ||

| + | |||

</h4> | </h4> | ||

| Line 178: | Line 179: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

| − | <h4 class="para col-lg-12">To understand how people view nanoparticles (NPs), | + | <h4 class="para col-lg-12">To understand how people view nanoparticles (NPs), as well as NP usage and current regulations, we gathered public opinion from our local community. We sought advice from researchers in the fields of nanotechnology and environmental science to learn about the impact of NPs on the environment and our lives. Lastly, we contacted NP manufacturers, waste collectors, as well as wastewater treatment plants (WWTP) in both urban and rural settings to learn about current practices and possible future applications. |

| + | |||

</h4> | </h4> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 211: | Line 213: | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

<h4 class="para col-lg-12"> | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> | ||

| − | Not all WWTPs are as large as the one in Taipei. One of our advisors (Jude Clapper) went to visit the Boswell WWTP in rural southwestern Pennsylvania. We learned that the same processes that occur in the Taipei Dihua WWTP also occur in the Boswell WWTP, but with different water flow rates and waste quantities. | + | Not all WWTPs are as large as the one in Taipei. One of our advisors (Jude Clapper) went to visit the Boswell WWTP in rural southwestern Pennsylvania. We learned that the same processes that occur in the Taipei Dihua WWTP also occur in the Boswell WWTP, but with different water flow rates and waste quantities. Since both facilities use a similar water purification process, we were inspired to create our current prototype design--a rotating polymeric bioreactor coated in biofilm--which is applicable to both WWTPs. This prototype will be placed in the secondary sedimentation tank, where the majority of organic solids have been removed and only smaller particles exist. The plant manager, Robert J. Blough, also confirmed that since our project is bacteria-based, it will be killed by UV light and chlorine in the disinfection tank, similar to the Dihua WWTP, before the water turns into effluent and goes to the rivers and oceans. |

</h4> | </h4> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 217: | Line 219: | ||

<div class="image_container col-lg-10 col-lg-offset-1"> | <div class="image_container col-lg-10 col-lg-offset-1"> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/2/2f/T--TAS_Taipei--BoswellDiagram-new.jpg" alt="test" id="group"> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/2/2f/T--TAS_Taipei--BoswellDiagram-new.jpg" alt="test" id="group"> | ||

| − | <h4 class="subtitle">We plan to add our bacteria either | + | <h4 class="subtitle">We plan to add our bacteria to either the deep aeration tanks or the secondary sedimentation tanks. The disinfection tank will then kill the bacteria used in previous tanks.<span class="subCred">Figure: Christine C.</span></h4> |

</div> | </div> | ||

</div><br> | </div><br> | ||

| Line 226: | Line 228: | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row" id="tap"> | <div class="row" id="tap"> | ||

| − | <h1 class="section-title col-lg-12"> | + | <h1 class="section-title col-lg-12">Taipei Museum of Drinking Water</h1> |

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

<h4 class="para col-lg-12"> | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> | ||

| − | We visited the | + | We visited the Taipei Museum of Drinking Water hoping to find out more about how tap water is treated. We learned that water filtration methods vary in different areas of Taiwan, with Taipei’s filtration method being the simplest since the water is relatively clean compared to other regions, such as Kaohsiung, where the city is heavily industrialized. In Taipei, the source of tap water comes from a protected zone upstream of Xindian river. We also learned that they use sedimentation tanks and flocculation to help clump up and remove impurities. Due to the lack of a disinfection step, however, we realized that our project would not be applicable here, since our project depends on the use of <i>E. coli</i> bacteria. (Whole team activity) |

</h4> | </h4> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 249: | Line 251: | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

<h4 class="para col-lg-9"> | <h4 class="para col-lg-9"> | ||

| − | Before we started to conduct experiments, we emailed Dr. Eric P. Lee, senior member of technical staff at Maxim Integrated, and TAS alumnus, to ask him some general questions about | + | Before we started to conduct experiments, we emailed Dr. Eric P. Lee, senior member of technical staff at Maxim Integrated, and TAS alumnus, to ask him some general questions about the approach of our project. We asked him about our two approaches, one with <i>E. coli</i> receptors that bind to the capping agents of NPs, the other with biofilm that traps NPs. Dr. Lee suggested that our membrane receptor must be specific to a particular capping agent. He also commented that the biofilm approach was a good idea since we could trap multiple types of NPs regardless of their capping agent. (Interviewed by Emily C.) |

