HUMAN PRACTICES GOLD

Our team has made human practices the foundation of our project to ensure that we fully understand and address current global issues. After contacting health practitioners around the world about their experience working in remote regions that struggle with accessibility to essential medicines and supplements, we were able to identify specific issues in need of attention and discuss how we can use synthetic biology to address them. Through outreach efforts in our local community, we better understood the social and cultural controversies and perspectives on GMO’s, medicine delivery, and how to address such historically sensitive subjects. Additionally, critically analyzing how our project disrupts existing processes made us think about why current methods of delivery are relatively unsuccessful and how our project could address the drawbacks while maintaining the beneficial factors of existing methods. The knowledge we gained from these efforts became the driving force behind the design of our project.

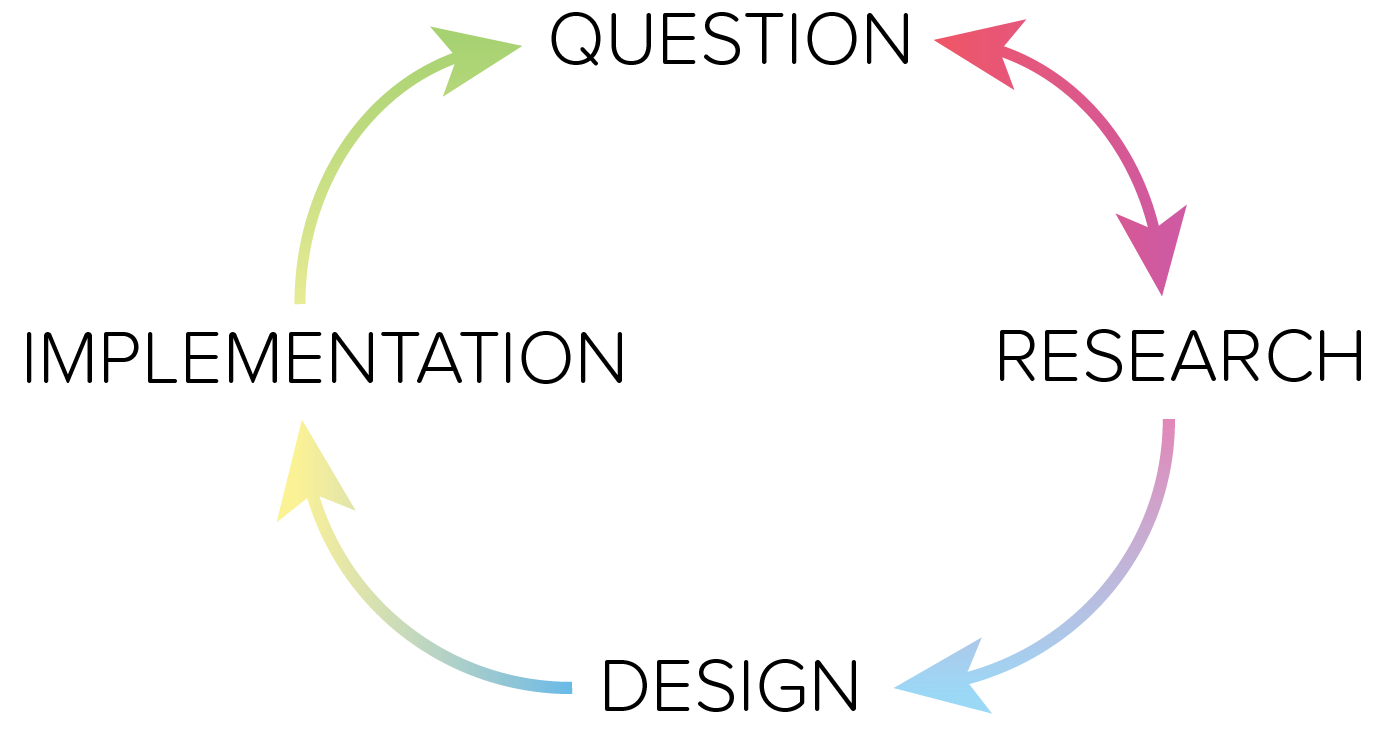

Developing a potential solution to a real-world problem is a largely dynamic process.

