| Line 296: | Line 296: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

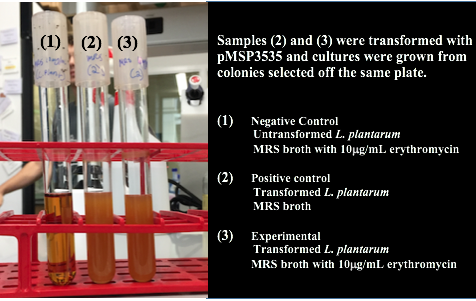

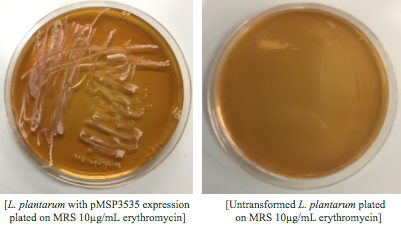

| − | <p style="font-family: verdana"><i> Lactobacillus plantarum </i> is a gram-positive lactic acid producing bacteria, so it requires a different growth media than we typically use in our lab. In 1954, Briggs agar was developed (9). This media was designed for <i>Lactobacilli</i>, but was not sufficient for many species, including <i> Lactobacillus plantarum </i>, so a different non-selective media for general <i>Lactobacilli</i> was developed in 1960 by Man, Rogosa and Sharpe and named MRS (10). We have exclusively grown our <i> Lactobacillus plantarum </i> on MRS media. Further, we grew <i> Lactobacillus plantarum </i> in a CO2 incubator as referenced in most literature we studied (11-13). The metabolic pathways in the bacteria alter when grown aerobically to produce excess acetate (14) and less lactic acid. Because we intend to utilize this bacteria in a fermentable food, a change in this metabolic pathway would not benefit our ultimate goal.</p> | + | <p style="font-family: verdana"><i> Lactobacillus plantarum </i> is a gram-positive lactic acid producing bacteria, so it requires a different growth media than we typically use in our lab. In 1954, Briggs agar was developed (9). This media was designed for <i>Lactobacilli</i>, but was not sufficient for many species, including <i> Lactobacillus plantarum </i>, so a different non-selective media for general <i>Lactobacilli</i> was developed in 1960 by Man, Rogosa and Sharpe and named MRS (10). We have exclusively grown our <i> Lactobacillus plantarum </i> on MRS media. Further, we grew <i> Lactobacillus plantarum </i> in a CO2 incubator as referenced in most literature we studied (11-13). The metabolic pathways in the bacteria alter when grown aerobically to produce excess acetate (14) and less lactic acid. Because we intend to utilize this bacteria in a fermentable food, a change in this metabolic pathway would not benefit our ultimate goal.<a href="https://2017.igem.org/Team:Austin_UTexas/Protocols">Click here for our MRS media recipe</a></p> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

| Line 318: | Line 305: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

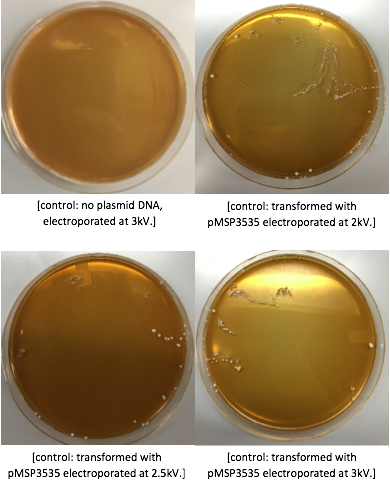

| − | <p style="font-family: verdana">The Texas Tech iGEM team helped us by testing the Speer protocol after we had attempted three procedures and hadn't successfully transformed. They were not able to successfully transform using the Speer protocol which suggests that the procedure was either too simplified for researchers who have never transformed gram-positive bacteria, or was not compatible with <i>Lactobacillus plantarum.</i> | + | <p style="font-family: verdana">The Texas Tech iGEM team helped us by testing the Speer protocol after we had attempted three procedures and hadn't successfully transformed. They were not able to successfully transform using the Speer protocol which suggests that the procedure was either too simplified for researchers who have never transformed gram-positive bacteria, or was not compatible with <i>Lactobacillus plantarum.</i><a href="https://2017.igem.org/Team:Austin_UTexas/Protocols">Click here for our electroporation protocol</a></p> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

