Figure (1): Results of the analysis of PtNTT2 using Phobius.

The 30 first amino acids are clearly recognized as a signal peptide. Ten transmembrane domains are predicted.

Figure (1): Results of the analysis of PtNTT2 using Phobius.

The 30 first amino acids are clearly recognized as a signal peptide. Ten transmembrane domains are predicted.

Figure (2): Schematic overview of the design of the different transporter variants.

The lacUV5 promotor was used together with a strong RBS (BBa_B0034) for all parts. All variants except for pSB1C3-PtNTT2 were also tagged with GFP (BBa_E0040). cMyc was used as a linker (based on BBa_K2082221).

Table (1): Designed and cloned plasmids for the analysis and characterization of PtNTT2.

| Plasmid Name | BioBrick Number | Characteristics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| pSB1C3-PtNTT2 | BBa_K2201004 | Only the cds | |

| pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(66-575) | BBa_ K2201001 | cds with lacUV5 promotor and a strong RBS (BBa_B0034) | |

| pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(31-575) | BBa_K2201005 | cds with lacUV5 promotor and a strong RBS (BBa_B0034), truncated version lacking the first 30 amino acids | |

| pSB1C3-PlacUV5-pelB-SP-PtNTT2 | BBa_K2201006 | cds with lacUV5 promotor and a strong RBS (BBa_B0034), native signal peptide replaced with the pelB signal peptide | |

| pSB1C3-PlacUV5-TAT-SP-PtNTT2 | BBa_K2201007 | cds with lacUV5 promotor and a strong RBS (BBa_B0034), native signal peptide replaced with a TAT signal peptide | |

| pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2-GFP | BBa_K2201002 | Fusion protein of BBa_ K2201000 with GFP (BBa_E0040), Myc epitope tag as linker (BBa_K2201181) | |

| pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(66-575)-GFP | BBa_K2201003 | Fusion protein of BBa_ K2201001 with GFP (BBa_E0040), Myc epitope tag as linker (BBa_K2201181) | |

| pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(31-575)-GFP | BBa_K2201011 | Fusion protein of BBa_K2201005 with GFP (BBa_E0040), Myc epitope tag as linker (BBa_K2201181) | |

| pSB1C3-PlacUV5-pelB-SP-PtNTT2-GFP | BBa_K2201012 | Fusion protein of BBa_K2201006 with GFP (BBa_E0040), Myc epitope tag as linker (BBa_K2201181) | |

| pSB1C3-PlacUV5-TAT-SP-PtNTT2-GFP | BBa_K2201013 | Fusion protein of BBa_K2201007 with GFP (BBa_E0040), Myc epitope tag as linker (BBa_K2201181) |

Figure (3): Shake flask cultivation of all PtNTT2 variants.

E. coli BL21(DE3) and E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PtNTT2, not expressing PtNTT2, were used as negative controls. Two biological replicates of each strain were cultivated and three technical replicates taken for each measurement. A clear difference in the growth rates can be observed, with E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2 and E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-TAT-SP-PtNTT2 showing the weakest growth. Both strains also show the longest lag phase, which is nearly twice as long as the lag phase of E. coli BL21(DE3). E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(66-575) and E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-pelB-SP-PtNTT2 show the best growth of all PtNTT2 variants, reaching the highest OD600.

Table (1): Final OD600 of all cultures.

The highest OD600 was reached by the wildtype E. coli BL21(DE3), the lowest by E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2.

| Strain | Final OD600 [-] | |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | 5.178 ± 0.046 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PtNTT2 | 4.638 ± 0.029 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2 | 2.499 ± 0.134 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(66-575) | 4.397 ± 0.062 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(31-575) | 3.802 ± 0.135 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-pelB-SP-PtNTT2 | 4.171 ± 0.051 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-TAT-SP-PtNTT2 | 2.735 ± 0.150 |

Figure (4): Graphical determination of µmax.

