Although bacteria can naturally synthesize GABA, we wanted to increase expression of the gadB gene and subsequently GABA production in order to imbue our probiotic with a more potent medicinal quality, with the idea that this GABA-overproducing probiotic can then be consumed by patients with bowel disorders or anxiety (1). Overexpression of the gadB gene will be accomplished by placing it under the control of either the P8 or P32 constitutive promoters from Lactococcus lactis (2).

To make our GABA-producing probiotic we first needed to assemble a GABA overexpression cassette plasmid using the Golden Gate assembly method. The intention here is that bacteria containing this GABA overexpression cassette plasmid should produce high levels of GABA. In short, Golden Gate Assembly is a new cloning method that allows for the creation of a multi-part DNA assembly (i.e. cassette plasmid) in a single reaction through the use of DNA parts containing specific, predefined suffixes and prefixes with recognition sites for Type IIs restriction enzymes (e.g. BsmBI and BsaI). The specificity of these suffixes and prefixes provides directionality of the desired DNA parts during the assembly process. For our purposes, we used the MoClo Yeast Tool Kit developed by John Dueber (3).

Part Assembly

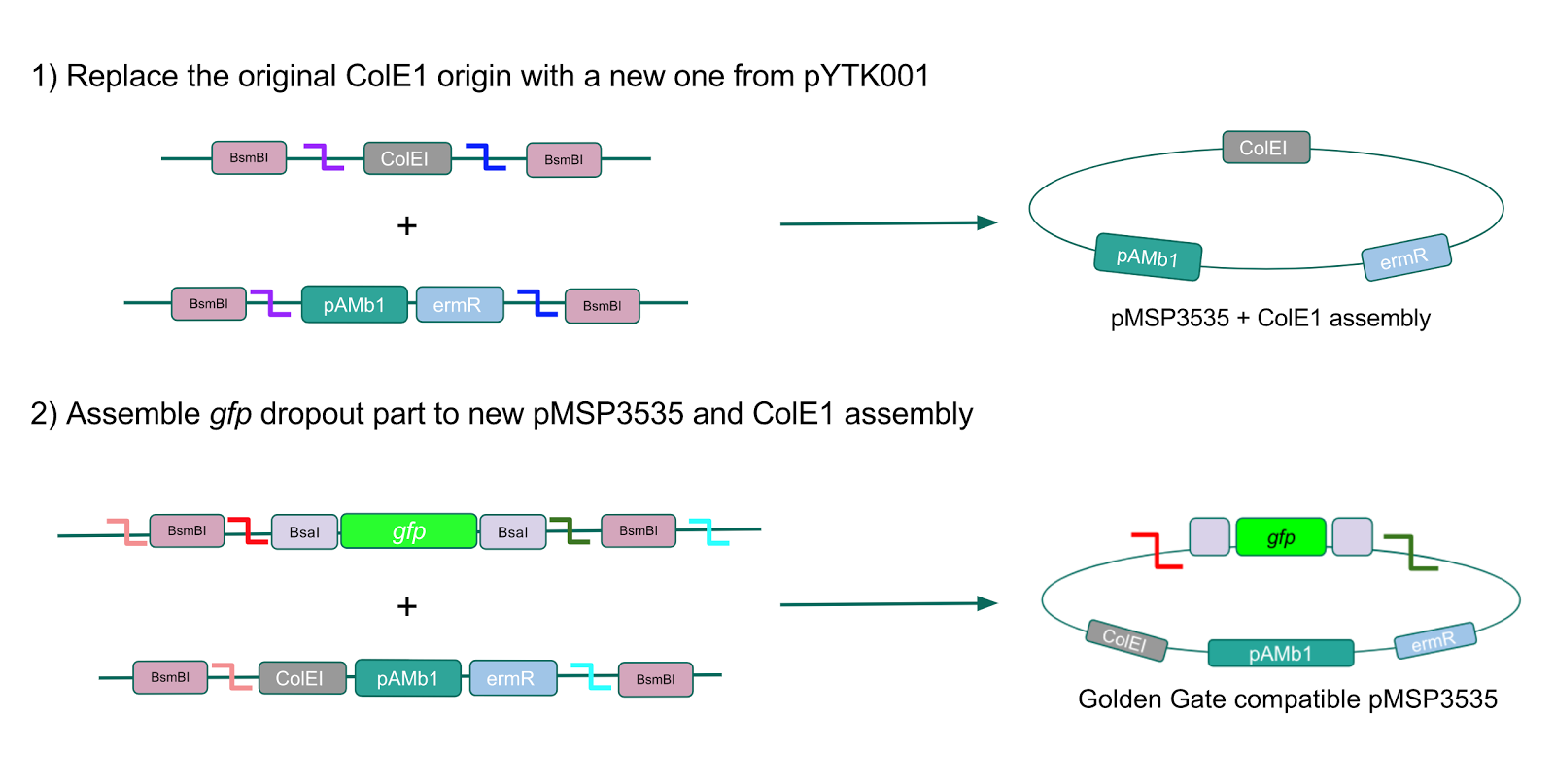

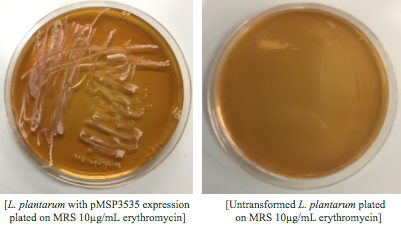

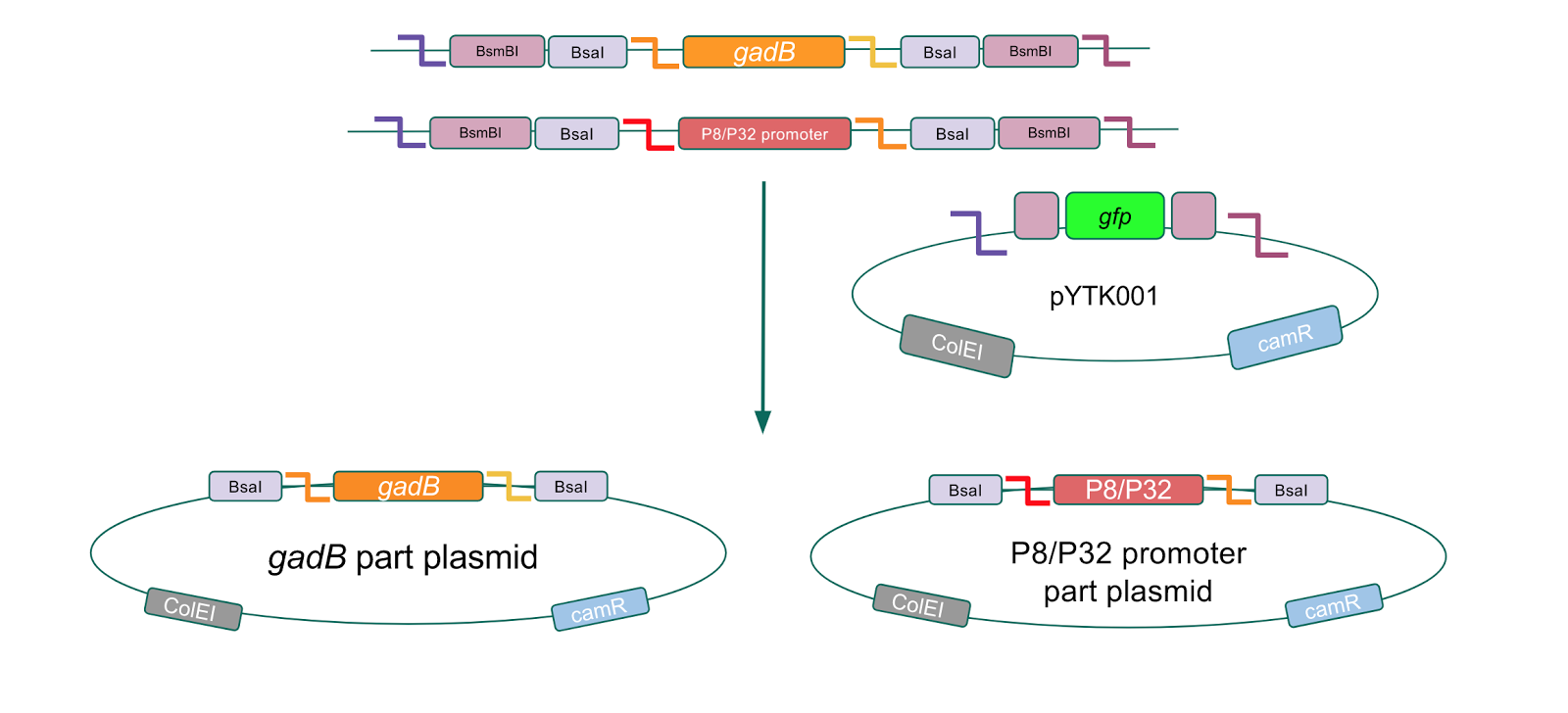

The first part of our Golden Gate assembly workflow was part assembly, in which the gadB gene and the P8/P32 promoters were individually cloned into the entry vector pYTK001 (Fig. 1). The gadB gene and P8/P32 promoter sequences contain flanking BsmBI sites that produce overhangs compatible with those cut by BsmBI in the entry vector pYTK001. Thus, BsmBI cloning should result in part plasmids containing the gadB gene and P8/P32 promoters set within the pYTK001 backbone.

Figure 1. gadB gene and P8/P32 promoter part assembly process. Golden Gate compatible

gadB and P8/P32 promoter sequences are cloned into the pYTK001 entry vector via BsmBI assembly.

