Overview

Co-culturing of microorganisms is an extremely promising approach, in Biology, for understanding natural and synthetic cell population interactions, and for applications in Industrial Biotechnology including manufacturing and drug research. However, the maintenance of stable and productive co-cultures is technically challenging, expensive, and can be time consuming. This project's aim was to develop a Digital In-line Holographic Microscope (DIHM), along with associated software. This would be able to monitor co-culture counts in an isolated, closed system, in real time and inexpensively.

Since Digital Holographic Microscopy uses only monochromatic light to observe cells [1], it can potentially be used to analyse cultures without disturbing them, vastly reducing the chances of contamination. To achieve this, we endeavoured to create a mill-fluidic analysis chamber through which we could pump liquid cultures. The chamber would be optically flat to allow for DIHM based observation. This proposed technique avoids multiple instances of pipetting, staining and disposal of analysed samples.

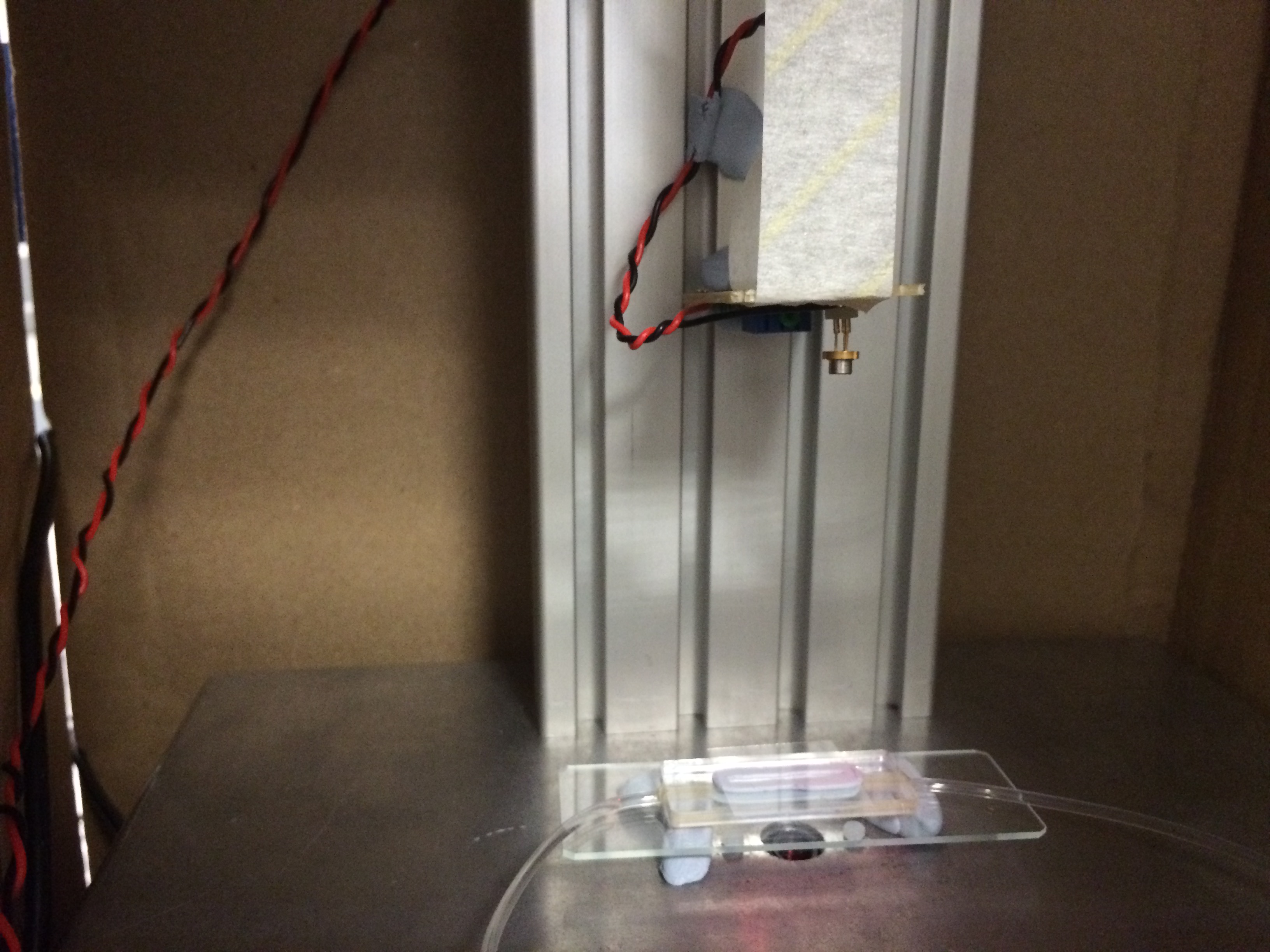

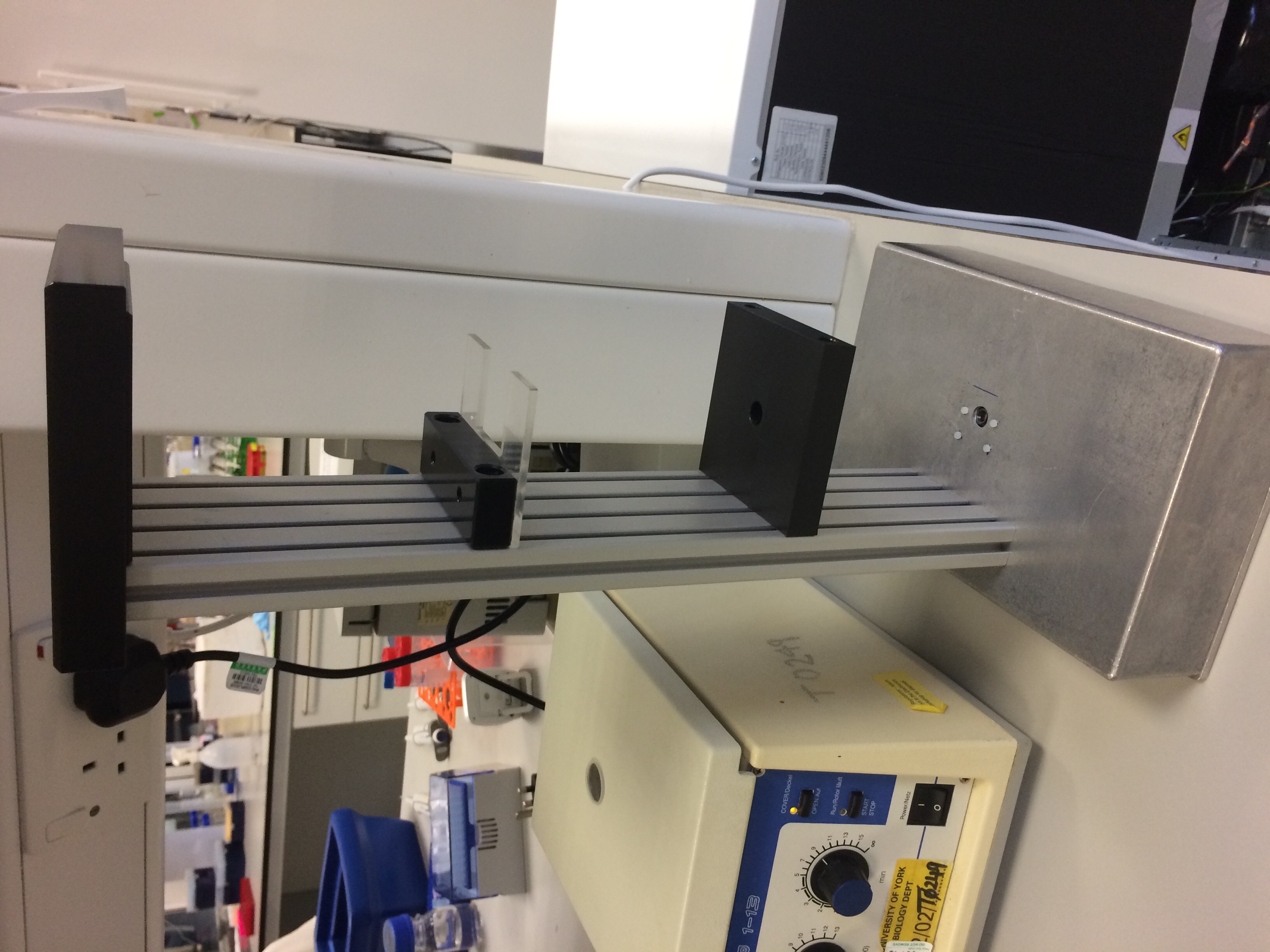

