Template loop detected: Template:HFLS H2Z Hangzhou<!DOCTYPE html>

Performance

Overview

While we reached the fact that both NOR and nosZ react at much faster rate than NiR which is crucial to the substrate channeling system, we cannot guarantee that no biotoxin (NO and N2O, the intermediate product of reaction pathway) will escape during the reaction pathway if we simply expressed the separately using different RBS.To give a better view of the issue, we compared the pros and cons of different ways to create this substrate channeling system.

Separately express target enzymes using different RBS

Pros

1 |

easy to construct |

2 |

use the RBS of different efficiency to regulate the expression |

Cons

1 |

Enzymes can be far apart in space, resulting in bad efficiency |

2 |

possible leakage of bio toxins |

Fusion Protein

Pros

1 |

The product of previous enzyme will directly go to active site of next enzyme |

2 |

Enzymes are physically fixed next to each other, kinetics of the fusion protein is easy to predict |

Cons

1 |

difficult to construct |

2 |

difficult to select the correct linker |

3 |

not possible to regulate the ratio of expression of three enzymes |

Scaffold method

Pros

1 |

possible to regulate expression ratio |

2 |

fixed physical positions for enzymes |

Cons

1 |

most difficult to construct |

However, in our situation, the difference between Scaffolding and Fusion Protein is quite small: since NiR's reaction rate is already a limiting factor in the pathway, there is no need to regulate the expression ratio between our target enzymes. So we settled down with fusion protein.

