| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

<p> One of the main goals of our project was to genetically engineer <i>Lactobacillus plantarum</i> to produce high amounts of GABA through overexpression of the <i>gadB</i> gene. In order to do this, we first had to be able to transform <i>L. plantarum</i> via electroporation. We used the pMSP3535 vector for transformation as it contains the erythromycin resistance gene and a pAMb1 origin that is compatible in Gram-positive bacteria, including <i>Lactobacillus</i>. The pMSP3535 vector contains a ColE1 origin for replication in <i>E. coli</i>. Due to having both the ColE1 and pAMb1 origins, the pMSP3535 was intended to be used as a shuttle vector for creating and testing our GABA overexpression cassette first in <i>E. coli</i>. The functional GABA overexpression cassette would then be transformed into <i>L. plantarum</i> using electroporation. Thus, transforming <i>L. plantarum</i> with the pMSP3535 shuttle vector was central to our project. | <p> One of the main goals of our project was to genetically engineer <i>Lactobacillus plantarum</i> to produce high amounts of GABA through overexpression of the <i>gadB</i> gene. In order to do this, we first had to be able to transform <i>L. plantarum</i> via electroporation. We used the pMSP3535 vector for transformation as it contains the erythromycin resistance gene and a pAMb1 origin that is compatible in Gram-positive bacteria, including <i>Lactobacillus</i>. The pMSP3535 vector contains a ColE1 origin for replication in <i>E. coli</i>. Due to having both the ColE1 and pAMb1 origins, the pMSP3535 was intended to be used as a shuttle vector for creating and testing our GABA overexpression cassette first in <i>E. coli</i>. The functional GABA overexpression cassette would then be transformed into <i>L. plantarum</i> using electroporation. Thus, transforming <i>L. plantarum</i> with the pMSP3535 shuttle vector was central to our project. | ||

| − | After using various electrotransformation protocols, we were able to successfully transform <i>L. plantarum</i> with the pMSP3535 vector. As can be seen in <b>Figure 1</b>, the <i>L. plantarum</i> transformants grew on selective plates containing erythromycin. In comparison, the untransformed <i>L. plantarum</i> control did not grow on the erythromycin plate.</i>From this transformation experiment, we have demonstrated that we were able to successfully transform our <i>L. plantarum</i> probiotic. In doing so, we have also demonstrated that the compatability of the pMSP3535 vector in <i>L. | + | After using various electrotransformation protocols, we were able to successfully transform <i>L. plantarum</i> with the pMSP3535 vector. As can be seen in <b>Figure 1</b>, the <i>L. plantarum</i> transformants grew on selective plates containing erythromycin. In comparison, the untransformed <i>L. plantarum</i> control did not grow on the erythromycin plate.</i>From this transformation experiment, we have demonstrated that we were able to successfully transform our <i>L. plantarum</i> probiotic. In doing so, we have also demonstrated that the compatability of the pMSP3535 vector in <i>L. plantarum</i> |