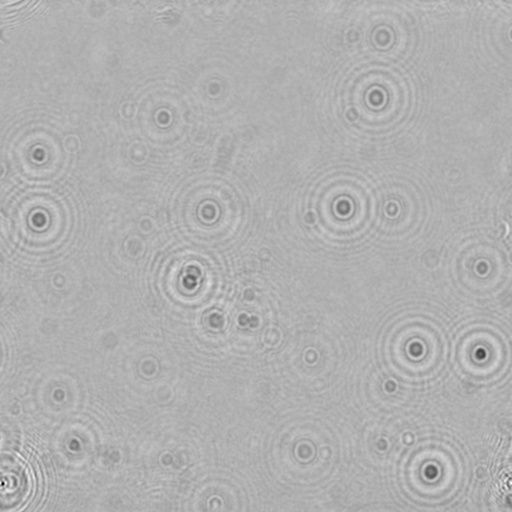

- Figure 1: Monochromatic source (laser) and milli-fluidic chamber on the DIHM (before completion of hardware).

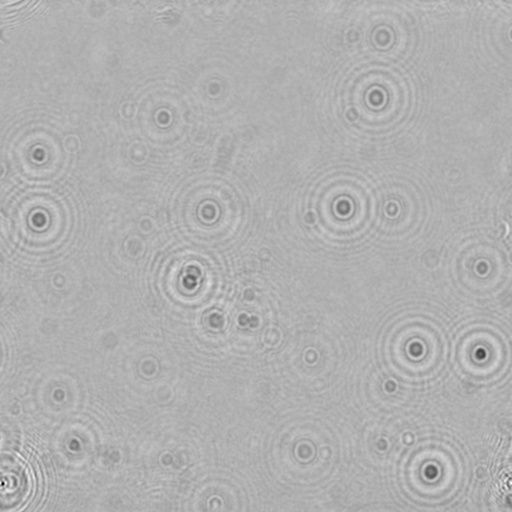

The DIHM captures an image of the diffraction pattern created by illuminated organisms and software is used to refocus the image into many 2D planes. These are stitched together in a video (a hologram) that shows the focal plane panning through a section of the sample. When an organism is in focus, its shape and size can be determined, allowing for confirmation of what is causing a given diffraction pattern. Further, by looking at the whole hologram, the number of organisms through which the focal plane passes can be counted, enabling a value of the number of cells per millilitre to be obtained. We attempted to count cells using blob-detection software which could also differentiate between sizes/shapes to obtain organism-specific cell counts, simultaneously. We also created software to ameliorate the image acquisition process.

- Figure 2: Foreground image of C. reinhardtii on glass slide.

- Figure 3: Hologram created from the image in figure 2.