Revision as of 16:13, 1 November 2017

Results

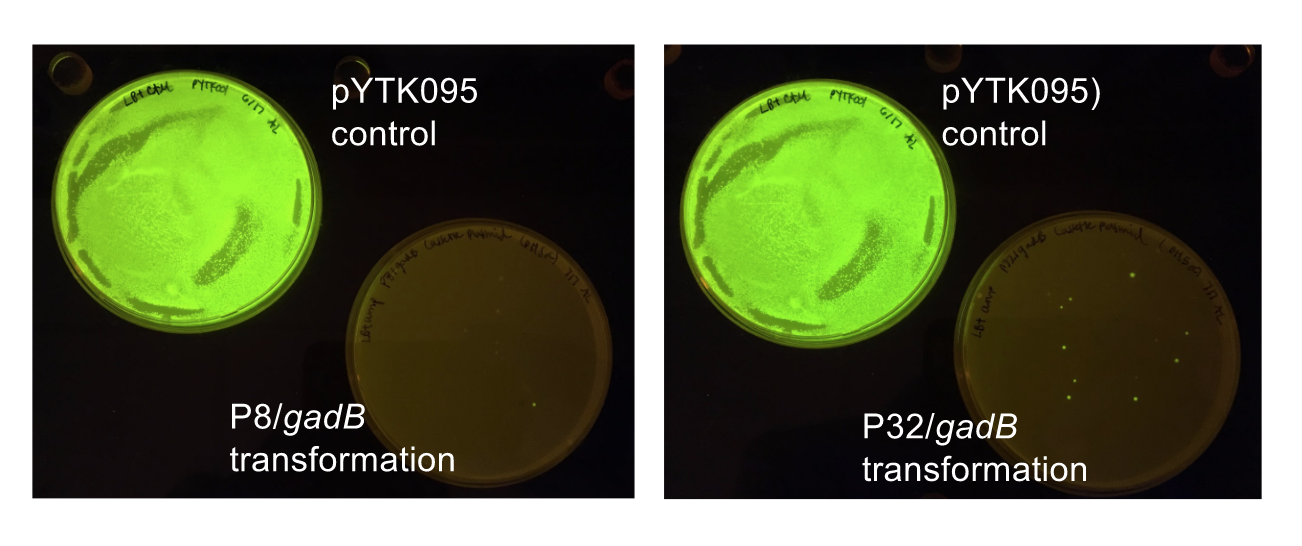

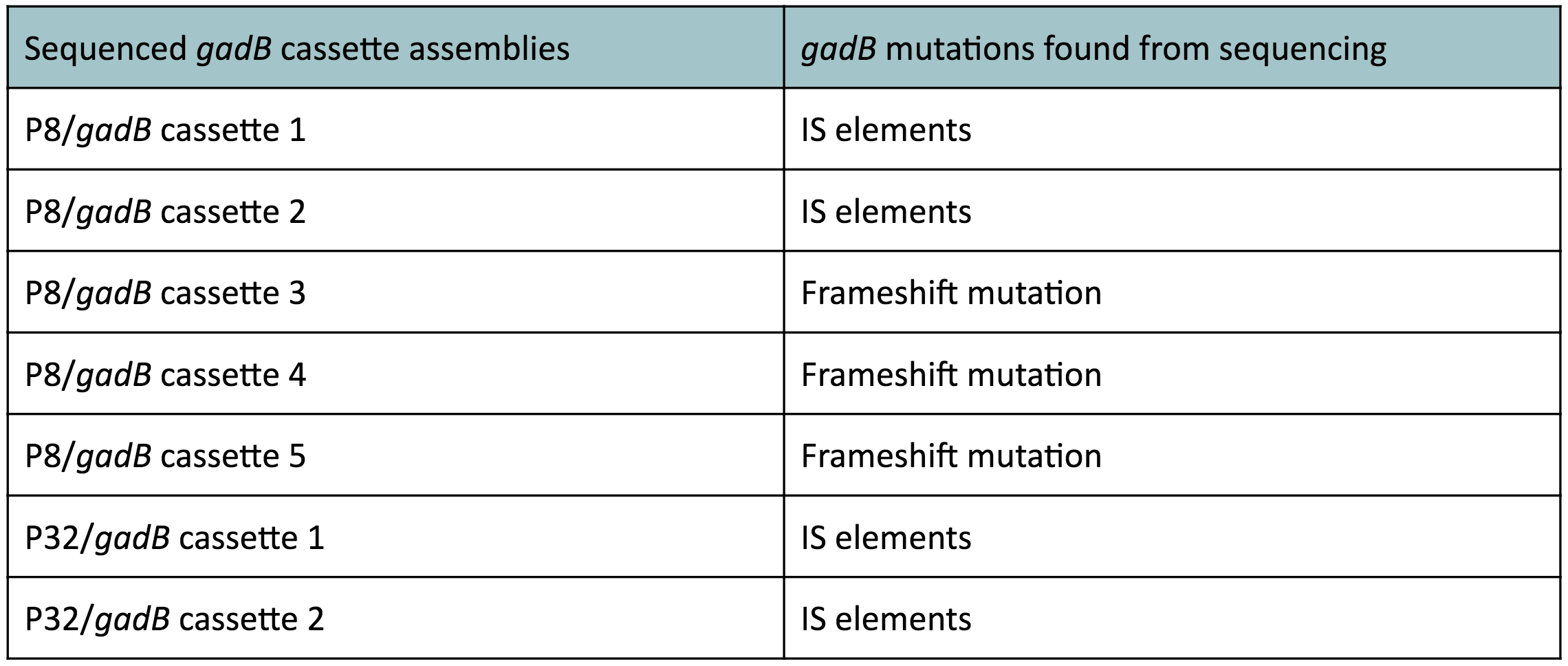

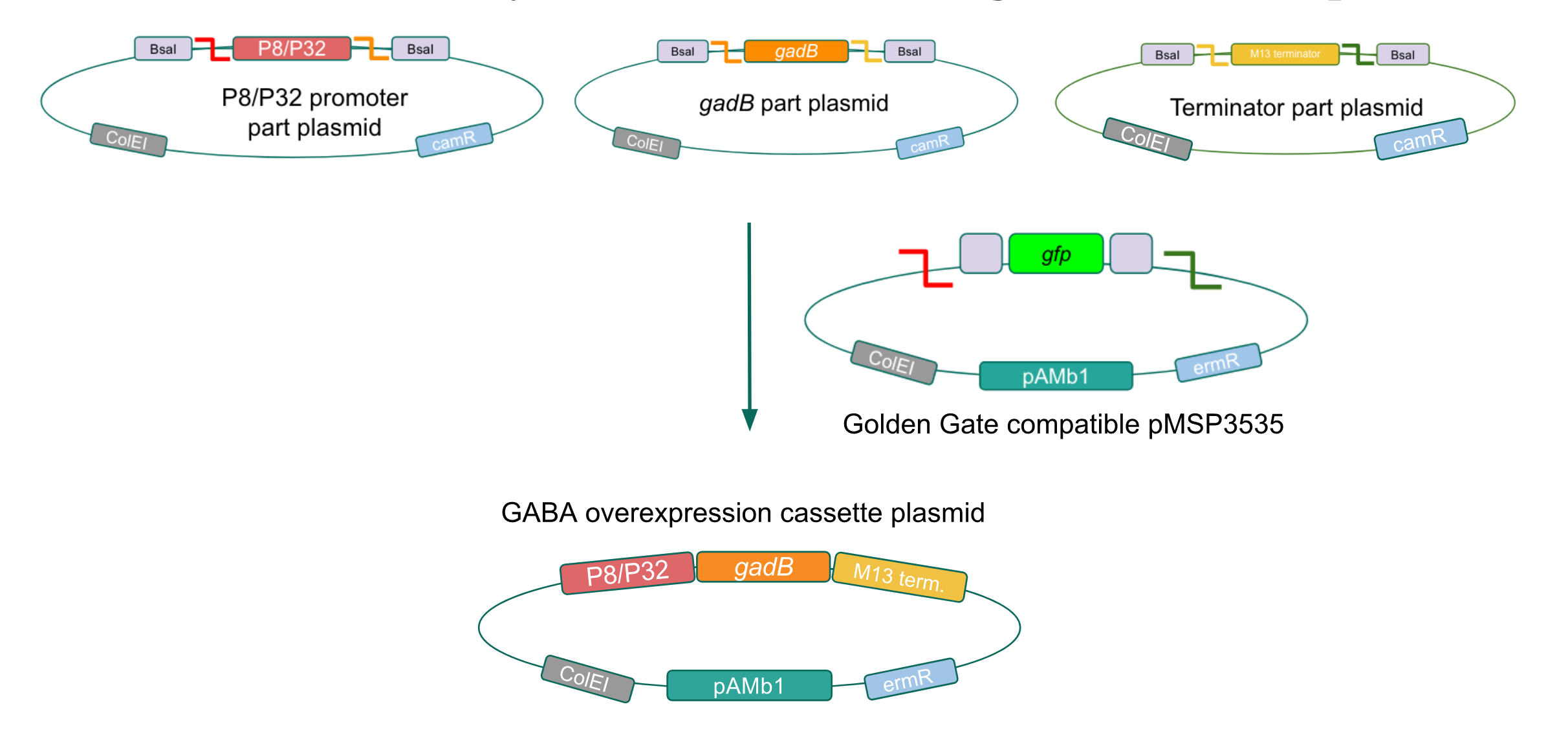

Although bacteria can naturally synthesize GABA, we wanted to increase expression of the gadB gene and subsequently GABA production in order to imbue our intended probiotic, Lactobacillus plantarum with a more potent medicinal quality, with the idea that this GABA-overproducing probiotic can then be consumed by patients with bowel disorders, hypternsion or anxiety (1). Overexpression of the gadB gene will be accomplished by placing it under the control of either the P8 or P32 constitutive promoters from Lactococcus lactis (2).