Revision as of 00:32, 2 November 2017

Demonstrate

gadB overexpression

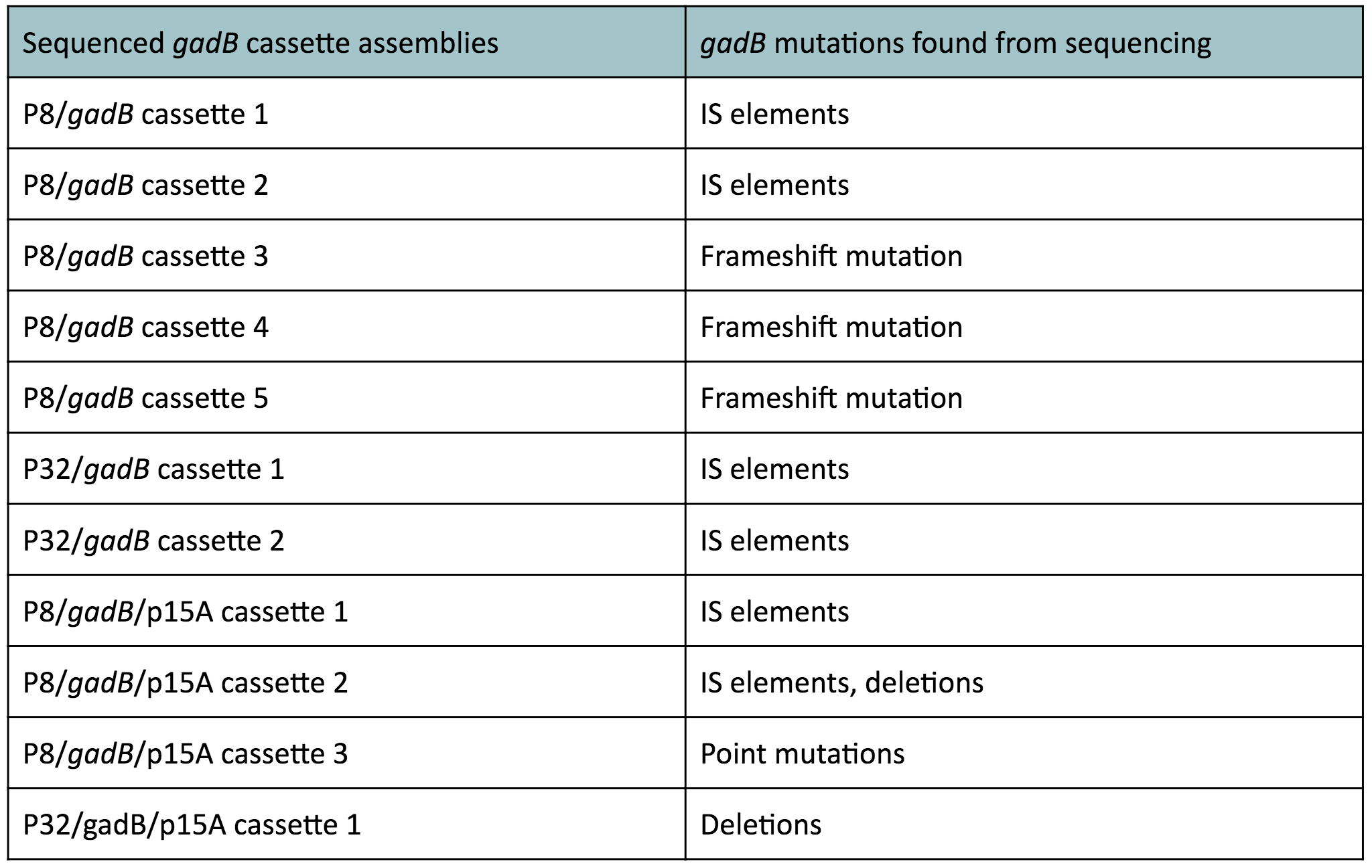

In summary, we generated two sets of cassette plasmids to increase gadB expression through the use of constitutive promoters. The first set of cassette plasmids contained the high-copy number ColE1 origin and the other set contained the low-copy number p15A origin. The gadB part plasmid used in these assemblies was sequence-verified. Nonetheless, from these experiments, it was evident that constitutive expression of the gadB gene led to its mutational inactivation.

It is most likely that our cassette transformants were able to overexpress the gadB gene. However, gadB overexpression was metabolically-taxing to these cells, as the glutamate typically used for important cellular growth processes was being allocated towards GABA production, which was a process that did not confer a selective advantage. As a result, subsequent generations of these cells initially overexpressing gadB began to "break" the gadB gene. After several generations, the colonies that appeared on our plates represented only the clones containing the mutationally inactivated gadB gene. These cells were selectively favored in the population, as having a broken gadB gene allowed them to utilize glutamate sources for growth processes, providing a competitive advantage over other cells containing the functional, metabolically-burdensome gadB gene. Observed mutations of the gadB gene in our cassette assemblies, which can be seen in Table 1 below, indirectly demonstrates its intial overepxression in the original population of transformants followed by its mutational inactivation in subsequent surviving generations.

Lactobacillus plantarum transformation

One of the main goals of our project was to genetically engineer Lactobacillus plantarum to produce high amounts of GABA through overexpression of the gadB gene. In order to do this, we first had to be able to transform L. plantarum via electroporation. We used the pMSP3535 vector for transformation as it contains the erythromycin resistance gene and a pAMb1 origin that is compatible in Gram-positive bacteria, including Lactobacillus. The pMSP3535 vector contains a ColE1 origin for replication in E. coli. Due to having both the ColE1 and pAMb1 origins, the pMSP3535 was intended to be used as a shuttle vector for creating and testing our GABA overexpression cassette first in E. coli. The functional GABA overexpression cassette would then be transformed into L. plantarum using electroporation. Thus, transforming L. plantarum with the pMSP3535 shuttle vector was central to our project. After using various electrotransformation protocols, we were able to successfully transform L. plantarum with the pMSP3535 vector. As can be seen in Figure 1, the L. plantarum transformants grew on selective plates containing erythromycin. In comparison, the untransformed L. plantarum control did not grow on the erythromycin plate.From this transformation experiment, we have demonstrated that we were able to successfully transform our L. plantarum probiotic. In doing so, we have also demonstrated that the compatability of the pMSP3535 vector in L. plantarum