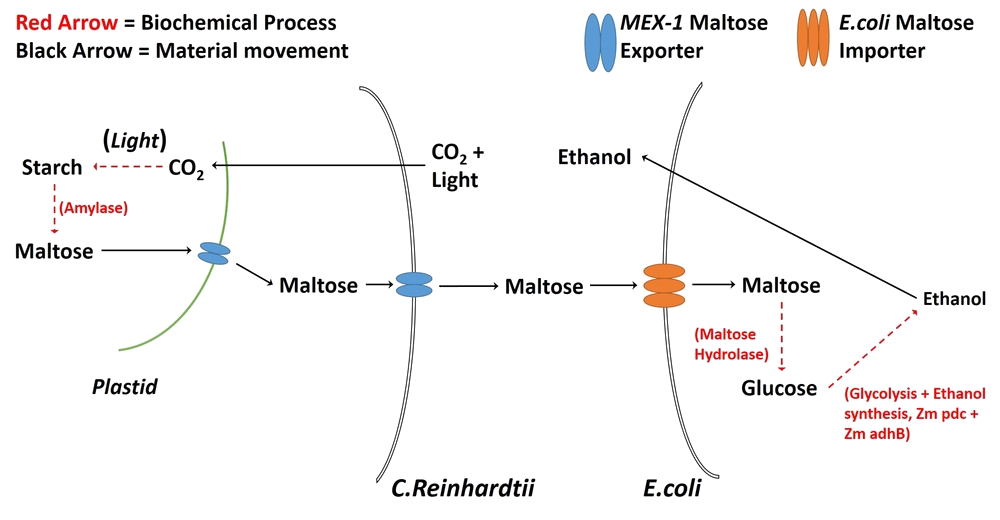

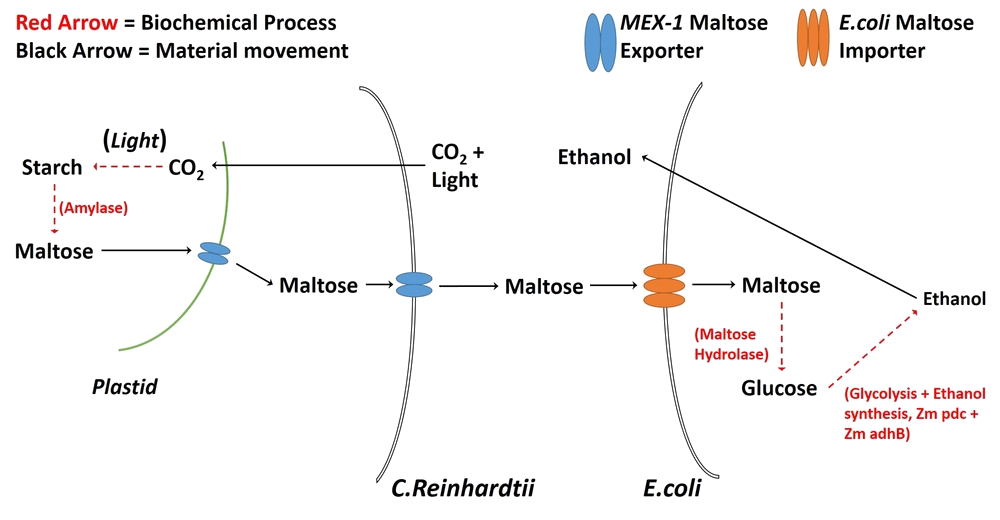

To complement the microscope, we attempted to develop a synthetic co-culture comprising Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Escherichia coli. Upon imaging with a DIHM, these are visually distinct organisms, due to their sizes and shapes [2][3]. We attempted to engineer C. reinhardtii to export maltose via the MEX-1 gene [4] as a means of feeding E. coli, creating a sustainable production platform. The strain of E. coli that we used (LW06) produces ethanol [5], which, in the interest of simplicity, would act as a placeholder for other, future products (e.g. biofuels). We believe that our DIHM and analysis methods are a promising start to streamlining the development of co-cultures for industrial and research applications.

We also considered that, since organisms are not always visually distinct, we should test the versatility of our cell counting methods by using various strains of E. coli with different rates of motility. This idea arose due to the use of DIHM in biophysics to analyse cell motion [6]. We analysed the motion of several types of E. coli by eye and tried to determine their relative speeds. This was intended as a proof of concept as the basis for future improvements to the analysis software. We suppose that it would be possible, eventually, to differentiate between cells of different speeds using software.

In the Beginning...

When the project began, we had several goals in mind.

- Modify Chlamydomonas reinhardtii via the MEX-1 gene so that it would export maltose.

- Co-culture the modified C. reinhardtii with Escherichia coli LW06 so that LW06 would render the exported maltose into ethanol.

- Model the growth of both organisms and ethanol production.

- Optimise the production of ethanol in the system by adjusting the ratio of the numbers of each organism.

- Monitor the number of each organism in a closed system via DIHM and milli-fluidic chamber (our QWACC system).

Why Digital Inline Holographic Microscopy?

Due to the inherently digital nature of this type of microscopy, software can easily be created and adapted such that the DIHM can not only count organisms but, also, differentiate between those that are distinguishable by physical appearance. Among the most important motivators of this hardware/software combination were speed of measurement (our target was the order of seconds or minute per measurement) and low costs for setup and maintenance. Further, in co-cultures wherein neither organism contains a fluorescent marker, the process of counting each type can become a rather complex endeavour. With our QWACC, however, there exists the potential for real-time counting of all physically distinct organisms within a sample.

