DEMONSTRATE

Remember to celebrate milestones as you prepare for the road ahead

- Nelson Mandela

In the given time frame, we achieved important milestones that will pave the long way that is ahead of us for the successful development of the Key. coli system.

1. Promoter library with a wide expression range

We employed 5 different promoters previously tested in E. coli (p1-5), alongside a promoter sequence with modified TATA boxes (pE) that would serve as a negative control. These were combined with strong and weak versions of suitable ribosome binding sites, expanding the library to 12 possible expression signals. The promoter library was tested with RFP.

The expression signals employed yielded different degrees of fluorescence, spanning a wide range over all time points assayed. The wide expression range is an advantage for the Key. coli system, introducing a desired degree of variability.

In future embodiments of the Key. coli system, the promoter library can be further expanded to include more expression signals with the aim of pushing the boundaries of the expression range observed here even further.

2. sgRNA-promoter pairs with varying repression efficiencies

We employed 5 different sgRNAs (sgRNA1-5) with SEED sequences complementary to the chosen promoters (p1-5) and a sgRNA0 used as a control, unable to target any of the five selected promoters nor the E. coli genome.

We demonstrated that dCas9 RNA interference is feasible, efficient and specific as the constitutive expression of both dCas9 and each of the tested sgRNAs led to loss of the red colouration of colonies on the plate or reduction of red fluorescence in liquid culture; this is a qualitative proof of effective interference in RFP transcription.

Nevertheless the degree of interference was different between different sgRNAs. As expected, there was no significant transcription interference when each sgRNA was combined with the null promoter pE, suggesting that the interference is specific to the target region. Interference was also quantified with a fluorescence assay.

The combined use of promoters of different strengths and sgRNAs of varying repression efficiencies has generated a greater range of expression profiles.

The proof-of-concept of CRISPR interference demonstrated here allows us to envision its permanent incorporation in the Key. coli system, which could even include a further expansion of the sgRNA pool.

3. Random plasmid assembly via ligation is a feasible strategy

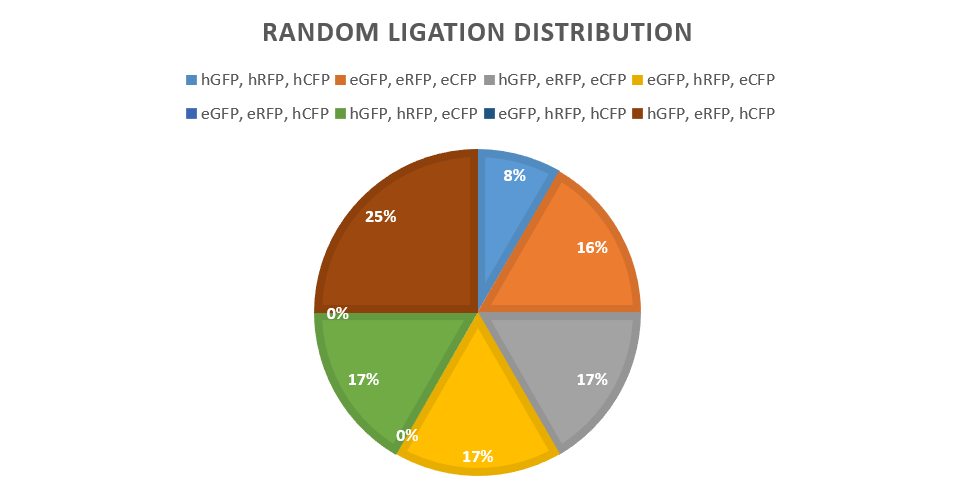

The degree of randomness that can be achieved from a ligation reaction was put to the test in order to assess the suitability of this technique for the large scale generation of keys.

A strong and weak promoter was combined with all three fluorescent reporters: GFP, RFP and CFP. Ligations were carried out with controlled use of the DCBA restriction system, with the positions that each reporter could assume being predetermined. In theory, under this design, 23 possible versions of a ligated plasmid could be obtained. From a sample size of 12 colonies, 6/8 combinations were encountered with comparable distribution frequencies. It is logical to assume that upon screening a larger colony sample, all possible combinations could be encountered.

The above results provide strong evidence that assembly via ligation can generate a truly random combination set, thus being a suitable method for key generation in the future. Scaling-up the random ligation process would be possible with larger part pools, supported by the increasing availability of robotic platforms and relevant high-throughput, automated protocols for plasmid assembly, bacterial transformation, colony picking and screening.

4. Freeze-drying is a suitable storage method that allows reproducible revival and expression output

Two engineered E. coli strains expressing RFP under strong or weak promoters were cultured, aliquoted and freeze-dried. These aliquots were then split in three subgroups relative to their storage environment: -80°C, 4°C and room temperature (RT). At frequent and regular times, cells were revived in liquid medium. OD and fluorescence measurements were performed to assess the growth and fluorescence profile for each sample.

The results show that storage temperature does not have a significant impact on revival quality up to 2 weeks of storage. At 3 weeks however, the expression profile of samples stored at RT begins to deviate. Longer-term experiments would be able to provide more accurate information.

Based on the current data, -20oC would be a suitable storage temperature for the Key. coli device ensuring consistency of the expression output. Most importantly, this temperature is easily achieved using a conventional freezer.

Expression output is identifiable from 2-hrs onwards, implying that the system can also be used with a very small time delay, in cases where time is of essence. However, for more accurate use, we recommend that the ‘unlock’ attempt should take place from 4-hrs onwards.

Growth and expression profiles obtained elsewhere (e.g. Groningen) were also comparable to the ones obtained in Nottingham, pointing towards the potential universality of the >i>Key. coli system.

5. Modelling and software programs underpinning Key. coli

To support the work done by the wet team, diverse and complementary models were developed.

First, constitutive gene expression was modeled to set the basis of protein synthesis in a bacterial cell. Then, CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) was superposed to this basic model by introducing different parameters such as dCas9 production rate and dCas9:gRNA association rate, simulating transcription interference on the expression of one, two or i fluorescent proteins (FPs). A third layer of modelisation linked the maximum expected fluorescence to the protein concentration available, allowing access to the latter directly via spectrophotometric measurements.

As fluorescence was at the heart of our project, an absorption and emission model summarised all useful values that could be used to excite and detect emission from each of the three selected FPs.

In addition to the above, a software was developed to assess fluorescence levels between Key. coli capsules and the mother strain. The software is able to translate spectrophotometric readings into image-like data using an image similarity algorithm, with predefined threshold values. Readings outside of the threshold range would result in “Denied Access” to the lock of interest.

Finally, we have generated a Random Number Generation tool and a user-friendly Excel sheet with editable Protein Concentration fields that can be used to create a customised strain and get the associated tweaked combination allowing for randomness and flexibility.

Conclusion

In this study we have shown the first steps taken towards the development of a randomly assorting, fluorescent bacterial key: the Key. coli. The results of the proof-of-concept experiments undertaken provide us with confidence that Key. coli, albeit futuristic, is a feasible technology employing available know-how, such as large part pools, random plasmid assemblies and CRISPR interference. In addition to proving the scientific feasibility of Key. coli, we have also designed a safe and portable device for its storage and revival at a desired time point. Finally, we have paired Key. coli to a streamlined authentication procedure, tailored to be immune to current hacking frameworks.

We hope that this next generation biological security system will one day be commercialised so we can all protect our gems with germs! Until then, there is lots of exciting work to be done by team UNOTT...