Modelling PLP production

The problem

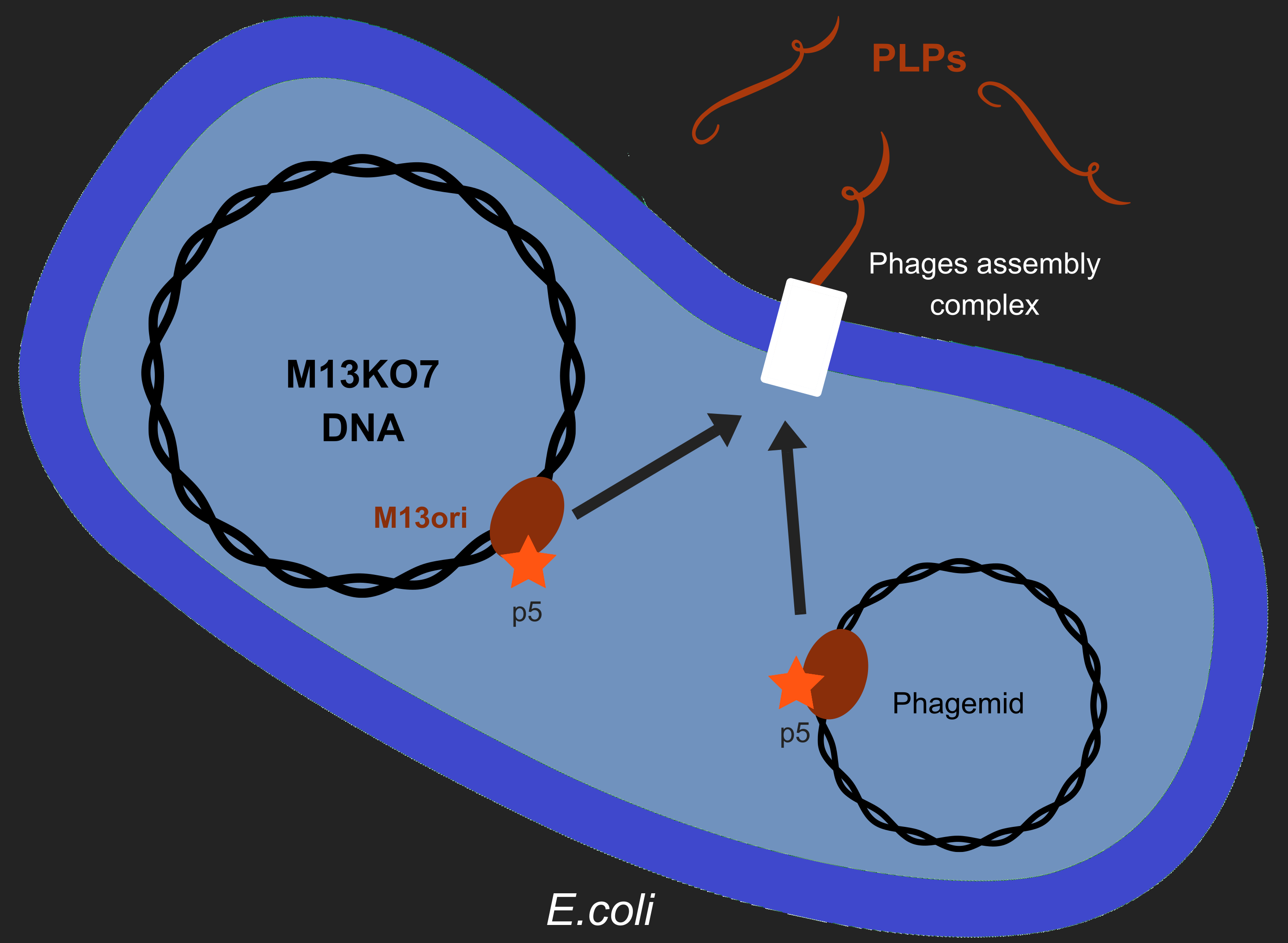

Our objective is to produce phage like particles (PLPs), for this, the bacteria must contain both a helper phage and a phagemid (Figure 1). During phage production, several key events determine which DNA molecules are packaged into phages or PLPs. These involve recognition of the M13 replication origin by several phage proteins.

A major hurdle to marketing KILL XYL is obtaining the necessary authorizations. Our interviews and legislation study both showed that the number of viable phages could be a problem. We therefore decided to measure and model the ratio between viable phage and phage-like particles, and so try to optimize this ratio to facilitate the preparation of pure PLPs.

The Model

We based our model on a recently published model of "wild-type" M13 replication [1][2].

This model was modified to accommodate the fact our system has two plasmids (Helper and Phagemid) while the previously modeled system has only one. This means we incorporated: the presence of a phagemid, with its own replicative origin and M13 origin, the helper-phage E. coli plasmid origin and the modification of the helper-phage M13 origin. This was done by adapting the existing model and adding new parts to the existing model. These modifications added 9 species and 3 parameters and 13 equations to the original model, and changed 8 parts of the previous model.

We observed we could roughly reproduce the published copy number of plasmids by tweaking our parameter describing the affinity of DNA polymerase for the plasmid's origin of replication ("Polymerase Binding Event") in our model when the reactions describing phage formation were inactivated. This is a purely empirical observation. To the best of our knowledge, there is no published data describing this parameter, which is why we assumed published data for plasmid copy number can be used as a proxy to approximate the proclivity of DNA polymerase to bind the plasmid's origin of replication.