-

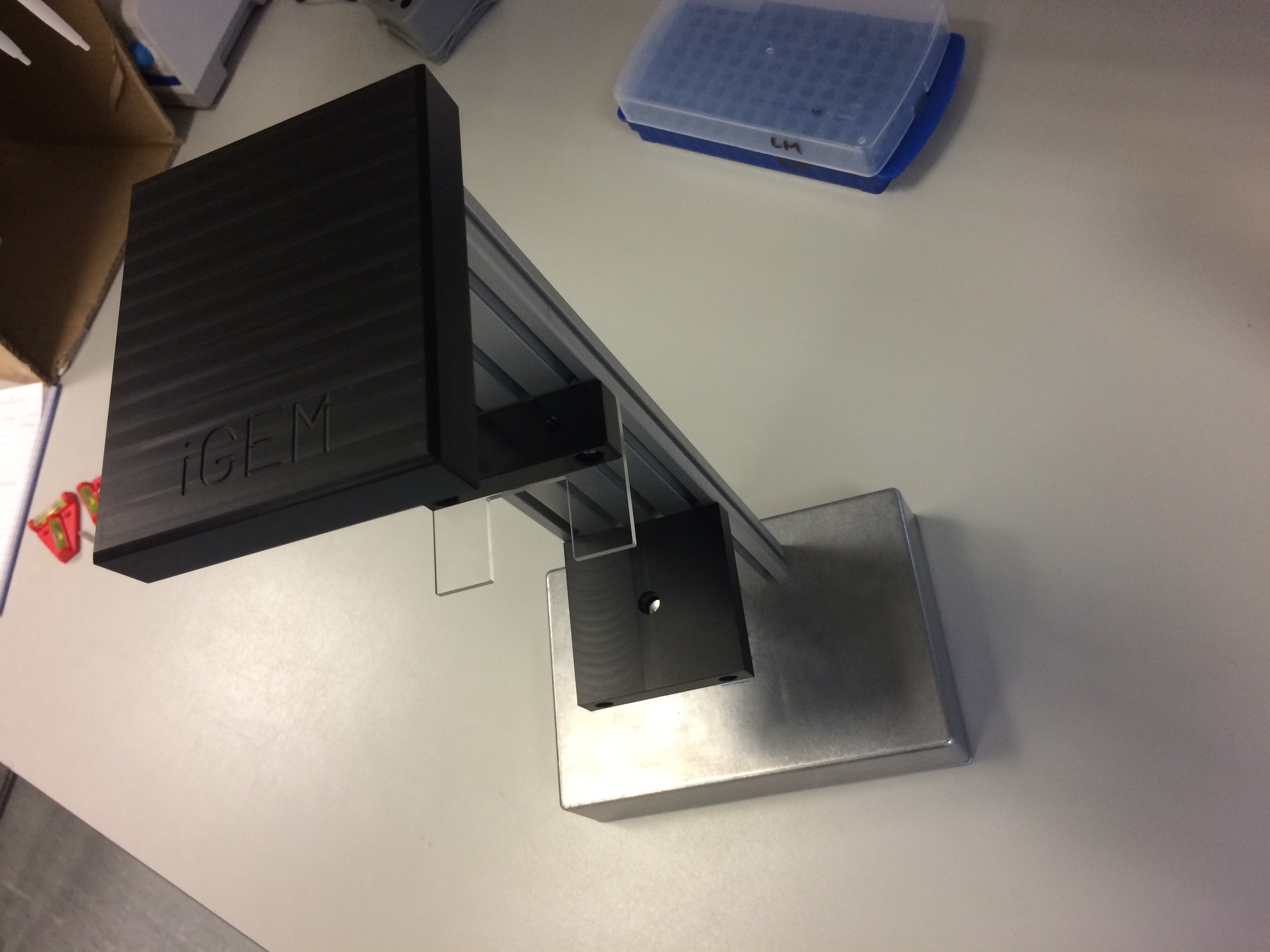

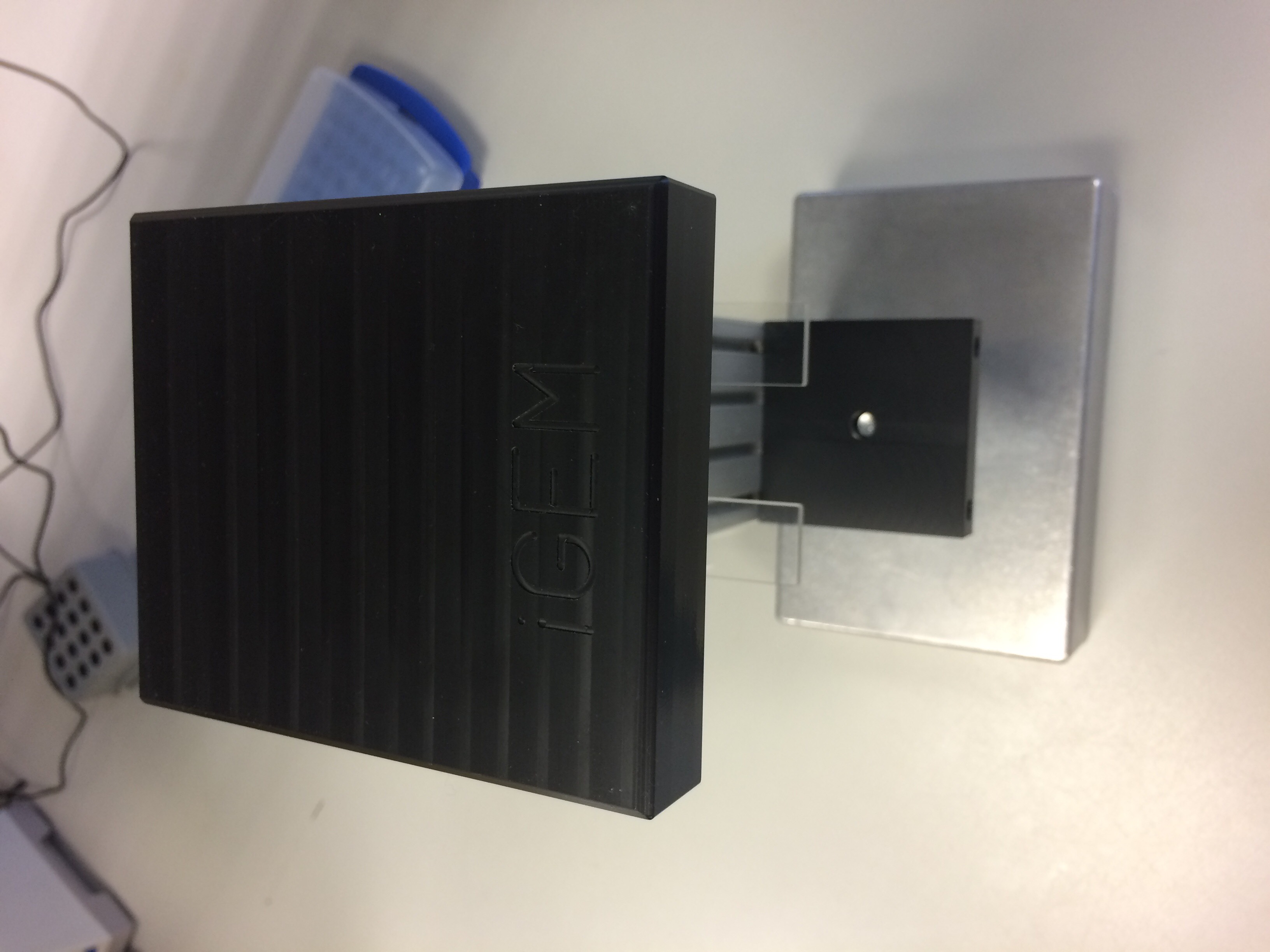