</h4> | </h4> | ||

<div class="image_container col-lg-3"> | <div class="image_container col-lg-3"> | ||

| Line 260: | Line 262: | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

<h4 class="para col-lg-12"> | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> | ||

| − | We interviewed Professor Roam of National Central University and former general director of the Environmental Analysis Labs (EAL) of the Taiwan Environmental Protection | + | We interviewed Professor Roam of National Central University and former general director of the Environmental Analysis Labs (EAL) of the Taiwan Environmental Protection Administration (EPA) to learn more about the background and potential threat of NPs. Dr. Roam informed us that the most common NPs used in Taiwan include: TiO<sub>2</sub>, ZnO, Ag, Au, Fe, Carbon Nanotubes, Fullerenes, Clay, and Graphene. He also told us that the toxicity of a NP is directly related to its size, but there are currently no regulations or guidelines that specify the toxicity of different types and sizes of NPs. With the increased use of NPs in society, Dr. Roam believes that more attention should be placed on waste management, risk assessment and regulations. |

</h4> | </h4> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

<div class="row"> | <div class="row"> | ||

<h4 class="para col-lg-12"> | <h4 class="para col-lg-12"> | ||

| − | After our first visit to the Dihua WWTP, we learned that the sludge removed from wastewater is either 1) sent to landfills, 2) used as fertilizer, or 3) incinerated. We asked Dr. Roam if | + | After our first visit to the Dihua WWTP, we learned that the sludge removed from wastewater is either 1) sent to landfills, 2) used as fertilizer, or 3) incinerated. We asked Dr. Roam if aggregated NPs in the waste sludge would still be harmful to the environment if disposed using current methods. He said that all of these sludge disposal solutions are still harmful to the environment, but they are better than letting NPs flow into bodies of water. He advised us to target removal of NPs in the wastewater treatment process before it is discharged. (Interviewed by Candice L. and Justin Y.) |

</h4> | </h4> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| Line 276: | Line 278: | ||

<div class="image_container col-lg-5"> | <div class="image_container col-lg-5"> | ||

<img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/4/46/T--TAS_Taipei--Roam_Info-min.jpg" alt="test" id="group"> | <img src="https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/4/46/T--TAS_Taipei--Roam_Info-min.jpg" alt="test" id="group"> | ||

| − | <h4 class="subtitle">Materials | + | <h4 class="subtitle">Materials provided to us by Professor Roam.<span class="subCred"></span></h4> |

</div> | </div> | ||

Revision as of 12:31, 31 October 2017

X

Project

Experiments

Modeling

Prototype

Human Practices

Safety

About Us

Attributions

Project

Experiment

Modeling

Prototype

Human Practice

Safety

About Us

Attributions

hi

HUMAN PRACTICES SUMMARY

We separated our Human Practices into three categories: Research, Impact, and Outreach. Each category serves to guide and help us better understand our project. In addition to contacting professors, engineers, researchers, companies, and wastewater treatment plants (WWTP) to compile information for our final constructs and prototype designs, we also reached out to the public to raise awareness of synthetic biology and nanotechnology.

RESEARCH

To understand how people view nanoparticles (NPs), as well as NP usage and current regulations, we gathered public opinion from our local community. We sought advice from researchers in the fields of nanotechnology and environmental science to learn about the impact of NPs on the environment and our lives. Lastly, we contacted NP manufacturers, waste collectors, as well as wastewater treatment plants (WWTP) in both urban and rural settings to learn about current practices and possible future applications.