The modified model is available File:T--Aix-Marseille--Model.zip

We used the initial measurement to constrain parameters of the model.

Results

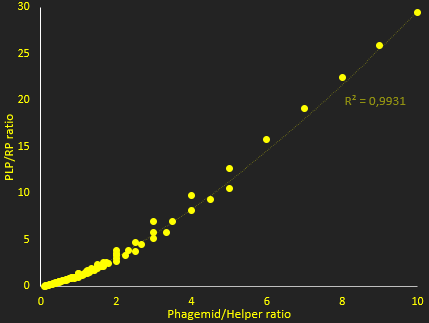

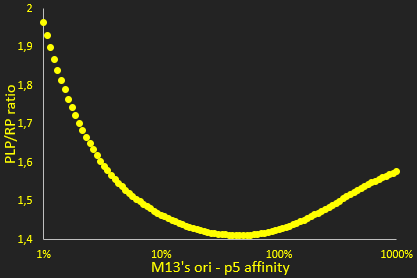

The packaging ratio depends on two main parameters: the ratio of transformed phagemid and helper phage (Figure 2), and the difference in p5 affinity for eitheir plasmid's M13 ori (Figure 3).

In figure 2, we investigate how the ratio of PLPs to replicative phage depends on the copy number of the two plasmids used. This shows that higher copy numbers of phagemid increases this ratio. This simulation showed essentially that reasing copy number amplify packaging efficiency, and ratio of PLPs to phage. The result hides however, that at very high ratios, the lack of protein reduces production. Nevertheless, and in view of this result for the tests we used a backbone that gives, in theory, a very high copy number for the phagemid, to try and maximize the ratio of PLPs to phages.

The next parameter we investigated was the relative affinity between p5 and M13 origin of replication (Figure 3). This affinity is critical to determine whether single-stranded DNA is used for packaging or making additional double-stranded DNA. This graph shows a clear minimum where the PLPs to phage ratio is the least favorable. However, as we are interested in the left-hand part of the graph, the efficiency of the M13 origin can be reduced but not easily improved, we see that lower efficiencies improve the ratio. Nevertheless, our results show a much lower sensitivity to this parameter than we initially expected.

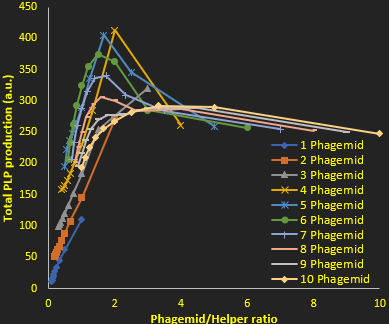

As we found above (Figure 2), the higher the phagemid to helper phage ratio the better is the PLP production. However, this enhanced purity is offset by a drop in the amount of PLPs produced, due to a lack of proteins (which are encoded by the helper phage). This is why we also investigated the total PLP production as a function of phagemid to helper ratio (Figure 4). We determined that about 10 phagemids and 2 helper phages per cell is optimum in long term for PLP production. This result allows us to redesign the origins of replication and selection pressures to optimize PLP production.

p15A is the origin of replication of M13KO7 in E.coli and has a copy number of about 10 [3]. Since the best phagemid/helper ratio is 5:1, we need a phagemid with a replication origin that gives a copy number near 50. This is not obvious from the table however possibly by using different antibiotic concentrations and a phagemid with a pColE1 replication origin we could optimize this ratio.

Conclusions

Our measurements show the initial design needs to be improved to increase the proportion of PLP produced. This is important to optimize production of PLP and facilitate purification.The model showed us that the most important parameters in determining the proportion of PLP produced are plasmid copy number and affinity between the M13 origin and protein p5, as shown in figures 2 and 3. However, plasmid copy number also plays a role in total PLP yield as shown in figure 4.

Our initial reaction, from early results, was to use a very high copy number plasmid, pBluescript, to ensure a maximal PLP to phage ratio. Experimentally this was not very effective as we can see from our measurements.

The model we have made of PLP production suggests it's necessary to redesign certain features. We should especially take into account the role played by plasmid copy number and choose our backbones to ensure the right equilibrium between protein production and DNA production. The model suggests a helper:phagemid ratio of 1:5. Therefore, we should complement the p15A origin of M13KO7 with a phagemid with fewer copies than pBluescript[3] like a pColE1 replication origin.

In a nutshell, our modeling modified our wet-lab approach by directing us towards pBluescript as a very high copy number plasmid. However, a detailed analysis suggests that a enhance PLP production might be obtained with a different balance between protein and DNA production.

The mathematical model we have produced can clearly be improved, and aspects that we have not included, that deserve incorporation, are the:

- influence of antibiotics on copy number for plasmids and phages containing a resistance cassette;

- influence of replication origin on maintained copy number;

- effects of M13 origin on duplication of phage RF.

Nevertheless, our experiments have helped us parametrize our model, which had guided the wet-lab experiments and indicate how to improve PLP production.

References

- ↑ Smeal et al, Simulation of the M13 life cycle I: Assembly of a genetically-structured deterministic chemical kinetic simulation, Virology, 500, January 2017

- ↑ Smeal et al, Simulation of the M13 life cycle II: Investigation of the control mechanisms of M13 infection and establishment of the carrier state, Virology, 500, January 2017

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 http://blog.addgene.org/plasmid-101-origin-of-replication