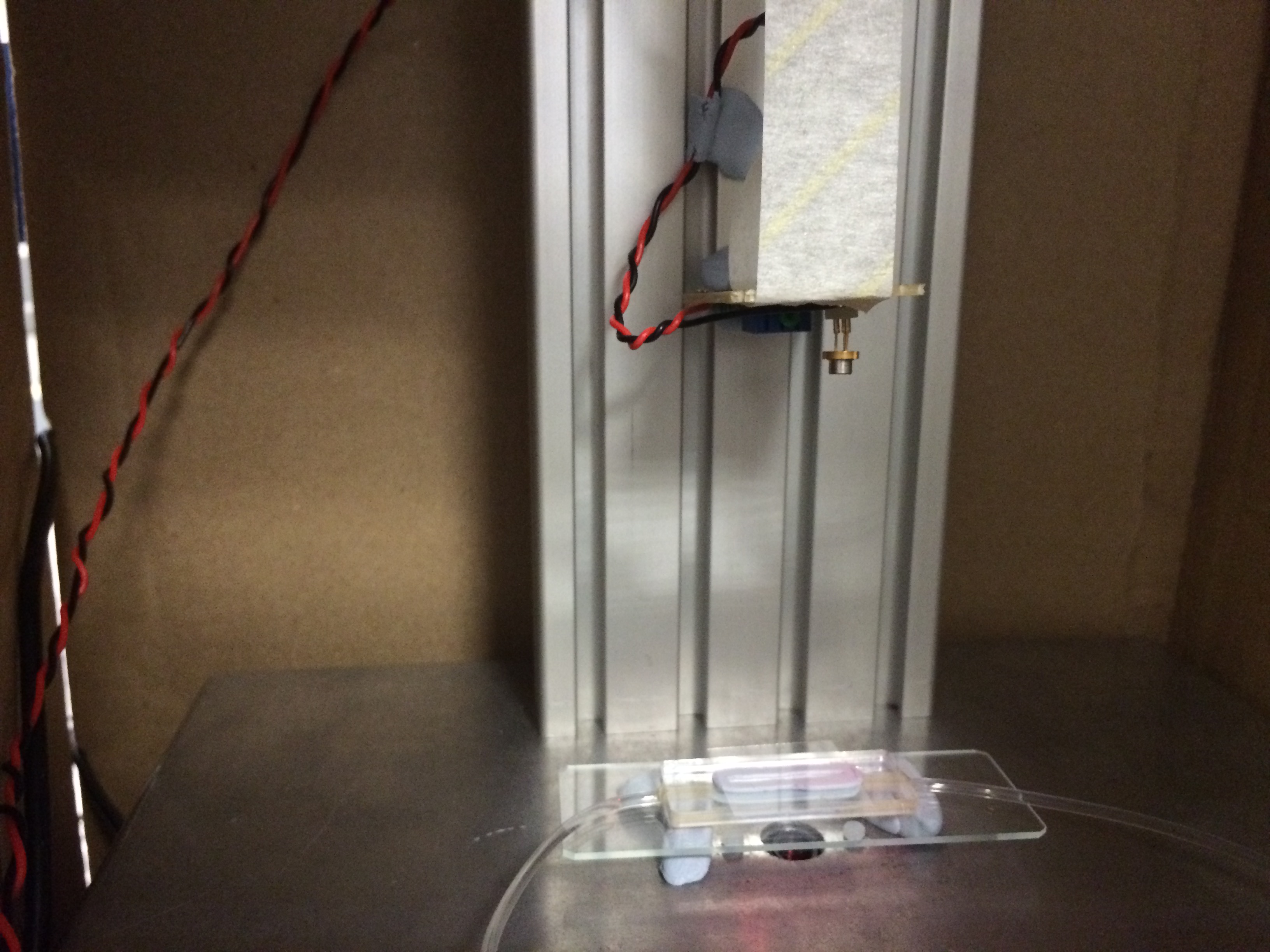