The highest specific growth rate was determined for each culture by plotting the natural logarithm of OD600 against the cultivation time. The slope of the linear regression through the exponential phase gives µmax.

Table (2): Maximum specific growth rates and minimum doubling times for all cultures.

| Strain | µmax [h-1] | td [h] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | 1.201 ± 0.070 | 0.577 ± 0.058 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PtNTT2 | 1.212 ± 0.029 | 0.572 ± 0.024 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2 | 0.978 ± 0.033 | 0.709 ± 0.034 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(66-575) | 1.194 ± 0.026 | 0.581 ± 0.022 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(31-575) | 1.143 ± 0.045 | 0.606 ± 0.039 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-pelB-SP-PtNTT2 | 1.189 ± 0.028 | 0.583 ± 0.024 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-TAT-SP-PtNTT2 | 0.946 ± 0.030 | 0.733 ± 0.032 |

Figure (5): Microcultivation of allPtNTT2 variants

E. coli BL21(DE3) and E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PtNTT2 (BBa_K2201004) were again used as negative controls. The same growth pattern as in the shake flask cultivation can be observed, with E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-pelB-SP-PtNTT2, E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(66-575) reaching the highest ODs, followed by E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(31-575), E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-TAT-SP-PtNTT2 and E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2.

Table (3): Final OD600 of all cultures.

The highest OD600 was reached by the wildtype E. coli BL21(DE3) with 5,487 ± 0.038, the lowest by E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2 with 1.623 ± 0.481.

| Strain | Final OD600 [-] | |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | 5.487 ± 0.038 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PtNTT2 | 4.337 ± 0.010 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2 | 1.623 ± 0.481 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(66-575) | 4.035 ± 0.051 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(31-575) | 3.865 ± 0.008 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-pelB-SP-PtNTT2 | 4.110 ± 0.005 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-TAT-SP-PtNTT2 | 2.280 ± 0.337 |

Figure (5): Graphical determination of the maximum specific growth rate µmax for the microcultivations.

Table (4): Maximum specific growth rate and minimum doubling time for all cultures cultivated in 12 well plates.

| Strain | µmax [h-1] | td [h] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | 1.059 ± 0.143 | 0.655 ± 0.135 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PtNTT2 | 1.016 ± 0.133 | 0.682 ± 0.131 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2 | 0.829 ± 0.071 | 0.836 ± 0.086 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(66-575) | 1.023 ± 0.105 | 0.678 ± 0.103 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(31-575) | 1.021 ± 0.096 | 0.679 ± 0.094 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-pelB-SP-PtNTT2 | 1.047 ± 0.097 | 0.662 ± 0.093 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-TAT-SP-PtNTT2 | 0.924 ± 0.113 | 0.750 ± 0.122 |

Figure (6): Microcultivation in a 96 well plate performed by iGEM team UNIFI from Florence, Italy.

E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2 and E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(66-575) were cultivated in a total volume of 3 mL at 37 °C and 130 rpm. The growth difference between the two strains observed in previous cultivations could also be observed in this experiment carried out by the team from Florence. E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2 reached a final OD600 of 0.329 ± 0.037 while E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(66-575) reached a final OD600 of 0.664 ± 0.033.

Figure (7): Graphical determination of the maximum specific growth rates for the cultivations carried out in 96 well plates by the iGEM team UNIFI.

Table (4): Maximum specific growth rate and minimum doubling time for all cultures cultivated in 12 well plates.

| Strain | µmax [h-1] | td [h] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | 0.042 ± 0.004 | 16.504 ± 0.095 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PtNTT2 | 0.110 ± 0.002 | 6.301 ± 0.018 |

Figure (8): Cultivation of all transporter variants in MOPS media with K2HPO4 acting as the sole phosphate source.

The cultivation was carried out in 12 well plates and three biological replicates were cultivated of each strain. For measurement of the optical density at 600 nm, three technical replicates were taken.

Figure (9): Cultivation of all strains in MOPS media with 1 mM ATP acting as the sole phosphate source.