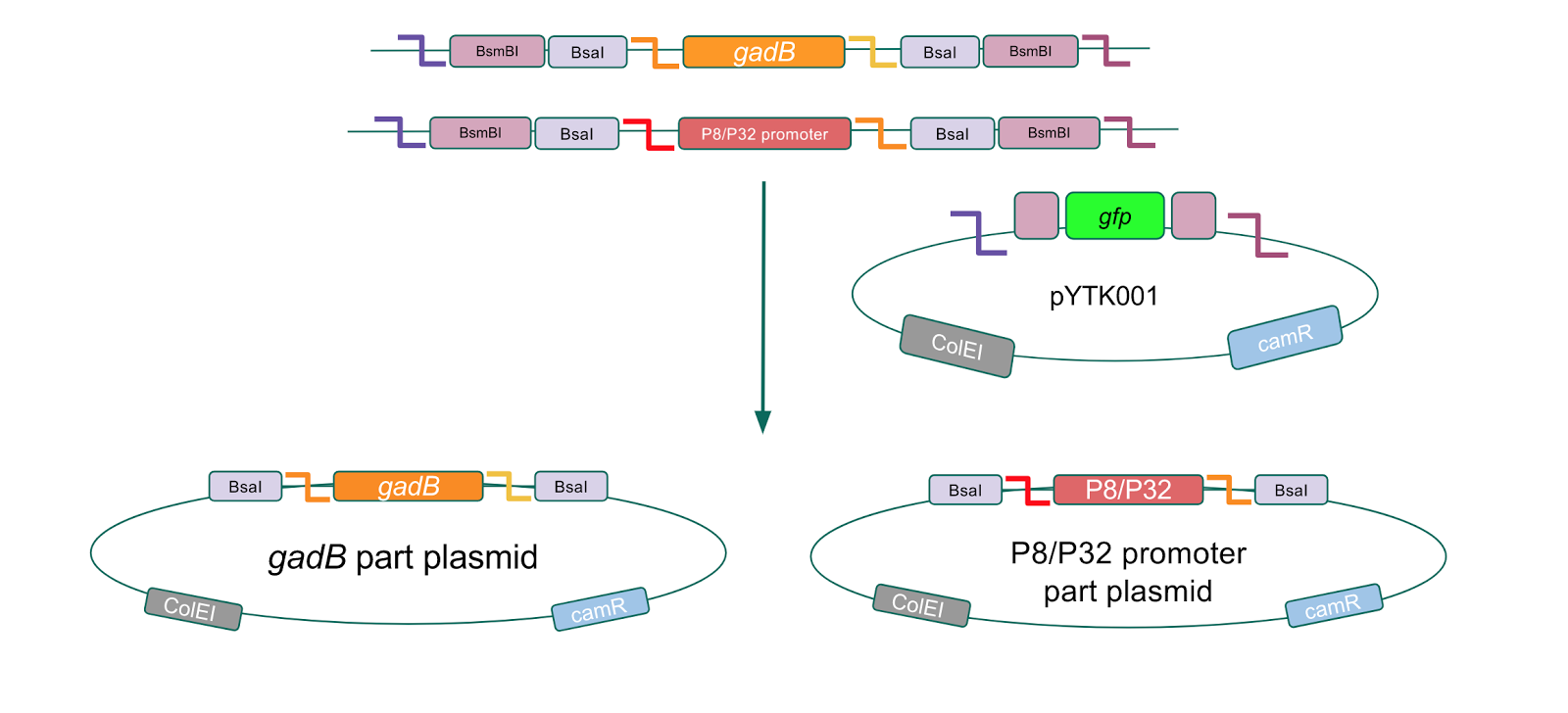

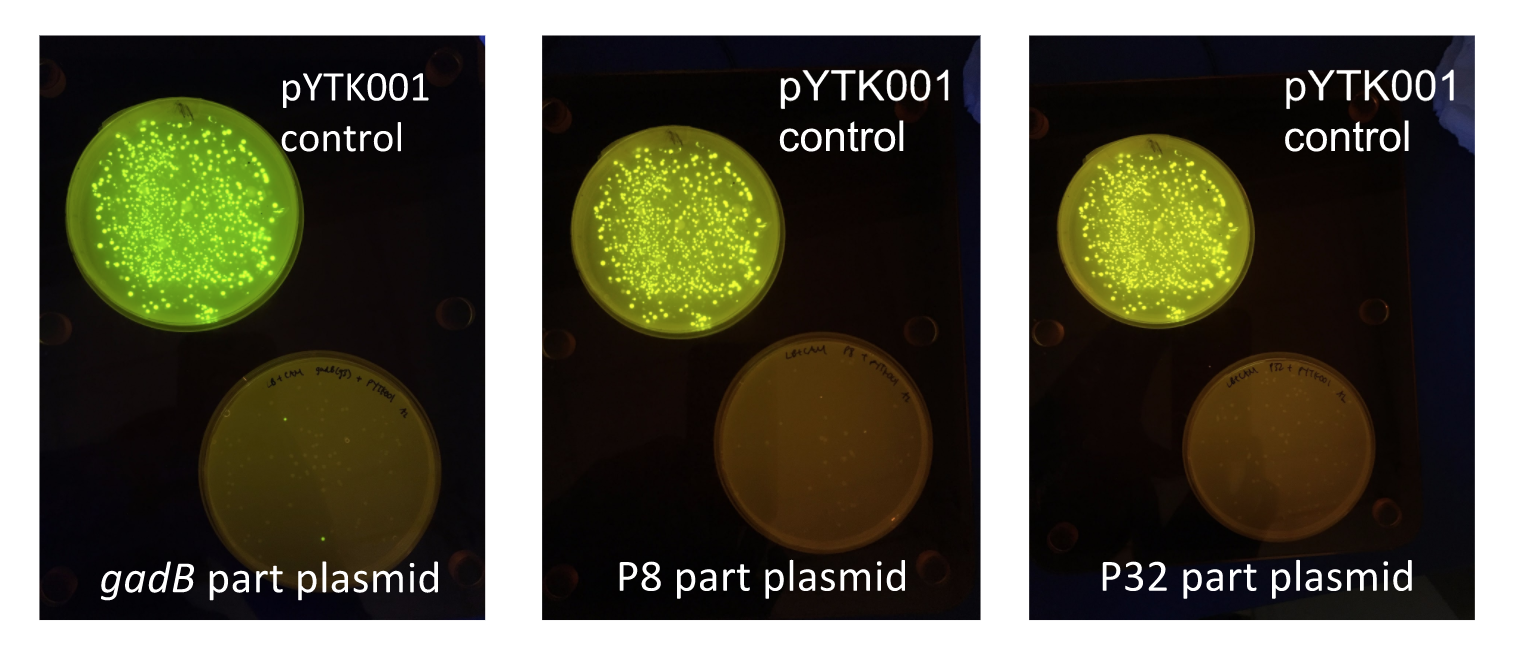

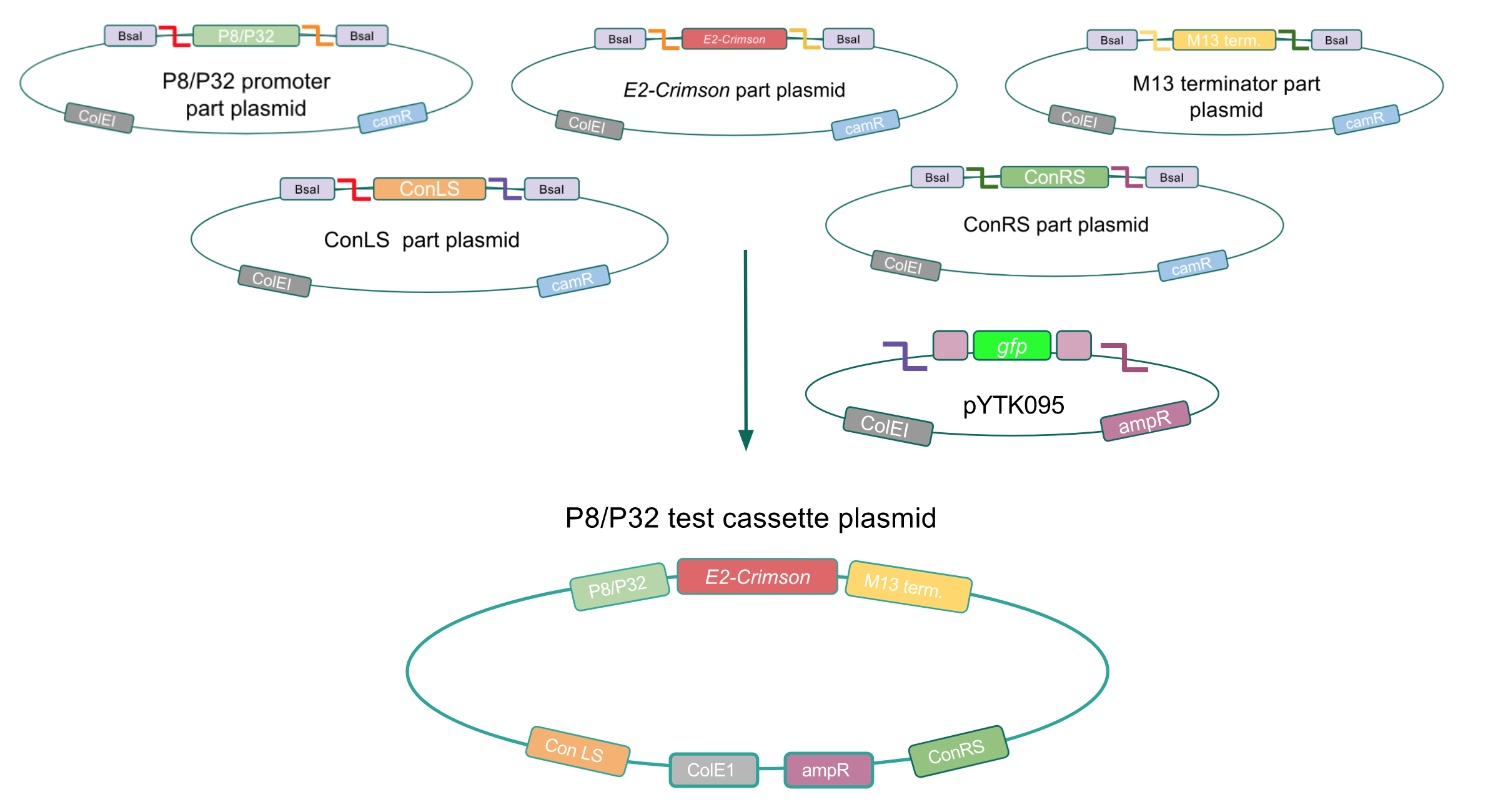

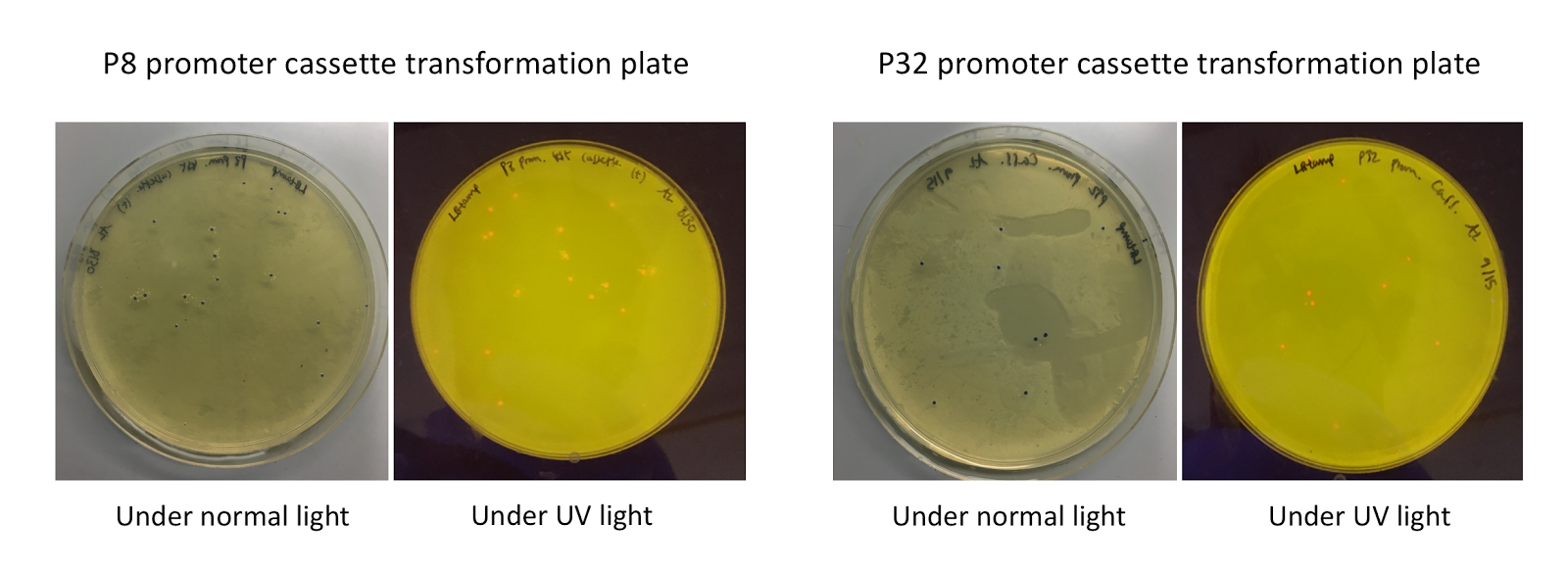

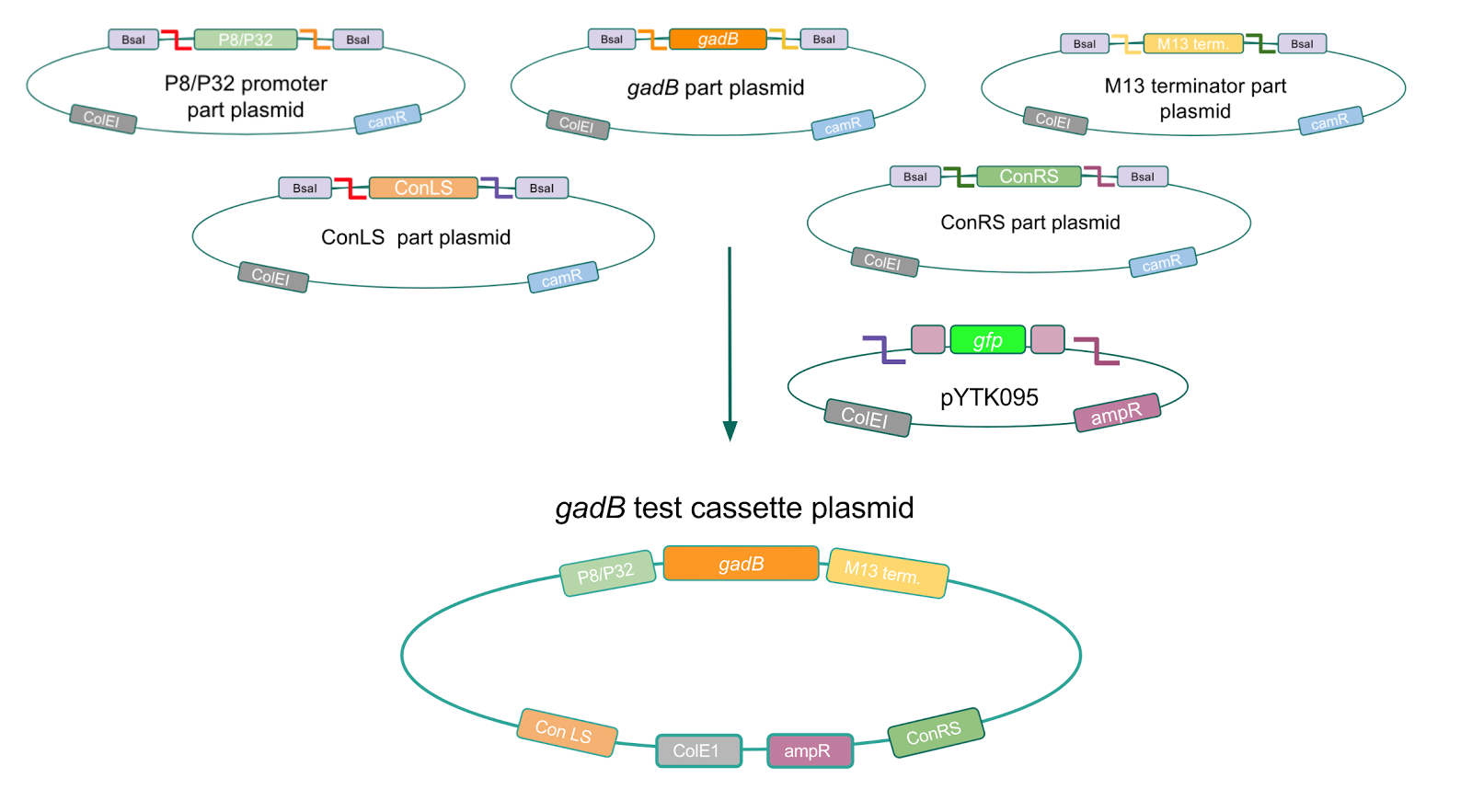

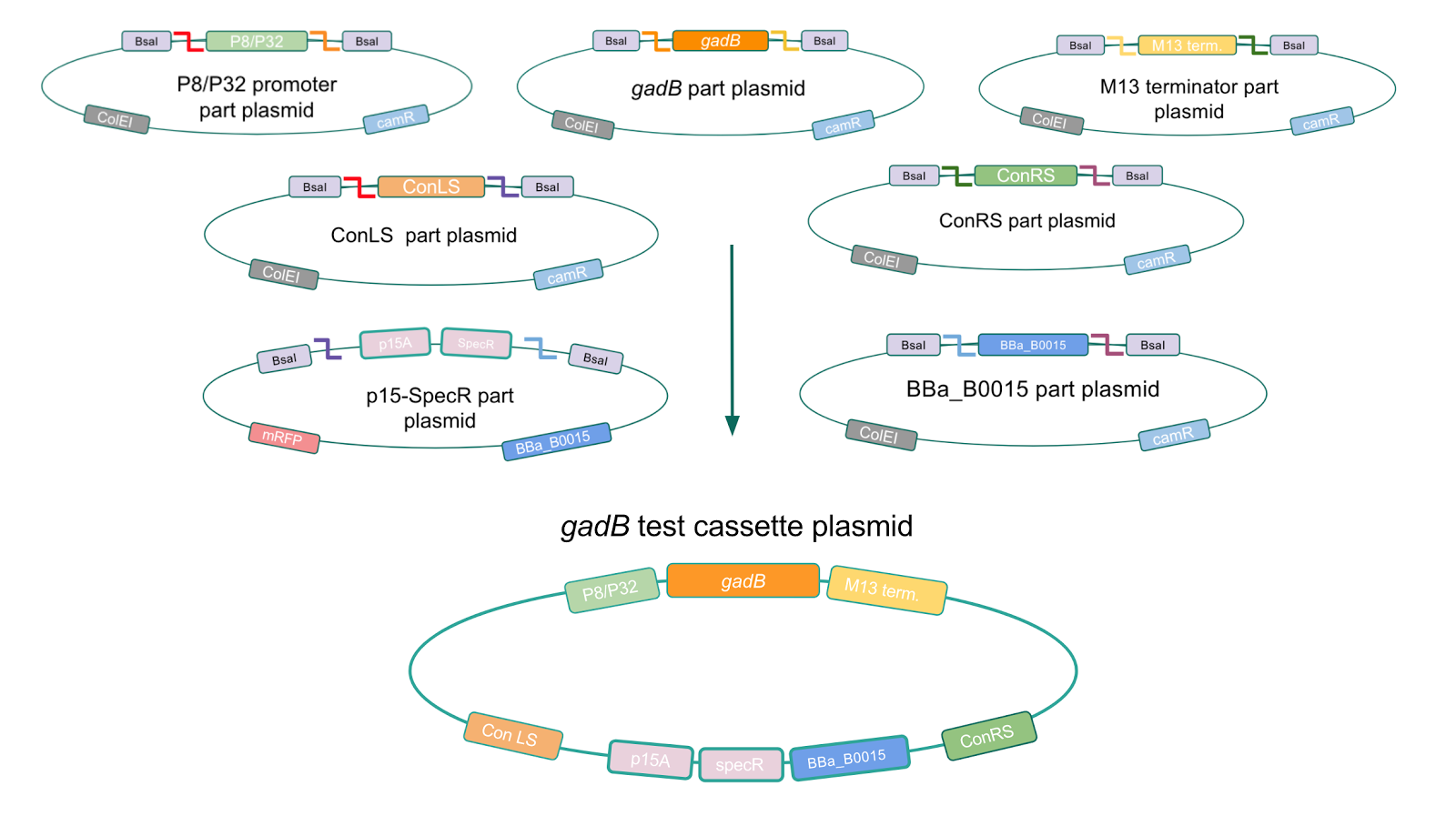

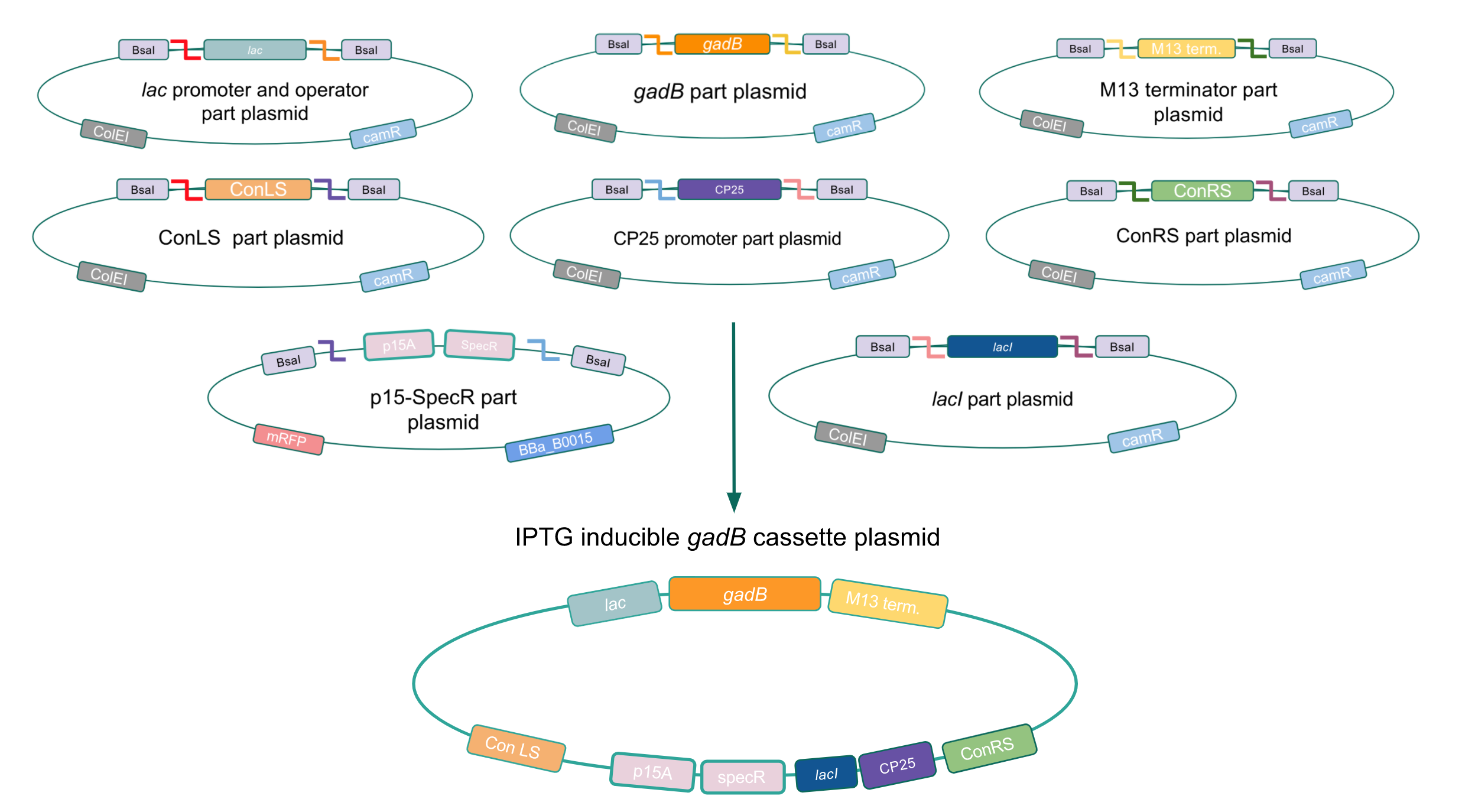

To make our GABA-producing probiotic, we ultimately needed to assemble a GABA overexpression cassette plasmid using the Golden Gate assembly method. The intention here is that bacteria containing