Water System Services

Dihua Wastewater Treatment Plant

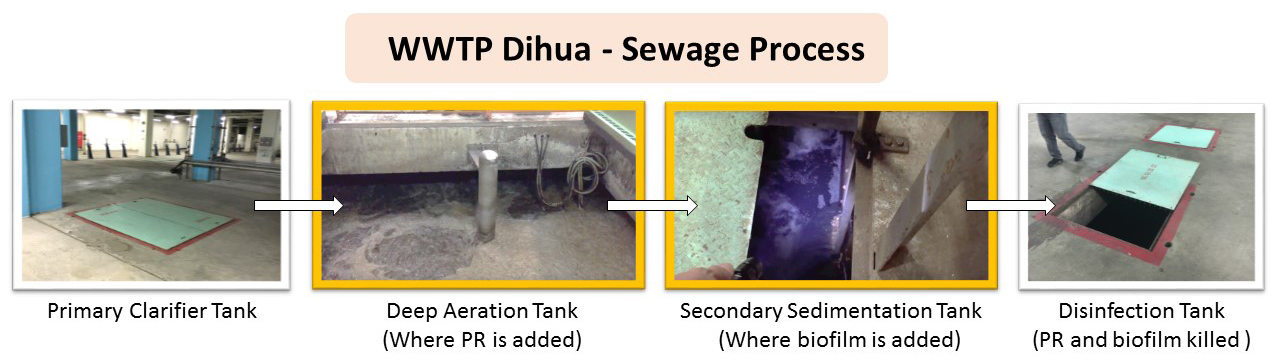

In order to learn firsthand about the effect of NPs in WWTPs, we visited the Dihua WWTP (迪化污水處理廠). Here, we were given a tour around the plant, and were able to ask questions to the managers and people who work there. They confirmed that the current facilities are unable to remove NPs from wastewater mainly due to their small size. In addition to this information, they kindly provided us with samples of sludge, effluent water, and the polymers they add during the wastewater treatment process. Throughout the year, we visited and talked to the Dihua WWTP several times about where and how our project could be implemented in their current system. These conversations and visits played a huge role in shaping our construct design, prototype design, mathematical modeling and overall purpose for our project. (Whole team activity)

We plan to add our bacteria to either the deep aeration tanks or the secondary sedimentation tanks. The disinfection tank will then kill the bacteria used in previous tanks.Figure: Christine C.

Boswell Wastewater Treatment Plant

Not all WWTPs are as large as the one in Taipei. One of our advisors (Jude Clapper) went to visit the Boswell WWTP in rural southwestern Pennsylvania. We learned that the same processes that occur in the Taipei Dihua WWTP also occur in the Boswell WWTP, but with different water flow rates and waste quantities. Since both facilities use a similar water purification process, we were inspired to create our current prototype design--a rotating polymeric bioreactor coated in biofilm--which is applicable to both WWTPs. This prototype will be placed in the secondary sedimentation tank, where the majority of organic solids have been removed and only smaller particles exist. The plant manager, Robert J. Blough, also confirmed that since our project is bacteria-based, it will be killed by UV light and chlorine in the disinfection tank, similar to the Dihua WWTP, before the water turns into effluent and goes to the rivers and oceans.

We plan to add our bacteria to either the deep aeration tanks or the secondary sedimentation tanks. The disinfection tank will then kill the bacteria used in previous tanks.Figure: Christine C.

Taipei Museum of Drinking Water

We visited the Taipei Museum of Drinking Water hoping to find out more about how tap water is treated. We learned that water filtration methods vary in different areas of Taiwan, with Taipei’s filtration method being the simplest since the water is relatively clean compared to other regions, such as Kaohsiung, where the city is heavily industrialized. In Taipei, the source of tap water comes from a protected zone upstream of Xindian river. We also learned that they use sedimentation tanks and flocculation to help clump up and remove impurities. Due to the lack of a disinfection step, however, we realized that our project would not be applicable here, since our project depends on the use of E. coli bacteria. (Whole team activity)

Nanoparticle & Wastewater Experts

Dr. Eric Lee

Before we started to conduct experiments, we emailed Dr. Eric P. Lee, senior member of technical staff at Maxim Integrated, and TAS alumnus, to ask him some general questions about the approach of our project. We asked him about our two approaches, one with E. coli receptors that bind to the capping agents of NPs, the other with biofilm that traps NPs. Dr. Lee suggested that our membrane receptor must be specific to a particular capping agent. He also commented that the biofilm approach was a good idea since we could trap multiple types of NPs regardless of their capping agent. (Interviewed by Emily C.)