Developing a potential solution to a real-world problem is a largely dynamic process.

To do any real work, we must first ask important questions. While we mentioned some important questions in the human practices silver page, those merely guided us in choosing how to narrow our focus. With preliminary questions comes research, and with research comes design, and with design comes implementation. Although, with implementation comes more questions related to social and cultural implications, and of course, whether or not the project of interest is actually good for the world.

On this page, we’ll discuss the more important questions we asked and the outreach, engagement, and research we did to answer them.

News headlines from various reports of either stolen, blocked, or seized medical aid.

News headlines from various reports of either stolen, blocked, or seized medical aid.

Why Bugs Without Borders?

Or more specifically, why localized medicine production?

First and foremost: medicine is hard to ship. Current efforts to ship medicine are unsustainable and unreliable, and rarely do the shipments make it to the intended destination. So why keep trying to ship the medicine synthesized in centralized large pharmaceutical companies? Instead, let’s ship the factory, once, and make the medicines locally in the regions that need them the most.

We hope to accelerate a growing movement to shift production of medicine delivery to the regions that need them. While it is important for us to develop the technology, essentially a living factory synthesizing essential vitamins and medicines, it is also important for us to address aspects of the problem unsolvable with science alone. We hope to analyze and understand how our project fits into existing policies and attitudes surrounding poverty and malnutrition.

Map of the international correspondence conducted before choosing our project. This outreach became the motivation behind our research focus.

Map of the international correspondence conducted before choosing our project. This outreach became the motivation behind our research focus.

Why is this an important issue?

We began our research by contacting health care practitioners around the world, including professionals in Brazil, Palau, Bolivia, Venezuela, Perú, Haití, Nicaragua, and The Dominican Republic. We asked these doctors what ailments are most common and what medicines are most needed. Nearly all the practitioners mentioned lack of adequate access to vitamins, pain relievers, and other pharmaceuticals due to insufficient supply, high cost, and high demand. By analyzing World Health Organization data, we noticed that malnutrition and pain are consistent global problems, especially in remote regions where medicine is generally less accessible. Therefore, we chose to focus on the topics of vitamin deficiency and pharmaceutical shortages.

For example, Dr. Lubin (GMT - Dominican Republic/Haiti) stated that antipyretics and anti-inflammatories are commonly needed, and that medicines for chronic treatments are highest in demand. Dr. Jacquelin Zubiaga (GMT - Peru) elaborated upon experience in Peru, saying anti-inflammatories, topical creams, and digestive medicine are most in demand. Dr. Zubiaga explained furthermore, that vitamins there are expensive and sought-after, so a large part of what Zubiaga does is to educate patients on what specific vitamins do and what they will help with specifically. This calls to attention that educating patients is just as important as meeting the need for medicines.

Why a GMO?

Bioengineering an organism introduces the risks associated with a genetically modified organism, but relieves the risk of simply not having the medicine at all, and reduces dependency on shipments. The biosynthetic process eliminates the risk of adding toxic ingredients, a situation that has happened in poorly regulated conventional production factories[2].

Additionally, health care is outrageously expensive and often culturally invasive when forced upon people. For example, the Marshallese people who were eradicated from their homeland due to the extensive nuclear testing conducted by the U.S. Government in the 1940s and 50s have faced insurmountable difficulty coping with and affording traditional health care[5].

Image sourced from NY Times, "For Pacific Islanders, Hopes and Troubles in Arkansas"

Image sourced from NY Times, "For Pacific Islanders, Hopes and Troubles in Arkansas"

Worshipers gathered on a Sunday at Faith Full Gospel Marshallese Church.

Part of the goal was to provide a new medicine delivery approach that could be integrated more easily into already accepted diets or customs. The cultural barriers to adequate medical treatment by western standards were expanded upon in our discussion about the Marshallese who are granted residency in the United States, who pay taxes, but are not allowed to vote or hold office, or citizenship. By using an edible, nutrient dense microorganism, we hope to ease the process of cultural acceptance and integration. This was an important area of discussion for us. To learn more, take a look at our education and outreach page here!