Background

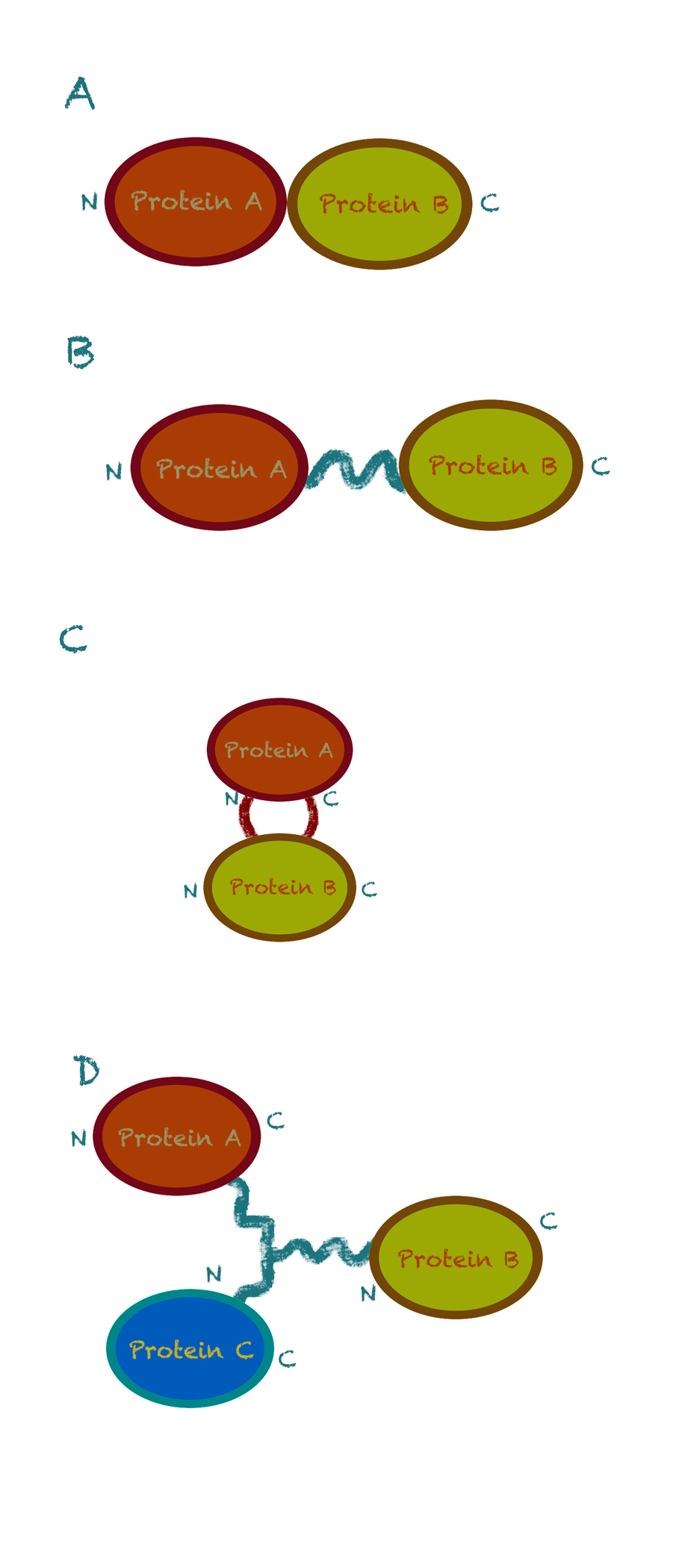

There are currently four methods of fusion protein assembly:1 |

End-to end fusion. This method works by directly add the gene for the second enzyme to the end of gene for the first enzyme (the stop codon of the first gene is removed). The N-terminus of one domain is linked to the C-terminus of the other domain. However, the error rate of this method is relatively high, due to the uncontrollable interactions of amino acid residues and errors during the folding of polypeptides. |

2 |

End-to-end fusion with a linker. This is an improvement on the previous method, as the linker protein separates the domains of a bifunctional fusion protein, preventing the domains from interacting and interfering with each other. This method has been successfully applied in many researches. |

3 |

Insertional fusion. In this method, one domain is inserted in-frame into the middle of the other parent domain. Since a double connection allows fewer degrees of freedom than any single connection, insertional fusion proteins are expected to form more rigid and stable structures than end to end fusion proteins. However, the construction is much more complicated because it requires precise information on the parent domain structure to identify a suitable insertion site. |

4 |

Branched fusion. Instead of fusion at gene level, branched fusion works by directly fusion at protein level usually using enzymes. This method avoids problems of gene expression and folding of protein, but there are many limitations about the design of the linker. |

Fig 1. Four strategies for fusion enzyme design. (A) Direct end-to-end fusion. (B) End-to-end fusion with a linker. (C) Insertional fusion. (D) Branched fusion (N and C denote the N-terminus and C-terminus of the protein, respectively). [1]

We take the advantages and disadvantages of each method into serious consideration. Since we currently do not have the knowledge and ability to analyze the domains of proteins, and complicated intersectional fusion is beyond our level, we choose the second method, end-to-end fusion with linkers.

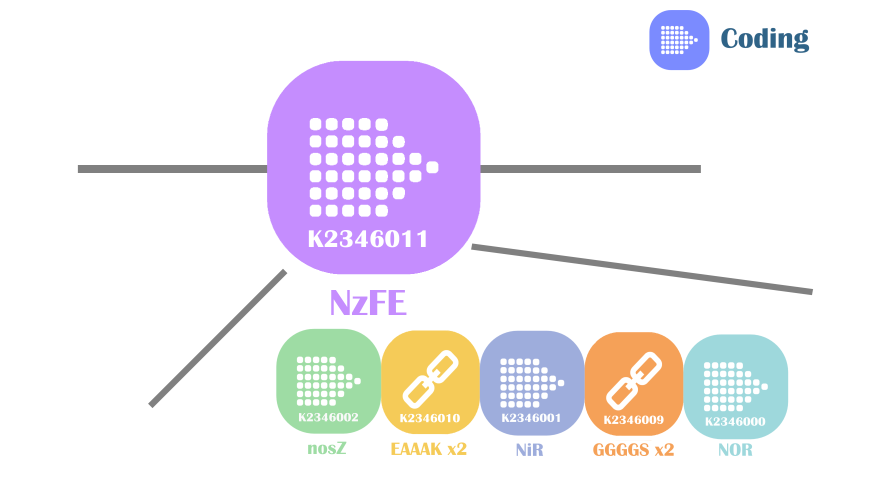

Linker Selection

Our fusion protein NzFE (nitrite reducing fusion enzyme) is constructed using GGGGS x2 linker and EAAAK x2 linker. The reason for this selection is simple: these two linkers are best characterized. GGGGS x2 linker is a flexible linker with advantages like improving protein solubility, providing enzyme flexibility for catalysis, domain separation. EAAAK x2 linker is an α-helix forming linker, has advantages of improving protein solubility, providing enzyme flexibility for catalysis and maintain domain separation. The share advantages of these two linkers are they provide good domain separation, crucial for maintaining the structures of original active sites in our fusion protein.