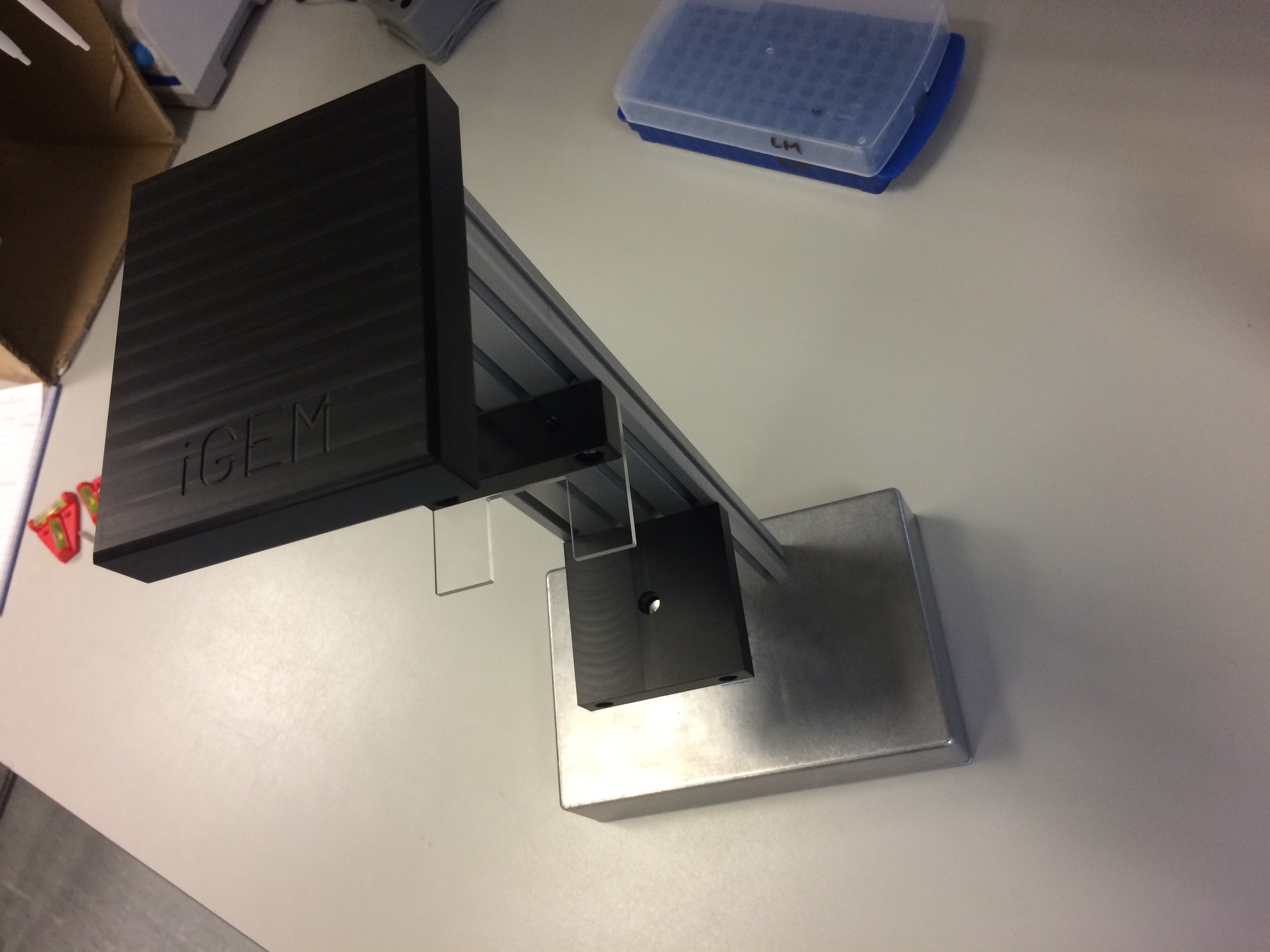

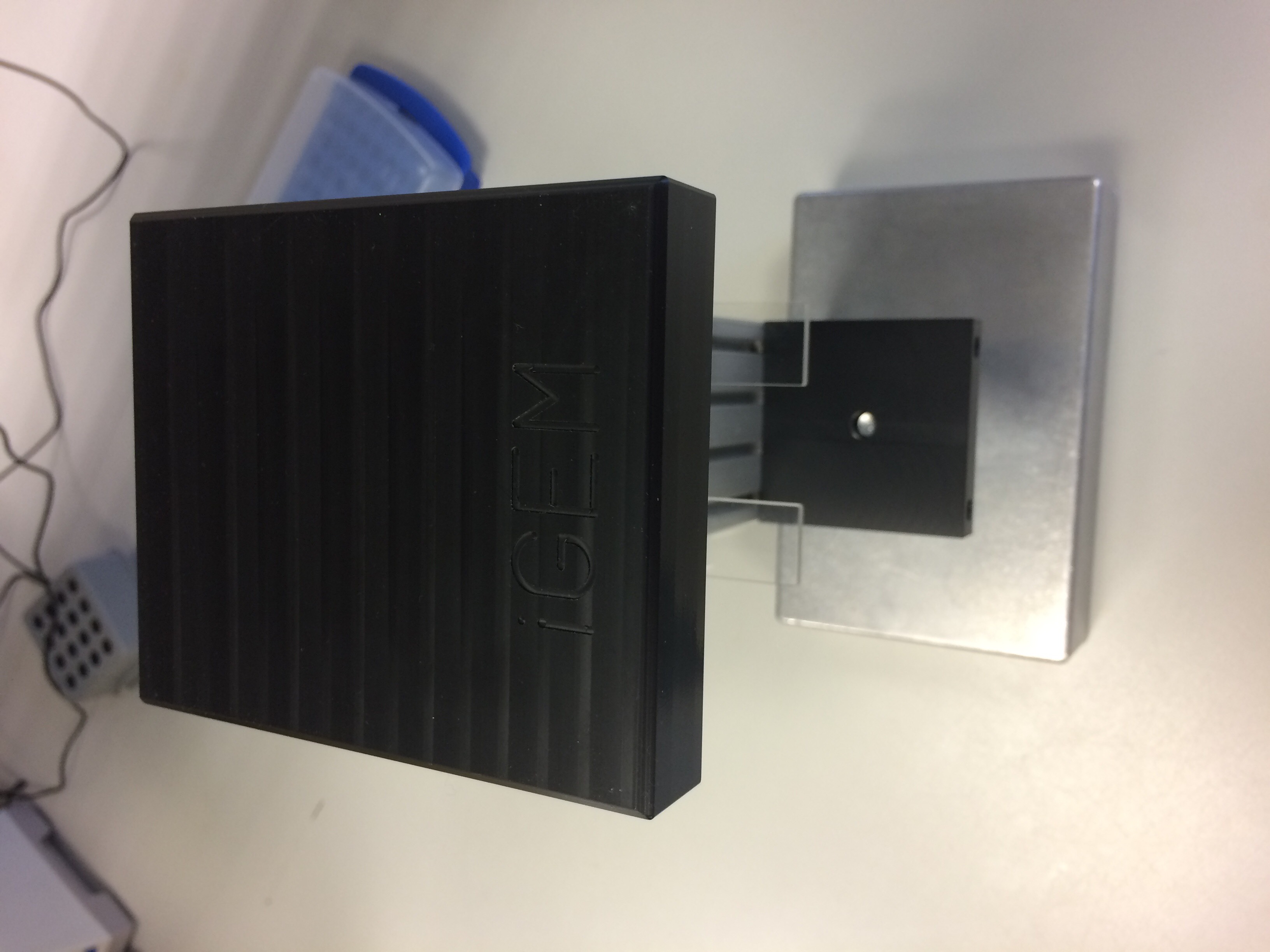