Three biological replicates were cultivated and three technical replicates measured for each time point.

Table (5): Final OD600 values for all cultivations carried out in MOPS media with 1,32 mM K2HPO4.

| Strain | Final OD600, K2HPO4 [-] | Final OD600, ATP [-] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | 2.923 ± 0.028 | 4.967 ± 0.143 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PtNTT2 | 3.507 ± 0.048 | 3.673 ± 0.091 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2 | 1.537 ± 0.045 | 3.033 ± 0.028 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(66-575) | 3.560 ± 0.011 | 3.347 ± 0.032 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(31-575) | 3.797 ± 0.065 | 3.580 ± 0.006 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-pelB-SP-PtNTT2 | 3.907 ± 0.018 | 3.710 ± 0.177 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-TAT-SP-PtNTT2 | 3.307 ± 0.029 | 2.177 ± 0.007 |

Figure (10): Graphical determination of the maximum specific growth rates for all cultures cultivated in MOPS media with 1.32 mM K2HPO4.

Table (6): Maximum specific growth rates and minimal doubling times of the cultivations in MOPS media with 1.32 mM K2HPO4.

| Strain | µmax [h-1] | td [h] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | 0.444 ± 0.053 | 1.561 ± 0.199 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PtNTT2 | 0.499 ± 0.050 | 1.389 ± 0.100 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2 | 0.385 ± 0.044 | 1.800 ± 0.114 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(66-575) | 0,568 ± 0.057 | 1.220 ± 0.100 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(31-575) | 0.532 ± 0.022 | 1.303 ± 0.041 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-pelB-SP-PtNTT2 | 0.549 ± 0.017 | 1.263 ± 0.031 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-TAT-SP-PtNTT2 | 0.463 ± 0.028 | 1.497 ± 0.060 |

Figure (11): Graphical determination of the maximum specific growth rates of all cultivations performed in MOPS media and 1 mM ATP.

Table (7): Maximum specific growth rates and minimal doubling times of the cultivations in MOPS media with 1 mM ATP.

| Strain | µmax [h-1] | td [h] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | 0.673 ± 0.012 | 1.030 ± 0.018 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PtNTT2 | 0.600 ± 0.021 | 1.155 ± 0.035 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2 | 0.463 ± 0.035 | 1.497 ± 0.076 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(66-575) | 0.644 ± 0.069 | 1.076 ± 0.107 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(31-575) | 0.428 ± 0.091 | 1.620 ± 0.213 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-pelB-SP-PtNTT2 | 0.518 ± 0.043 | 1.338 ± 0.083 | |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-TAT-SP-PtNTT2 | 0.334 ± 0.047 | 2.075 ± 0.141 |

Figure (12): Relative beneficial effect of the different PtNTT2 variants.

As expected, the native transporter variant shows the highest positive effect since it most likely also exhibits the highest activity. Surprisingly, the two truncated versions show a higher effect than the versions with a pelB and TAT signal peptide.

Figure (13): Confocal laser scanning microscopy of the different PtNTT2 variants fused to GFP (BBa_E0040).

The pictures were taken with 100x magnification and show from A to E: E. coli BL21(DE3), E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PtNTT2, E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2, E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(66-575), E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-PtNTT2(31-575), E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-pelB-SP-PtNTT2 and E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PlacUV5-TAT-SP-PtNTT2.