this GABA overexpression cassette plasmid should produce high levels of GABA. In short, Golden Gate Assembly is a new cloning method that allows for the creation of a multi-part DNA assembly (i.e. cassette plasmid) in a single reaction through the use of DNA parts containing specific, predefined suffixes and prefixes with recognition sites for Type IIs restriction enzymes (e.g. BsmBI and BsaI). The specificity of these suffixes and prefixes provides directionality of the desired DNA parts during the assembly process. For our purposes, we used the MoClo Yeast Tool Kit developed by John Dueber (3).

We decided to first assemble and test our Golden Gate plasmids in E. coli, which was chosen due to the ease in which we could genetically manipulate it. We then wanted to use these Golden Gate plasmids to genetically manipulate L. platnarum. This part of the project required us to assemble a Golden Gate compatible shuttle vector (compatible in both E. coli and L. plantarum ) and transform L. plantarum. Our experimental results are detailed below.

Click on one of the images above to learn more about our results!

Golden Gate Compatible Shuttle Vector

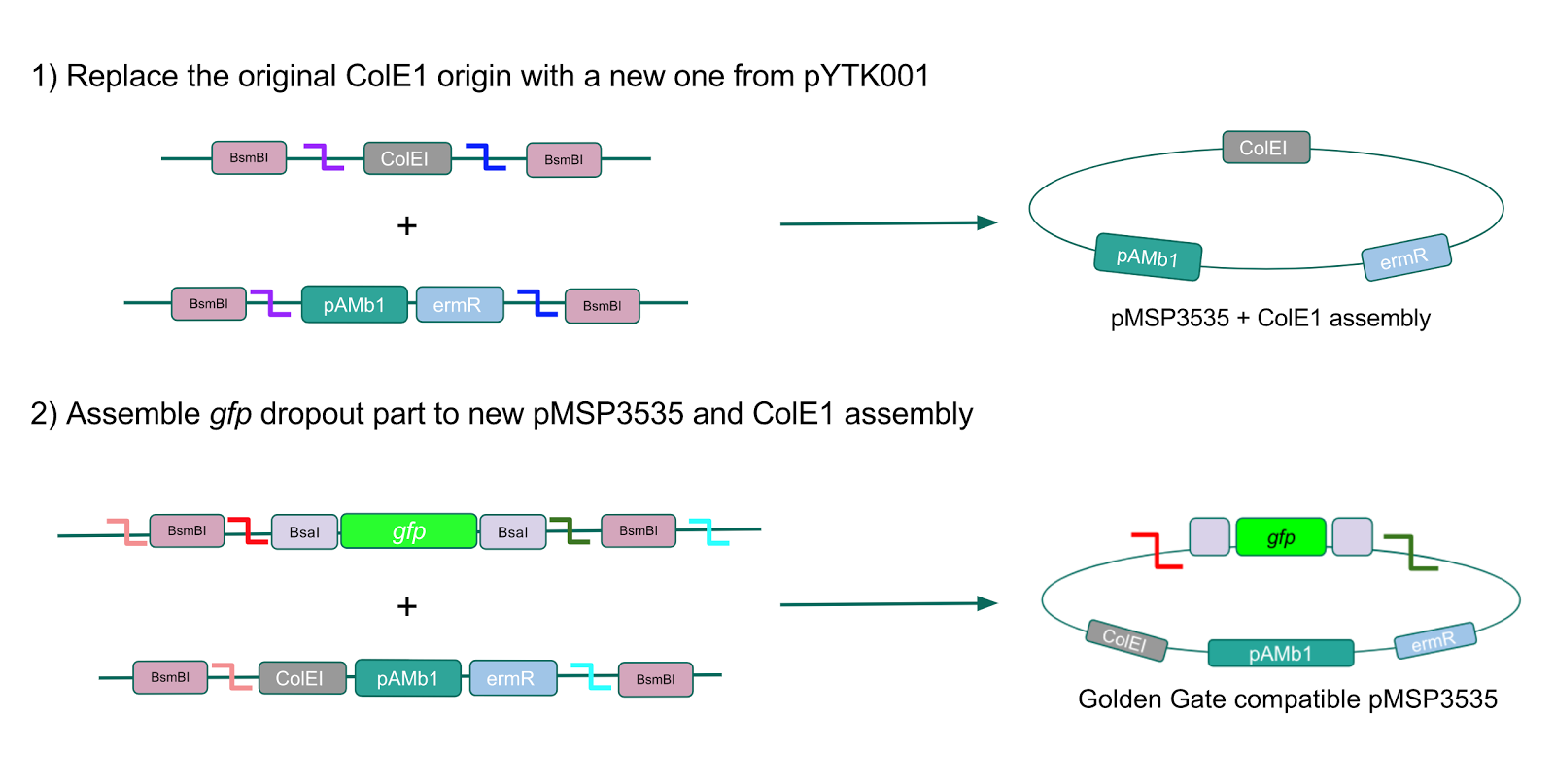

We wanted to assemble our final GABA overexpression cassette plasmid using the shuttle vector pMSP3535 as the backbone (Fig. 9). To do this, we first needed to make pMSP3535 Golden Gate compatible (i.e. free of BsaI restriction sites and containing correct overhangs for cassette assembly). We chose to work with pMSP3535 as it contains both a ColE1 origin for replication in E. coli and a pAMb1 origin for replication in Gram-positive bacteria including Lactobacillus species (7), allowing us to easily transplant our cassette plasmid from E. coli to Lactobacillus plantarum once assembled. Additionally, the pMSP3535 vector contains the resistance gene for erythromycin, of which Lactobacillus plantarum is naturally susceptible (8).