Dr. Gwo-Dong Roam

We interviewed Professor Roam of National Central University and former general director of the Environmental Analysis Labs (EAL) of the Taiwan Environmental Protection Administration (EPA) to learn more about the background and potential threat of NPs. Dr. Roam informed us that the most common NPs used in Taiwan include: TiO2, ZnO, Ag, Au, Fe, Carbon Nanotubes, Fullerenes, Clay, and Graphene. He also told us that the toxicity of a NP is directly related to its size, but there are currently no regulations or guidelines that specify the toxicity of different types and sizes of NPs. With the increased use of NPs in society, Dr. Roam believes that more attention should be placed on waste management, risk assessment and regulations.

After our first visit to the Dihua WWTP, we learned that the sludge removed from wastewater is either 1) sent to landfills, 2) used as fertilizer, or 3) incinerated. We asked Dr. Roam if aggregated NPs in the waste sludge would still be harmful to the environment if disposed using current methods. He said that all of these sludge disposal solutions are still harmful to the environment, but they are better than letting NPs flow into bodies of water. He advised us to target removal of NPs in the wastewater treatment process before it is discharged. (Interviewed by Candice L. and Justin Y.)

Professor Gwo-Dong Roam (left) of National Central University and former general director of the Environmental Analysis Labs (EAL) of Taiwan EPA.

Materials provided to us by Professor Roam.

Thomas J. Brown

Thomas J. Brown, the Water Program Specialist of the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) occasionally helps with the Boswell Wastewater Treatment Plant. He has also worked with the EPA in Taiwan on wastewater treatments. We interviewed Mr. Brown about our methods to clean NPs in WWTPs and how to achieve our goal of implementation. With his expertise in the field of wastewater treatment, he provided us some suggestions as to how we could turn our project into reality.

For example, we asked him if there were differences between rural and urban plants that we should take into consideration when thinking about implementing our project. He responded that the biological processes used for treatment remains the same regardless of facility size. This helped us think about and design our final prototype, which can potentially be used in both rural and urban treatment plants.

Nanoparticle Manufacturers & Disposal Services

Apex Nanotek

To learn more about the applications of NPs, we visited a nanotech company that uses silver NPs to make various antimicrobial products. The researcher and manager of Apex Nanotek, Chery Yang, introduced us to their main product, which is antimicrobial nanosilver activated carbon. Pure activated carbon, commonly used to treat sewage and industrial exhaust, is prone to bacterial growth. To overcome this problem, they integrate crystallized nanosilver into the activated carbon for their antimicrobial effects. One of their products is a showerhead, with nanosilver activated carbon filters to kill bacteria when water flows through the showerhead.

We tested the product by comparing SEM images between tap water and filtered water from the showerhead. The showerhead decreased the number of bacteria and larger particles from tap water! However, we also observed the release of NPs from the filter, which will flow into wastewater. (Interviewed by Christine C., Kelly C., Yvonne W., Chansie Y., and Justin Y.)

Chery Yang (third person from the left), the main researcher of Apex Nanotek Corporation

Product of Apex Nanotek: Silver Spring Shower Head.

The image on the left shows a tap water sample under the SEM, in which we observed some bacteria (round objects that are approximately 1 μm in diameter). The SEM image on the left shows water that was filtered by the showerhead from Apex nanotek. There is less bacteria as the showerhead uses embedded nanosilver antibacterial filters.(SEM images: Christine C. and Florence L.)

THEPS Environmental Protection Engineering Company (中港環保工程股份有限公司)

We contacted the company that removes our NP waste because we wanted to know what happens when it leaves our lab. They directed us to National Cheng Kung university who actually treats the waste for them. The university uses chemicals and burning to aggregate NPs. Through literature research, we discovered that burning NPs is the most prevalent way for removal, however it is not 100% effective at removing all types of nanomaterials (Marr et. al. 2013). (Interviewed by Katherine H, Audrey T. and Christine C.)