Fig 2. Construct of our fusion enzyme

Enzyme CDS Placement

At first glance, our fusion enzyme design may seemed counter-intuition for you: we placed the CDS for first enzyme of our substrate channeling device in the exact middle of the construct, instead of front. We did this actually to make sure the linker selection will greatly affects the reactivity of our fusion enzyme: if the linker selection is not wise, we would detect no reactivity of fusion enzyme at all. Placing nitrite reductase in the middle of the construct ensures that if the fusion enzyme can reduce nitrite ions from the solution, we can make the educated inference that the active sites of nitric oxide reductase and nitrous oxide reductase are functional.This design is due to the limited assay method for enzyme reactivity and we want to make sure our product will not release any toxic materials during use.

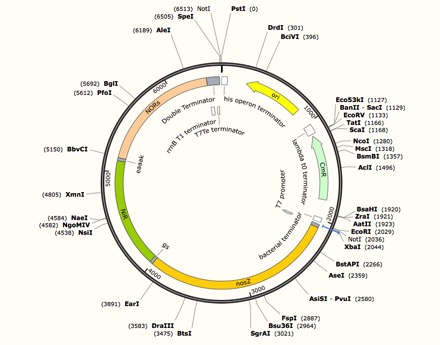

Construct Expression vector for NzFE

We used inFusion Assembly to construct this final vector. First we use PCR to eliminate the start codons for NiR and NOR, eliminate stop codons for nosZ and NiR, and adding overlap using primers. We added a T7 promoter and double terminators using PCR to complete the construction of the vector. Then we standardized the part using inFusion kit.

Expression vector for NzFE

forward primer for NOR: taatacgactcactatagggaaagaggagaaaCTGCAAATGTCAGATGATACCAAATCTCCTC