The process of making the pMSP3535 vector Golden Gate compatible involved two steps: 1) assembling the pMSP3535 backbone (pAMb1 origin and erythromycin resistance gene) with a new ColE1 origin; 2) assembling a gfp dropout part to the assembly of the pMSP3535 backbone and the new ColE1 origin (Fig. 10).

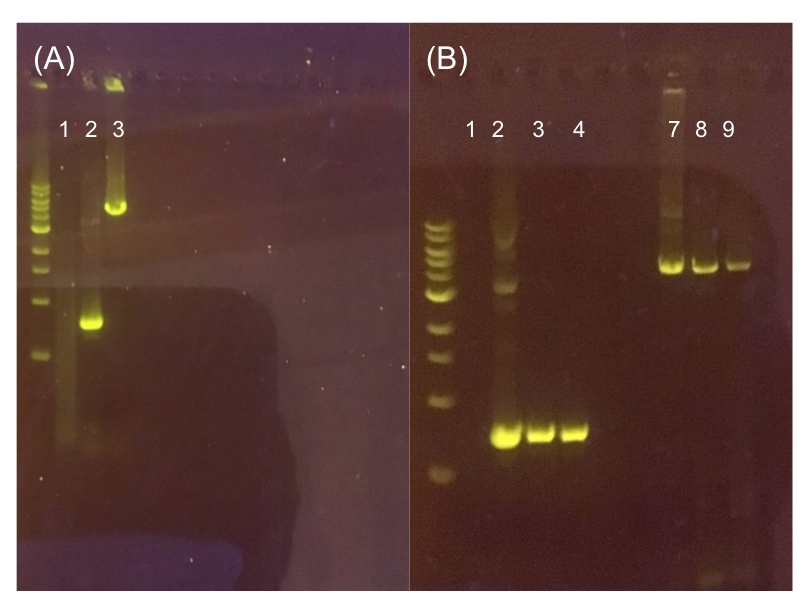

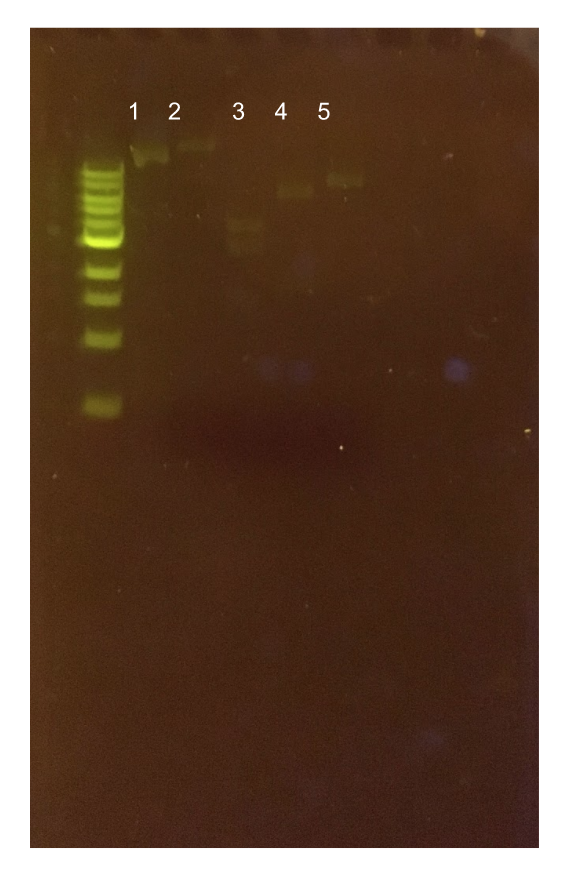

Since the original pMSP3535 vector contained two illegal BsaI sites within the ColE1 origin, we sought to replace this ColE1 origin with a BsaI-free one isolated from pYTK001. This assembly process involved linearizing and adding BsmBI sites and compatible overhangs to the pMSP3535 backbone and the pYTK001 ColE1 origin via PCR. After the pMSP3535 backbone and ColE1 origin were successfully amplified by PCR (Fig. 11a), they were joined together using BsmBI assembly. Diagnostic PCR was performed on pMSP3535 + ColE1 minipreps from E. coli transformants to screen for positive samples containing both the pMSP3535 backbone and the ColE1 inserts (Fig. 11b). After confirming the presence of the pMSP3535 vector and ColE1 origin, we partially sequence-confirmed the two miniprep samples.

To this pMSP3535 + ColE1 assembly, we wanted to add a gfp dropout part containing internal BsaI sites that will generate overhangs compatible with those in the P8/P32 promoter and M13 terminator part plasmids. Additionally, the incorporation of this gfp dropout part will also allow us to visually screen for positive and negative transformants based on their fluorescence. BsmBI sites and compatible overhangs were added to the gfp dropout part by PCR amplifying it from pYTK047. We have been attempting to linearize and add BsmBI sites and overhangs to the positive pMSP3535 + ColE1 assemblies via PCR, with no success. However, results from diagnostic digests suggested that our assemblies may have contained extra, undesired DNA such as IS elements (Fig. 12). Thus, as of right now, we are screening for more positive pMSP3535 + ColE1 transformants. Once we have trouble-shooted this problem, the pMSP3535 + ColE1 and the gfp dropout PCR products will be joined through BsmBI assembly to form the final Golden Gate compatible pMSP3535 vector.

Assessing erythromycin susceptibility of E. coli

Because we are creating our Golden Gate compatible pMSP3535 shuttle vector in E. coli, we wanted to determine the natural susceptibility of E. coli to erythromycin as the minimum concentration to use has not been established clearly in the literature. Thus, we performed an erythromycin minimum inhibitory concentration test in liquid LB media (Fig. 13). After one-day incubation, we observed that E. coli was resistant up to around 150 µg/mL of erythromycin. From this experiment, we have determined that the optimal erythromycin concentration for selecting against E. coli in liquid culture is around 200-250 µg/mL.