Public Opinion

Survey Results

We created a survey that helped us identify public knowledge and misconceptions about synthetic biology and NP usage. Over 240 people completed the survey. (Survey created by Abby H., Christine C. and Emily C.)

Here are some results from our survey:

General Questions

- The majority of people think that gene modification is acceptable if the goal is to save or improve quality of life; however, it is not acceptable for non-medical related reasons, such as changing hair or eye color. In addition, most people do not have a preference between chemical or biological drug synthesis. These results suggest that people are accepting of genetic engineering when it is related to health and medicine.

- Environmentally, people are generally concerned with the wastewater that enters the ocean and the river. This gives weight to our project, because the quality of water is an important concern for the general public.

Two examples of general questions from our survey. (Left) 87% (201 out of 243 total responses) think that genes should be modified if the goal is to save or improve quality of life. (Right) 96.7% of the people surveyed care about the quality of wastewater (236 out of 244 total responses).Figure: Christine C.

Project-Specific Questions

- The majority of people have heard of NPs and know that NPs are used in consumer products; however, they do not know why NPs are used.

- Most people believe that the government and NP manufacturers should share responsibility for the regulation of NP usage and disposal.

Two examples of project-specific questions from our survey. (Left) A majority of the people we asked (58.6%) do not know why NPs are used in consumer products (143 out of 244 total responses). (Right) People believe that NP manufacturers and the government (including WWTPs) are most responsible for the regulation of NP usage and disposal. Figure: Christine C.

Bioethics Panel

We hosted a Bioethics Panel, where we invited students and teachers to discuss the moral, social and environmental concerns of our project. To encourage participants to consider the problems from multiple perspectives, we created a role-playing game and assigned different roles to participants. We then asked for their opinions on NP usage and disposal from the perspective of their assigned role. (Whole team activity)

For instance, one of our questions was:

“Dihua WWTP has no nanoparticle removal plan. Should this be the job of the wastewater plant? Or the nanoparticle manufacturer?”

The following roles were assigned:

- Wastewater plant manager

- Nanoparticle manufacturer

- Citizen

- Fisherman

- Fish

Most of the wastewater plant managers thought that NP manufacturers should be responsible for removing NPs, because they have more information (e.g., solubility, toxicity, etc.) about their own products. However, many other participants were skeptical that manufacturers could be trusted to remove their own contamination and agreed that WWTPs should ultimately be responsible for cleaning water contaminated with NPs.

This activity gave us great insight on how the public perceives NP usage and regulation in society. This also gave us a chance to talk to people about both the benefits and the dangers of using NPs.

IMPACT

Even though we can’t implement our project in an actual wastewater treatment system, we still wanted to make a difference! We decided on two areas where we could make an immediate impact: 1) Creating an policy brief to highlight current obstacles in effective NP regulation and propose new policy solutions, and 2) Raising funds for two organizations that promote environmental protection.

Policy Brief -- Nanoparticle Regulation Issues & Case Studies

Our team has conducted extensive research on existing regulatory laws and policies regarding NPs and nanomaterials. We have investigated chemical regulations, including the Restriction, Evaluation, Authorization, and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH), A Toxic Substances Control Act (TCSA), CLP, and the Clean Air Act (CAA). There are significant obstacles to successfully regulating NPs, such as conflicting definitions on NPs that lead to an inability to successfully regulate manufacturers. Research has also been conducted on the hazardous effects of NPs on the human body and environment. We decided to compose a policy brief highlighting the existing challenges in NP regulation and the lessons learned from previous failure to regulate new chemical substances. The brief was sent out to regulatory agencies, government agencies, and news outlets to raise awareness about the issue. We feel responsible to let others know about the damage NP waste can do to the environment. (Policy Brief created by Ashley L.)

We sent this policy brief to the Environmental Protection Administration (EPA) minister in Taiwan, and they responded! They read our policy brief and said that they will take it into consideration when they make policy regulations on the use of NPs in the future. They understand that nanotechnology is still developing and definitely needs more attention and regulation. (Correspondence: Christine C.)

Click to see his reply!

