Screening

Having finished building the biosensor, we were able to efficiently determine psicose concentration. In order to demonstrate the feasibility of our project, we then needed to improve our sugar production by using our biosensor to select the best enzyme from a bank of D-psicose 3-epimerase (Dpe) mutants in order to maximize production.

Enzyme engineering currently relies on computation followed by directed mutagenesis on specific area of the protein. This maximizes the probability of improving activity for a defined number of mutants. But this approach restricts possible random conformational changes, with the potential to improve catalytic sites. But random mutagenesis requires the researcher to screen a much larger number of mutants, hence the need to use an efficient screening system, like the one we designed.

To achieve this, we first had to engineer our biosensor to allow insertion of the mutants into the vector, then construct the bank, and finally screen all the clones.

Mutant Drop Zone

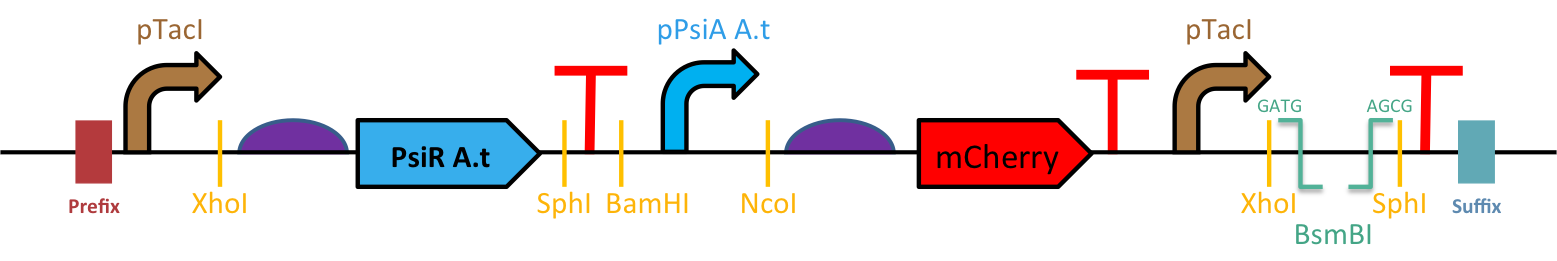

Relying on the expertise we developed on Golden Gate assembly during the course of our project, we chose to use this strategy to insert our mutants into the plasmid. For this, we engineered the Mutant Drop Zone (MDZ). This short sequence (320 bp) works following the same principles as the Universal Biosensing chassis (BBa_K2448023 or BBa_K2448024): standardized fusion sites for Golden Gate that allow quick and efficient insertion. The mutant drop zone can also be used with traditional restriction-ligation but loses its high throughput ability.

The mutant drop zone is designed to fit between the second terminator of our biosensors and the iGEM suffix (Figure 1).

Construction of the Enzyme Mutants Bank

There are many methods available to build a bank of enzymatic mutants, depending on what you are looking for. We chose to use Error Prone PCR because it favors mutations during the elongation phase, thanks to a mutagenic buffer (for example imbalance in dNTPs concentrations) and low fidelity polymerases. This technique remains more efficient than chemical methods which rely on reagents to modify the sequence and is also safer for the user, as chemical mutagens are highly toxic. Moreover, it is an a priori free method compared to saturating mutagenesis like NNK.

To build the bank of D-psicose 3-epimerase from C. cellulolyticum (BBa_K2448021) mutants, we used the protocol described by Wilson & Keefe [1]. This PCR has been performed on C. cellulolyticum Dpe gBlocks provided by IDT. Using custom primers, we were able to obtain variants with a theoretical average of 8 amino acids mutated according to [1], number of cycles and length of our sequence. We also performed a high fidelity PCR on the gBlocks in order to get our positive control, the non-mutated Dpe.

We then inserted the sequences in the mutant drop zone of the Psicose biosensor pPsiA-PsiR from Agrobacterium tumefaciens (BBa_K2448025) with downstream the Mutant Drop Zone using Golden Gate assembly since BsmBI sites were present in the overhangs of the primers (Figure 2). We transformed the Golden Gate product into E. coli K12 DH5α, even though it is not a strain designed for protein expression, it’s a well-known strain and it has been used to characterize the biosensors.

Screening

The screening of the bank has been performed following the protocol described in the ‘Protocol’ session of our wiki. Essentially, we cultivated all the clones present on the plates after the transformation and used a 96 well plate along with a plate reader to measure the fluorescence in each well. All tests were performed in technical duplicates. Fluorescence measurements (mCherry) have been normalized on cell density (OD600nm). In order to best evaluate enzyme activity, we have determined the optimal concentration of inducer, here the fructose (See details on the Bioproduction Part). Therefore, all screening process have been conducted with 50 g/L of fructose per well for 9 to 10 hours as this is the optimal measurement time according to our biosensor characterization (See details on the Biosensors Part).

According to raw data, fluorescence of the positive control containing the wt Dpe (BBa_K2448035) is around 4500 arbitrary units. Biosensor characterization allowed us to correlate fluorescence and psicose concentration. Then we can estimate that psicose produced by the wt Dpe enzyme to be around 10 g/L which is coherent with measurements perform in bioproduction (See details on the Bioproduction Part).

Figure 3 presents the outcome of our screening process. The most important observation is that 6 mutants showed an activity superior to the positive control, with 2 of them displaying more then 30% increase of psicose production. This represents 1,5% of the bank population, which is a very promising rate. As expected, the majority of the clones carry mutants with relatively low activity compared to wt Dpe, most of them showing an activity between 10 to 25% of wt and 46 clones exhibiting at least 75% of wt activity.

The results in Figure 3 show that our screening process works under realistic conditions. Indeed, the biosensor we developed is able to give accurate assessment of the psicose production on positive control clones carrying the wild-type enzyme, but also on bacteria carrying mutant versions of Dpe. This screening process also allowed us to screen around 400 mutants and discover at least 2 enzymes with potentially improved activity according to the fluorescence data.

Perspectives

Short Term Perspectives

From this point, we should recover the plasmid in order to sequence the mutant enzymes, and extract the sequence by PCR to put it in an expression vector. This would allow us to thoroughly assess its activity (See details on the Bioproduction Part).

Longer Term Perspectives

In order to bring this process to its full potential a much larger number of clones would be required to be screened. There are also other possibilities to improve on the process. First, this process could be strongly improved with the use of a flow-cytometer in order to quickly and efficiently sort the cells depending on their fluorescence. The use of such a device would empower this protein engineering method and make it high throughput. Then, running through more cycles of screening and bioproduction, to improve the D-Psicose 3-epimerase, would allow us to select mutants with higher activity, reaching unprecedented biocatalysis yields.

Finally, the whole method could be transferred and applied to improve any enzyme harnessing the power of the UBC. Thus enabling the quick assembly of a biosensor able to detect, directly or indirectly, the compound of interest, whether it’s a reaction product or a substrate.

References

- [1] Wilson DS, Keefe AD. Random Mutagenesis by PCR. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology (2001) 51, 8.3.