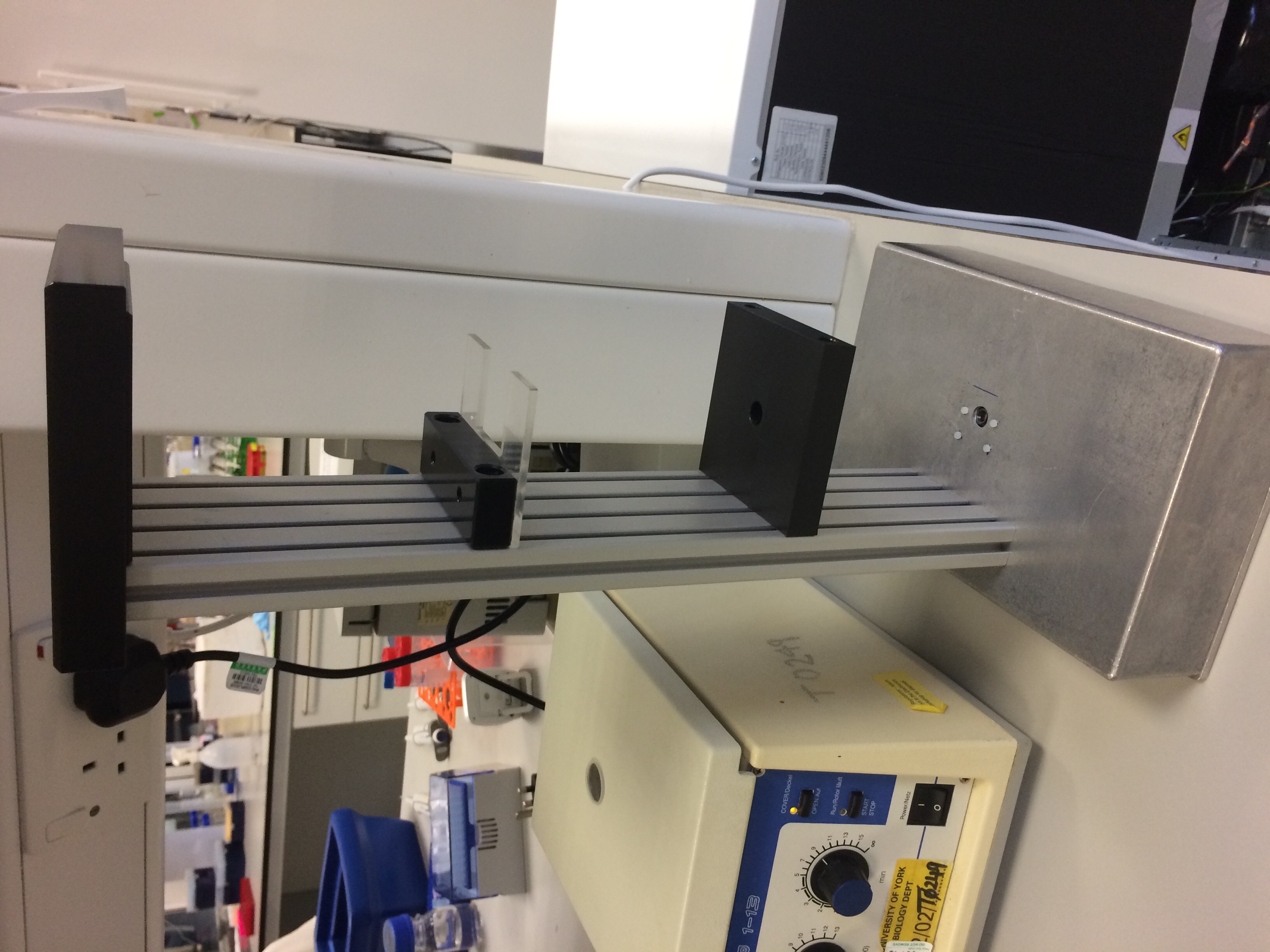

- Figure 4: The completed DIHM hardware.