reverse primer for NOR: ccaccaccagaaccaccaccaccGGCTTTTTCCACTAACATACGACCGC

forward primer for NiR: tggtggttctggtggtggtggttctATGCTGGCAGCTCAGGTTCAG

reverse primer for NiR: TGCTGCTTCCTTTGCTGCTGCTTCGGCTTTGATAGGACCCGGAGGAC

forward primer for nosZ:AGCAAAGGAAGCAGCAGCAAAGATGGCACCTCAGCATGATTTT

reverse primer for nosZ: gcctttcgttttatttgatgcctggctctaggagcgCGACCAGATACTT

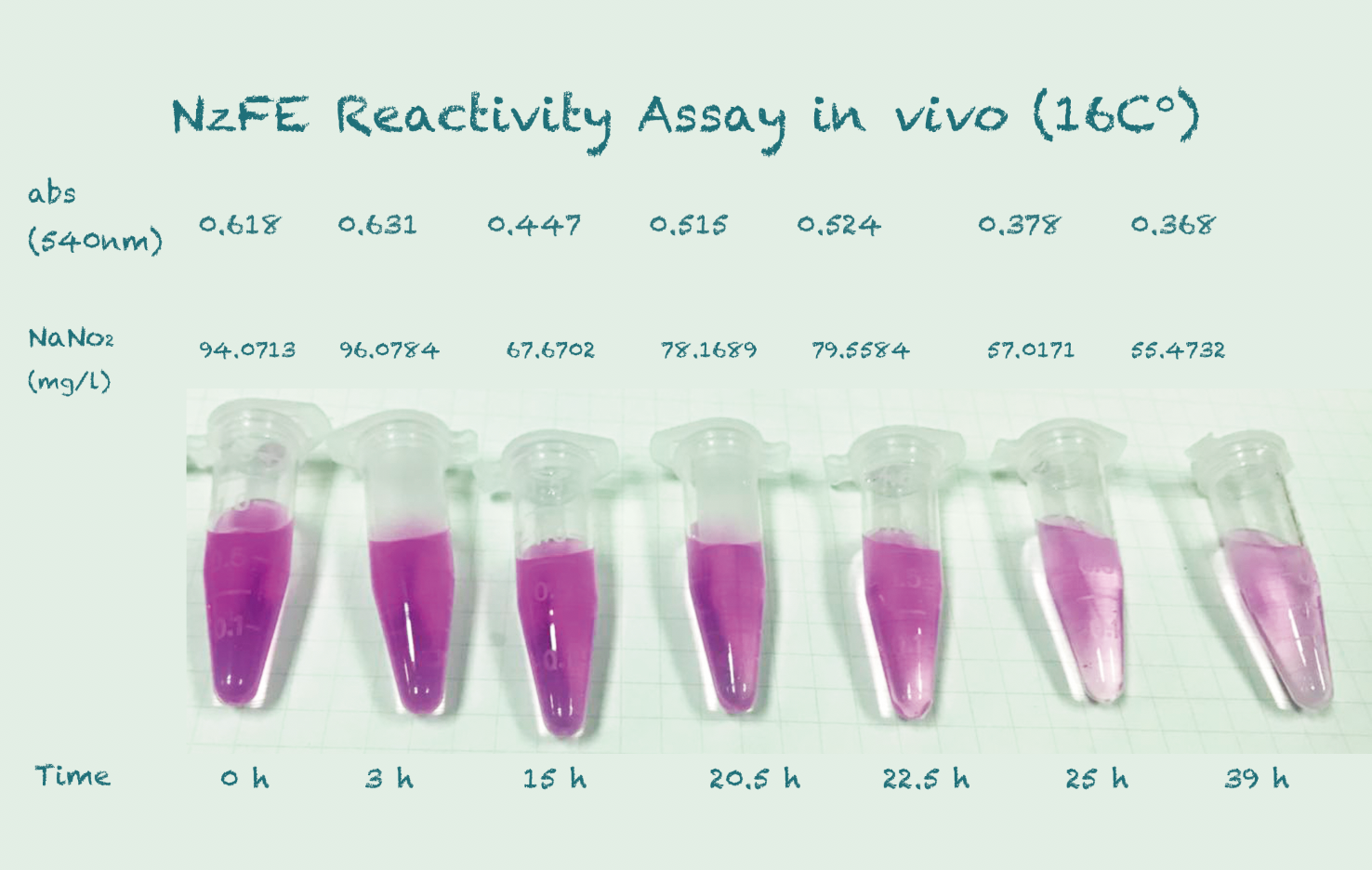

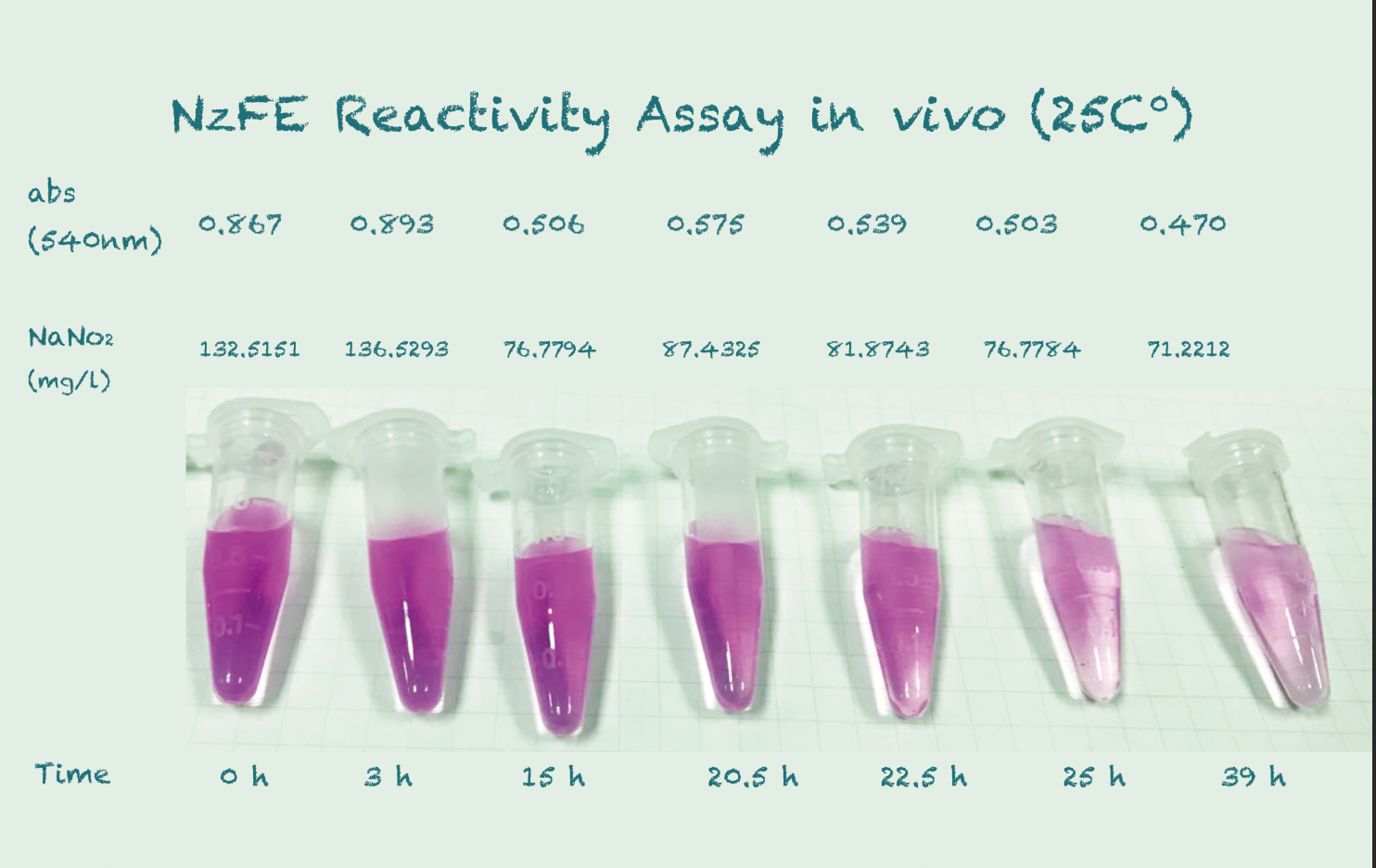

Reactivity Assay in vivo

Our fusion protein is constructed using GGGGS linker and EAAAK linker on a T7 vector. It is then expressed in $E. coli$ (BL21) under the IPTG inducer. We tested the results using the same method for NiR, which is using a chromogenic agent to show the change in concentration of nitrite. We incubated at a temperature gradient of 16, 25 and 30 degree Celsius, 220rpm.Protocol

| Add IPTG into prepared cultures of $E.coli$ (IPTG concentration: 0.1mg/L) | |

| Induce at 16 Celsius degree, 150 rpm overnight | |

| Add sodium nitrite solution and pickle extract collected from Qiumei Food (Target nitrite concentration: ~65mg/L), place three bottles of culture in different temperature | |

| Take samples (500uL) of the cultures at various time points | |

| Measure optical density(600nm) of the samples | |

| Centrifugate at 6,000 rpm for 60s | |

| Take 100uL samples from supernatant and dilute with 900uL ddH2O | |

| Take 100uL samples from the diluted solution and dilute again with 900 uL ddH2O | |

| Add 20uL of chromogenic agent to the solution | |

| Stand the solution for 20 mins and wait for the color to develop. | |

| Measure the absorbance(540nm) of the solutions | |

| Record data in Excel forms |

*Prepare the chromogenic agent as follows:

1 |

In 500mL beaker

|

||||||||

2 |

Transfer the solution to a 500mL volumetric flask and dilute with ddH2O to standard volume. |

We selected these temperature gradient because they represented the normal temperature in Qiumei Food's storage.