Minister Lee Ying Yuan of the EPA

Our nanoparticle regulation policy brief was published by two media outlets, News Lens International and The China Post. Combined, the two newspapers have over 600,000 daily readers. We emphasized that the lack of regulatory legislation prevents agencies from acquiring regulatory power. We also talked about the lack of nanoparticle filtration in wastewater treatment plants. (Interview by Ashley L.)

Fundraising & Donation

We held multiple fundraising sales, selling small ice cream dots (resembling NPs!) and Oreo fudge during our lunch periods in school, and making “glitter slime” at our school’s annual spring fair (see Spring Fair in the Outreach section above). (Team activity)

In total, we raised over 500 USD, and donated the money to two organizations:

WaterisLife is an organization that provides clean drinking water, as well as sanitation and hygiene education programs to schools and communities in need. We donated to this organization in hopes that more people will have access to clean water. Visit WaterisLife here.

Taiwan Environmental Protection Union (TEPU) is a local organization founded in 1987 to promote public awareness and participation to prevent pollution and damage to public resources. Visit TEPU here.

OUTREACH

In Outreach, we raised awareness of the beneficial qualities and harmful consequences associated with NPs. We also educated the general public about NP usage, synthetic biology, and science in general. Lastly, we communicated with other iGEM teams to share ideas and collaborate on experiments.

Education

Kindergarten -- Observing the “invisible”

Our iGEM team hosted over 120 kindergarten students to teach them the power of observation and the basics of science. For example, we taught them how to use microscopes to look at anti-counterfeiting measures on paper money and how to use refraction lenses to see that white light is made up of various colors. (Whole Team activity)

7th Grade Introduction to Synthetic Biology

We introduced iGEM and the basics of synthetic biology to all 200+ students in the seventh grade. They learned how to use micropipettes, as well as how to load and run dyes through an agarose gel. We also gave students different real world problems. Using paper biobrick parts, students put together constructs that would solve the given problems. (Whole Team activity)

Spring Fair -- Spreading Public Awareness of Nanoparticles

At our school’s annual spring fair, we manned a booth where people could create their own glitter slime by mixing polyvinyl alcohol and sodium borate solutions. The slime was meant to simulate the biofilm we use to trap NPs (in this demo, glitter) in WWTPs. We also showed a few SEM images of bacteria, as well as everyday products that contain NPs such as toothpaste and sunscreen. Everyone who came by our booth was encouraged to take our survey so we could record opinions on bioethics and concerns about NPs. (Whole team activity)

iGEM Slime booth at Spring Fair along with the iPad surveys set up next to the tables.

SEM images that show nanoparticles in daily products (ex: toothpaste and sunscreen)