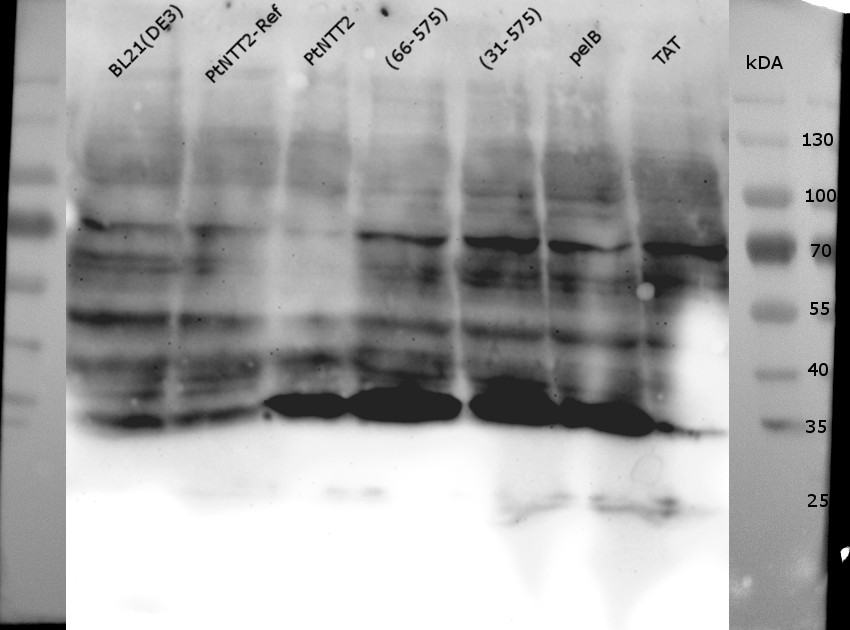

Figure (13): SDS-PAGE of the GFP-fusion constructs of PtNTT2

The cells were prepared using the fast cell lysis for SDS PAGE protocol. E. coli BL21(DE3) and E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PtNTT2 were used as negative controls. Unsurprisingly, no thick band can be observed around 90.3 kDa, which would be the size of PtNTT2-cMyc-GFP. No bands can be observed for the other PtNTT2 variants.

Figure (14): Western Blot of the samples prepared using the fast cell lysis for SDS PAGE protocol.

An anti-GFP antibody was used for the detection of PtNTT2-cMyc-GFP variants. E . coli BL21(DE3) and E. coli BL21(DE3) pSB1C3-PtNTT2 were used as negative controls. Much unspecific binding of the anti-GFP antibody could be observed, which is not surprising given that the entire proteome of the cells was analyzed. Thick band can be observed for PtNTT2-cMyc-GFP, PtNTT2(66-575)-cMyc-GFP, PtNTT2(31-575)-cMyc-GFP and PtNTT2(pelB)-cMyc-GFP around 35 kDa. This indicates that only the cMyc-GFP linker was detected and that the linker might be cleaved of from PtNTT2 due to the high difference in hydrophobicity.

Figure (15): SDS PAGE performed with the isolated membrane fractions.

The cMyc-GFP fusion proteins were used, which should be visible around ~90 kDa, differing slightly based on the PtNTT2 variant used. No bands could be observed around 90 kDa, which was subsequently proofed by performing a western blot.

Figure (16): Western Blot of the isolated membrane fractions of the strains expressing the cMyc-GFP fusion proteins.

Thick bands can be observed around 28 kDa for all samples except for PtNTT2-cMyc-GFP with a TAT signal peptide. The negative controls do not show the same band, but some unspecific binding of the anti-GFP antibody could be observed. Compared to the previous western blot, unspecific binding was significantly reduced. These results indicate, that the linker is most likely separated from the transporter either during the isolation process or already within the cell. This would be no surprise, given that the transporter is highly hydrophobic while the linker is hydrophilic.

Figure (17): Western Blot of the isolated membrane fraction using an anti-cMyc antibody.

Again, fragments can be observed around 35 kDa for all samples except for PtNTT2-cMyc-GFP with a TAT signal peptide. No bands can be observed for the full construct, but a very weak band can be seen between 55 and 70 kDa for the fusion protein of the native transporter.

Figure (18): SDS PAGE of the isolated membrane fraction without previous boiling

No thick bands can be observed around 70 kDa. Slightly above 100 kDa, bands can be observed for all PtNTT2 variants but not for the negative controls. But given that the samples ran quite different on the gel compared to the boiled samples, no definite conclusion can be drawn from this gel.