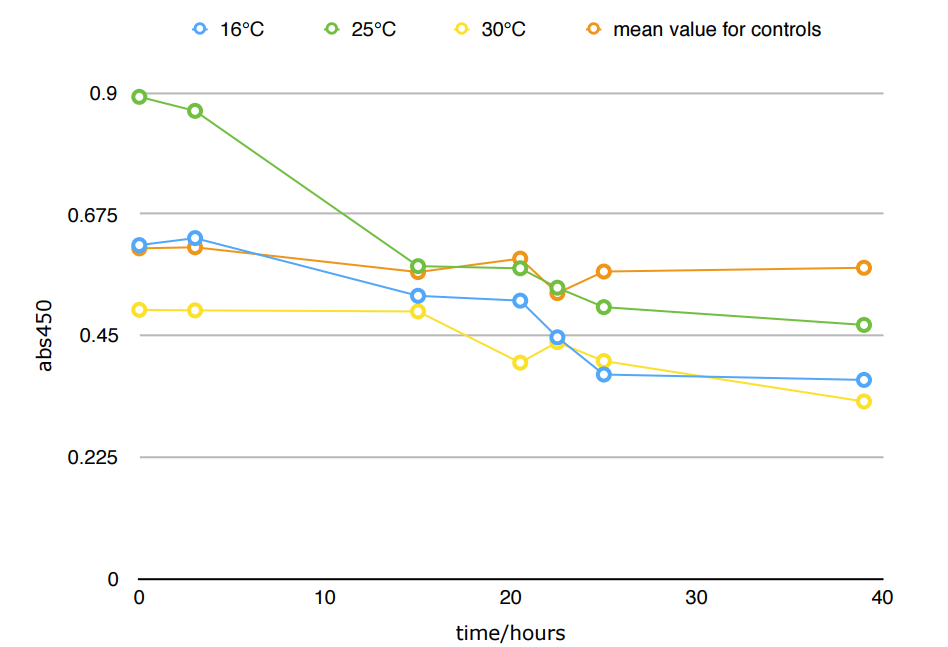

Results

*Because the controls in different temperature showed similar results, we took their mean for better presentation.

Conclusion

The difference in Nitrite concentration may be caused by the different pickle extract: Qiumei Food provided us with only small quantity of samples each package. While we are satisfied with the result of NzFE in 16 °C and 25°C: both reduced more than 40% nitrite after 39hours. However, the result of 30°C is less satisfied: only 20% nitrite reduction after 39hours. We consulted with Dr.Zhang in Bluepha, and he suggested that at 30°C, bacteria is around its optimum growth temperature compared to 16°C and 25°C, and that much higher growth rate caused too much metabolic stress on cells, leading to unsuccessful translations.Further Improvement

1 |

Implement the product by replacing better linker, making the results as close to prediction in Modeling as possible, which means finding linkers with least impact to our target enzymes' active sites. |

2 |

Testing the feedback loop device regulated by Pyear promoter(BBa_K2346005 and BBa_K2346006). |

3 |

Change our chassis to $B.substilis$(see Chassis Selection). |

Reference

1 |

Huang X, Holden H M, Raushel F M. Channeling of Substrates and Intermediates in Enzyme-Catalyzed Reactions[J]. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 2001, 70(1):149. |

2 |

[95] Nielsen KA, Tattersall DB, Jones PR, et al. Metabolon formation in dhurrin biosynthesis. Phytochemistry, 2008, 69(1): 88−98 |

3 |

Ovádi J, Srere PA. Metabolic consequences of enzyme interactions. Cell Biochem Funct, 1996, 14(4): 249−258. |

4 |

Brodelius M, Lundgren A, Mercke P, et al. Fusion of farnesyldiphosphate synthase and epi- aristolochene synthase, a sesquiterpene cyclase involved in capsidiol biosynthesis in Nicotiana tabacum. Eur J Biochem, 2002, 269(14): 3570−3577. |

5 |

Tokuhiro K, Muramatsu M, Ohto C, et al. Overproduction of geranylgeraniol by metabolically engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2009, 75(17): 5536−5543. |

6 |

Zhou YJ, Gao W, Rong QX, et al. Modular pathway engineering of diterpenoid synthases and the mevalonic acid pathway for miltiradiene production. J Am Chem Soc, 2012, 134(6): 3234−3241. |

7 |

Albertsen L. Engineering the spatial organization of metabolic pathways: a new approach for optimization of cell factories [D]. Denmark: Technical University of Denmark, 2009. |