Research Symposium -- Poster & Oral Presentations

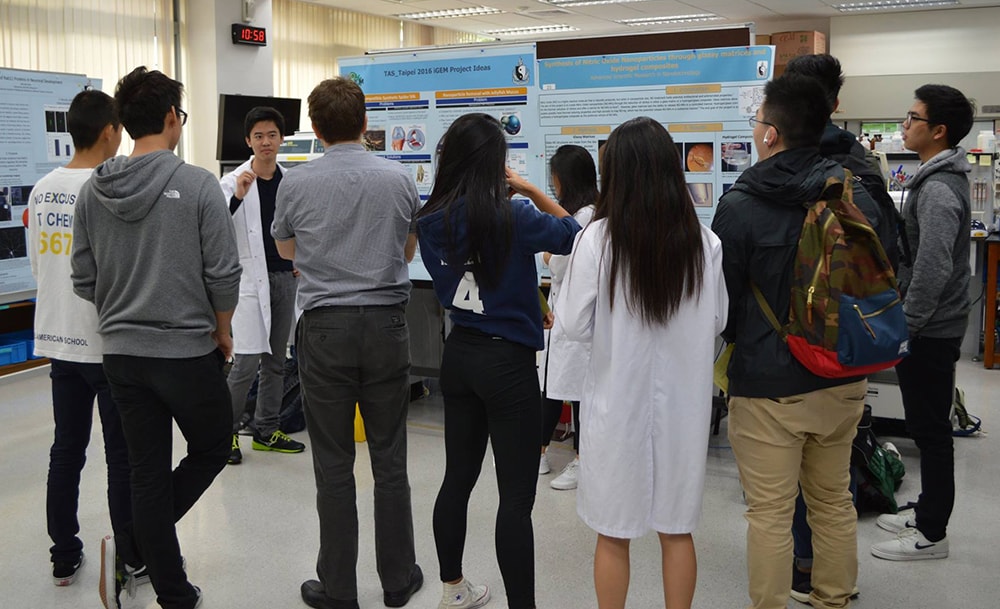

At TAS we conduct research symposiums twice a year to showcase the research of students who take a variety of research courses. Before we decided our project topic, we developed 4 different project ideas to present at our first research symposium (poster session). We received feedback from both students and teachers, then decided on our current project. At our second research symposium, we presented on our current project, Nanotrap! (Presenters: Candice L., William C., Chansie Y., Christine C., Yvonne, W., Justin Y., Dylan L., and Catherine Y.)

5th Annual Asia-Pacific iGEM Conference -- NCTU

In preparation for the Giant Jamboree, we attended the 5th annual Asia-Pacific iGEM conference at NCTU to share and receive valuable feedback from other college and high school teams in Taiwan. This event allowed us to consider different aspects of our project using feedback from other teams. (Presenters: William C., Yvonne W., and Justin Y.)

Public Outreach -- A Tour of Taipei

Some members of the iGEM team went to various popular sites in Taipei to pass out flyers and conduct surveys. We visited National Taiwan University, Chiang Kai-Shek Memorial Hall, and Taipei 101. This helped us collect feedback from different age groups and backgrounds. This was a great and fun way to spread awareness of NP pollution! (Team members: Ashley L., Emily C., Florence L., Candice L., Yvonne W., Justin Y., Avery W., Christine C., Jesse K., and Laurent H.)

Collaborations

NYMU_TAIPEI

We have continued and strengthened our long standing partnership with National Yang Ming University (NYMU_Taipei). NYMU_TAIPEI troubleshooted our cloning procedure and design of primers, gave us protocols for assaying biofilm production, and trained our future iGEMers (Leona and Catherine).

In return, we helped add to the characterization of their lactose-induced suicide mechanism: the Holin-Endolysin-NrtA system (BBa_K2350021). We measured the population of their kill-switch bacteria in different lactose concentrations, and find that our results are consistent with their findings.

We independently tested the function of NYMU_Taipei’s lactose-induced kill-switch system. Different concentrations (0-250 mM) of lactose were tested for their effects on bacteria population. Experiment: Yvonne Wei

Additionally, this year two members from TAS (Catherine and Leona) are members on both NYMU and TAS teams. They learned the cloning cycle from TAS and helped run experiments and human practices for NYMU throughout the year. In Boston, they will also help NYMU present their project at the Giant Jamboree.

CGU_Taiwan

We first met the CGU_Taiwan team at the end of our presentation for the Asia Pacific iGEM Conference hosted in National Chiao Tung University (NCTU).

They were excited that our biofilms were able to trap nanoparticles and inquired whether they trapped ink particles similarly well. CGU_Taiwan is working on improving the procedure to manufacture reprocessed paper. They found that a process called “flotation,” typically used to de-ink paper, could cause significant paper fiber loss. They wondered if biofilm could potentially replace the current flotation process to preserve paper fibers. We offered to test this for CGU_Taiwan. We used a similar experimental procedure as our preliminary biofilm trapping experiment. The results suggest that biofilms can trap ink particles. As shown below, the relative absorbance of ink decreased by approximately 50% when mixed with biofilm.

From left to right: control (biofilm only), control (ink only), biofilm mixed with 0.1x ink solution. More ink was pulled down when mixed with biofilm, and the color of the supernatant is clearer than the supernatant of the ink only group. Experiment: William Chen, Yvonne Wei

In return, CGU_Taiwan helped us independently verify that overexpression of OmpR234 (BBa_K2229200) produces more biofilms than control (BBa_K342003).