In the table, below, we have compared several methods of cell counting that are able to distinguish between organisms. This is not quantitative and simply shows how each technique stacks up compared to the rest of those on the list. This is denoted through a traffic light system - green indicates that the method is desirable for the given quality, yellow corresponds to a reasonably desirable quality and red indicates that the technique is undesirable with respect to the quality.

- Table 1: A qualitative comparison of organism counting techniques. Green: desirable; yellow: reasonable; red: undesirable.

In the absence of a DIHM, the technique that we would have most likely used is flow cytometry. This would have been suitable for our needs since, in our modification of Chlamydomonas we inserted a fluorescence gene - Venus "YFP" - and E. coli also fluoresces due to mCherry. This would allow us to count the two organisms by exciting with different wavelengths and measuring the responses. This is a relatively accurate procedure and is not overly time consuming. On the other hand, it must be borne in mind that not every organism is modifiable and therefore it is not always possible to discern the numbers of organisms using this technique.

The main advantage of using the DIHM technique is its ability to differentiate between the organisms in a co-culture without need for staining or fluorescence. Albeit, this ability is limited by other factors (the organisms must either be distinguishable by shape, size or speed), but this still provides an advantage over cultures whose organisms cannot be made to fluoresce, for instance. Further, it is easily coupled with methods to create a closed analysis system - i.e. our milli-fluidic device.

Why a Milli-fluidic Chamber?

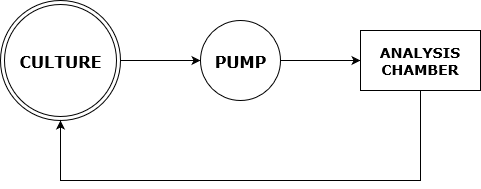

In co-culture analysis without a DIHM, most techniques involve removing a sample with a pipette, performing some preparation process to it,then analysing the sample in some manner. The acquisition of a sample from a culture in this way is an opportunity for contamination to occur. In order to remove/reduce the risk of contamination, we proposed including the inlet and outlet of a pump in the culture from inoculation onwards. The pump would be connected to our sample chamber, in a closed system, leaving no opportunity for contamination thereafter, as long as the chamber and pump were sterile to begin with.

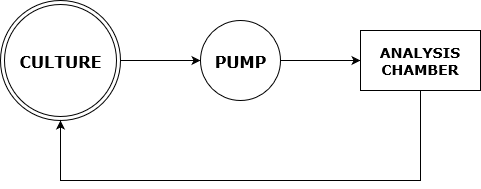

- Figure 5: Flowchart showing the path of culture samples in our proposed closed analysis system.

This also allows for automation of the analysis system through software. If the pump is on, the culture could be analysed continuously by regularly taking images of the chamber with the DIHM. These could even be used to design feedback to control the ratios of organisms in the culture for optimisation purposes.

Why Co-culturing?

Co-culturing is used in many areas of research and is promising in terms of industrial production implications [7]. Particularly interesting in our research was the potential for co-culture use in low-cost biofuel production. We noticed that co-cultures have been used to produce bioethanol [7] and so, we proposed that the process could be made less expensive by removing the need for expensive feedstocks. If an autotrophic organism were modified such that it exported sugar(s), this could be used to provide an essentially free feeding mechanism for other organisms in a co-culture. Several of the researchers at the University of York work with Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, which seemed to be well suited to be the feeder in a co-culture with ethanol-producing E. coli strain LW06. Hence, we intended to add MEX-1 into C. reinhardtii's cell membrane in order to feed LW06.

- Figure 6: A diagrammatic representation of our proposed C. reinhardtii/E. coli co-culture.

We also considered the case in which the organisms in a co-culture are not distinguishable by size or shape. We modified E. coli using the parts BBa_K777100 - BBa_K777108, from the Goettingen 2012 team's submission, to affect motility. We then tested the various modifications with the DIHM to check whether it is possible to differentiate between identical organisms with different rates of movement.

References

- [1]: H. J. Kreuzer, M. J. Jericho, I. A. Meinertzhagen and Wenbo Xu, Digital in-line holography with photons and electrons, Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter.

- [2]: E. H. Harris, The Chlamydomonas Sourcebook, 2nd Edition.

- [3]: J. H. Cummings and G. T. Macfarlane, Role of intestinal bacteria in nutrient metabolism, Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition.

- [4]: K. Fischer, The Import and Export Business in Plastids: Transport Processes across the Inner Envelope Membrane, Plant Physiology.

- [5]: L. B. A. Woodruff, Genomic engineering of Escherichia coli for improved ethanol tolerance and ethanol production, Chemical & Biological Engineering Graduate Theses & Dissertations.

- [6]: K. Thornton, R. Findlay, P. Walrad, L. Wilson, Investigating the Swimming of Microbial Pathogens Using Digital Holography, Advances in experimental medicine and biology.

- [7]: E. Park, K. Naruse, T. Kato, One-pot bioethanol production from cellulose by co-culture of Acremonium cellulolyticus and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Biotechnology for Biofuels.