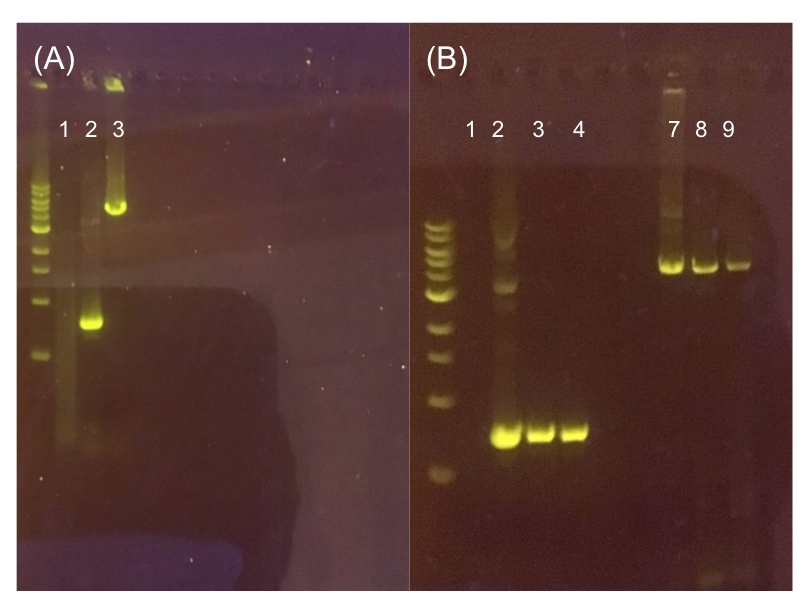

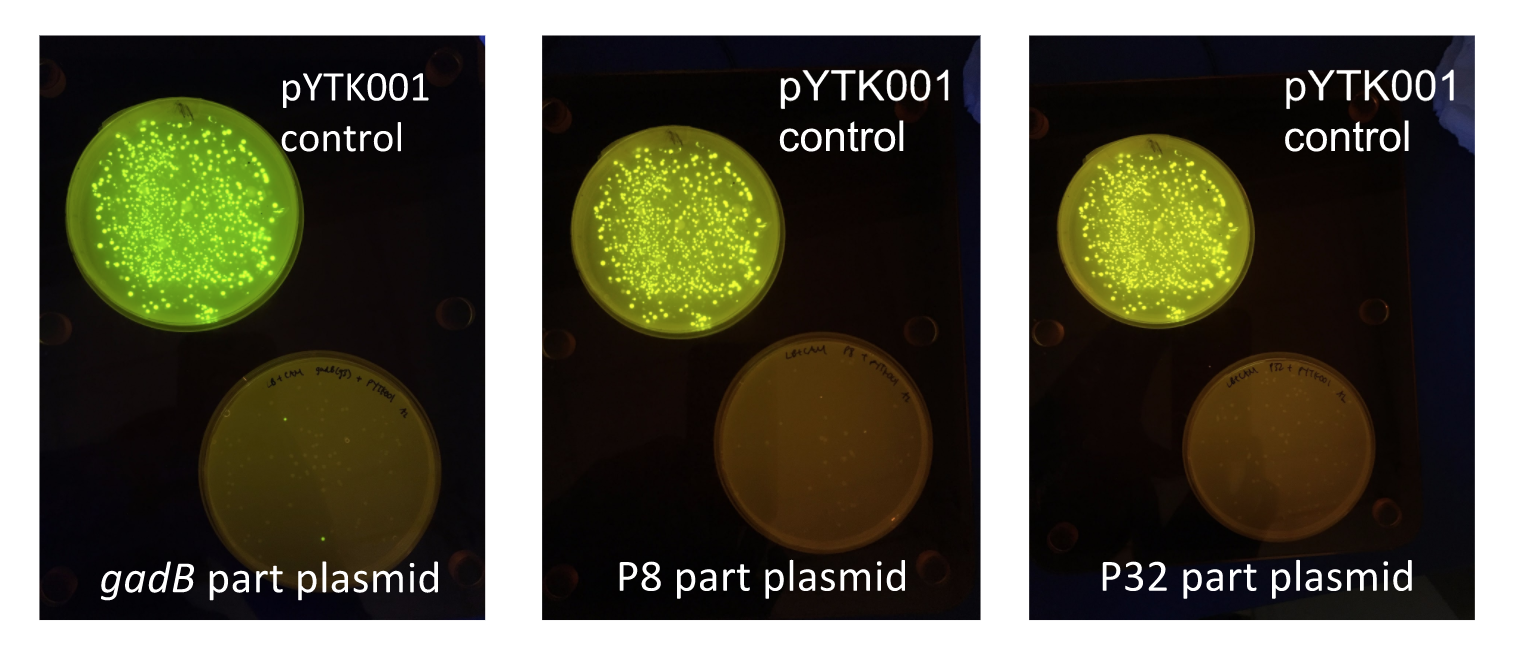

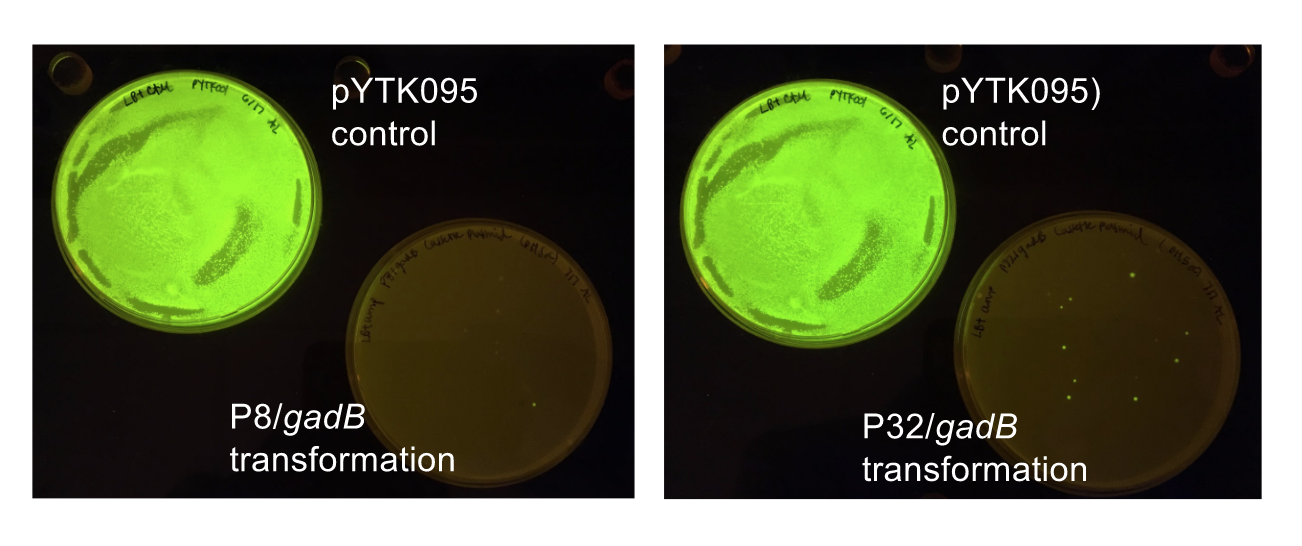

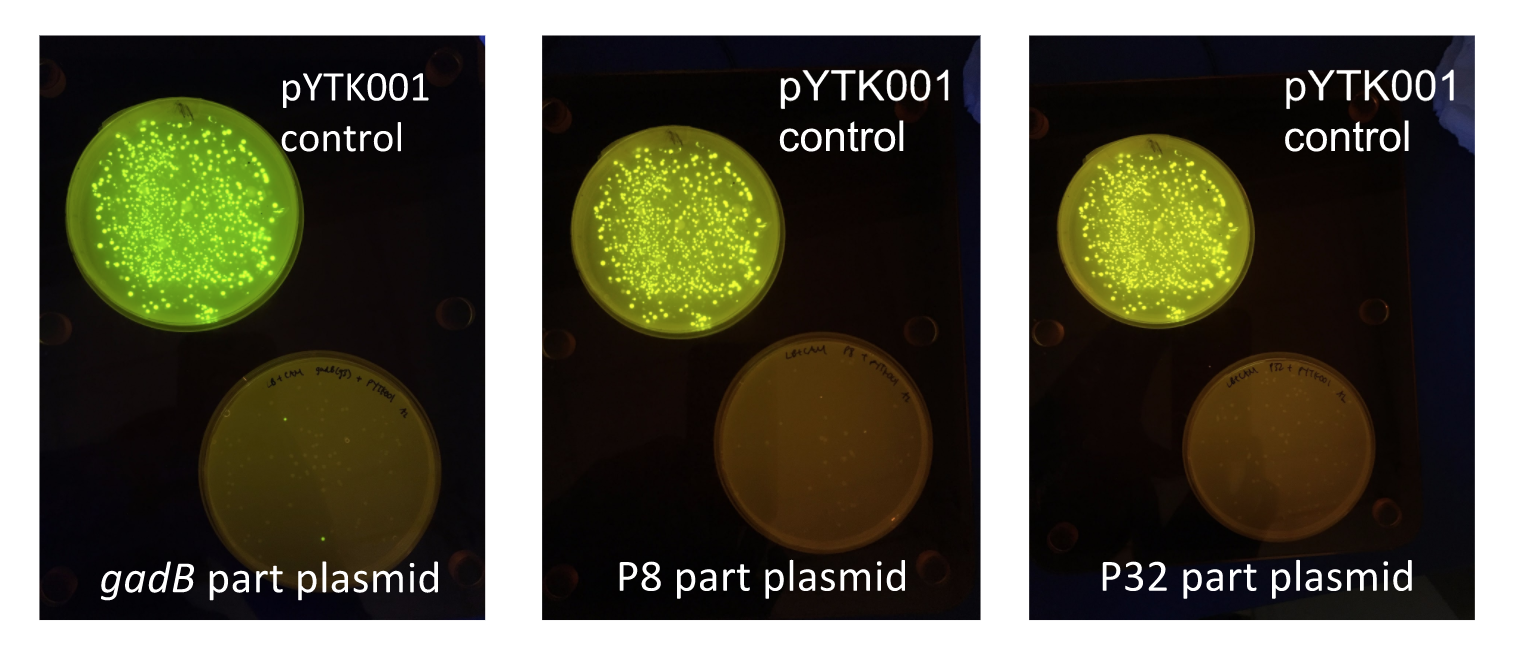

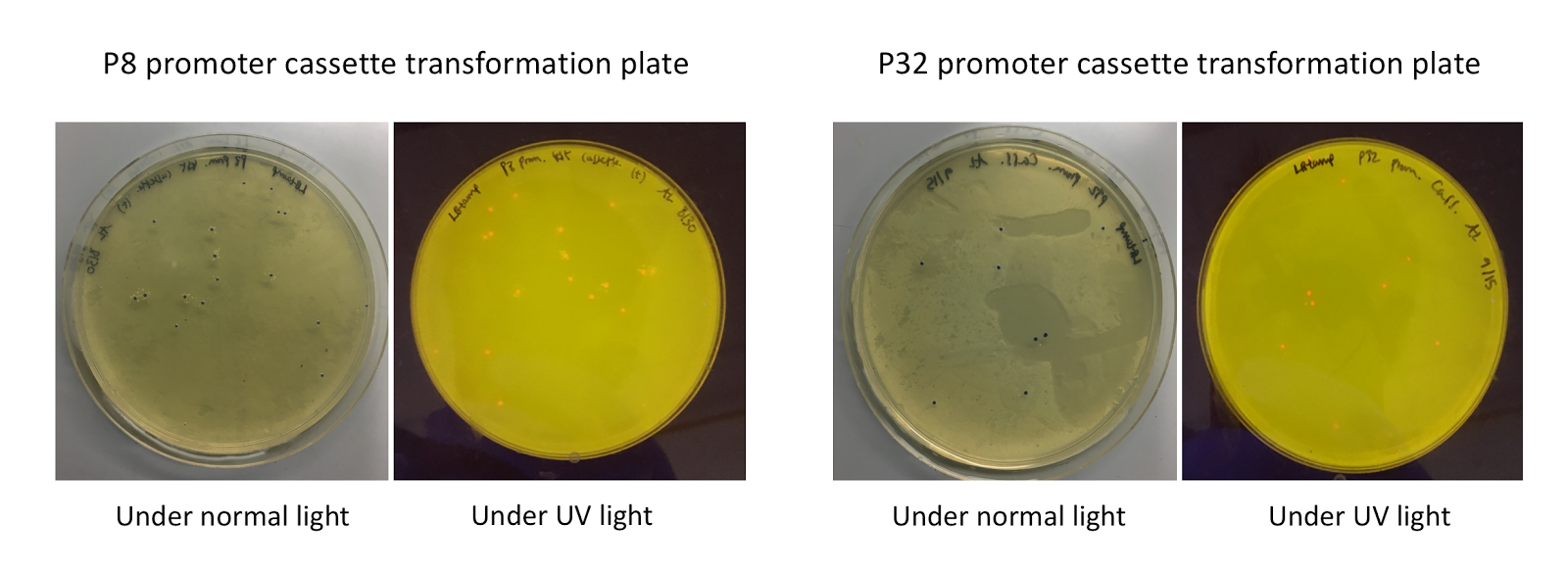

Additionally, the BsmBI sites and overhangs in pYTK001 are flanking a gfp reporter gene. During the part assembly process, our DNA sequences of interest replaced this gfp reporter gene. This provided a phenotypic screen that allowed us to visually see which transformant colonies were negative and potentially positive. Under UV illumination, positive colonies containing our intended part plasmid assembly did not exhibit fluorescence under the UV illumination, while negative colonies did (Fig. 2). The non-fluorescent colonies on the part plasmid transformation plates were miniprepped and subsequently sequence verified.

Figure 2. gadB gene and P8/P32 promoter part plasmid

E. coli transformations, compared to control transformations with pYTK001. Under UV illumination, transformants containing the correctly assembled part plasmids were non-fluorescent while negative transformants appeared fluorescent like colonies on the control plates.

Back to Top

Testing constitutive Lactococcal promoters

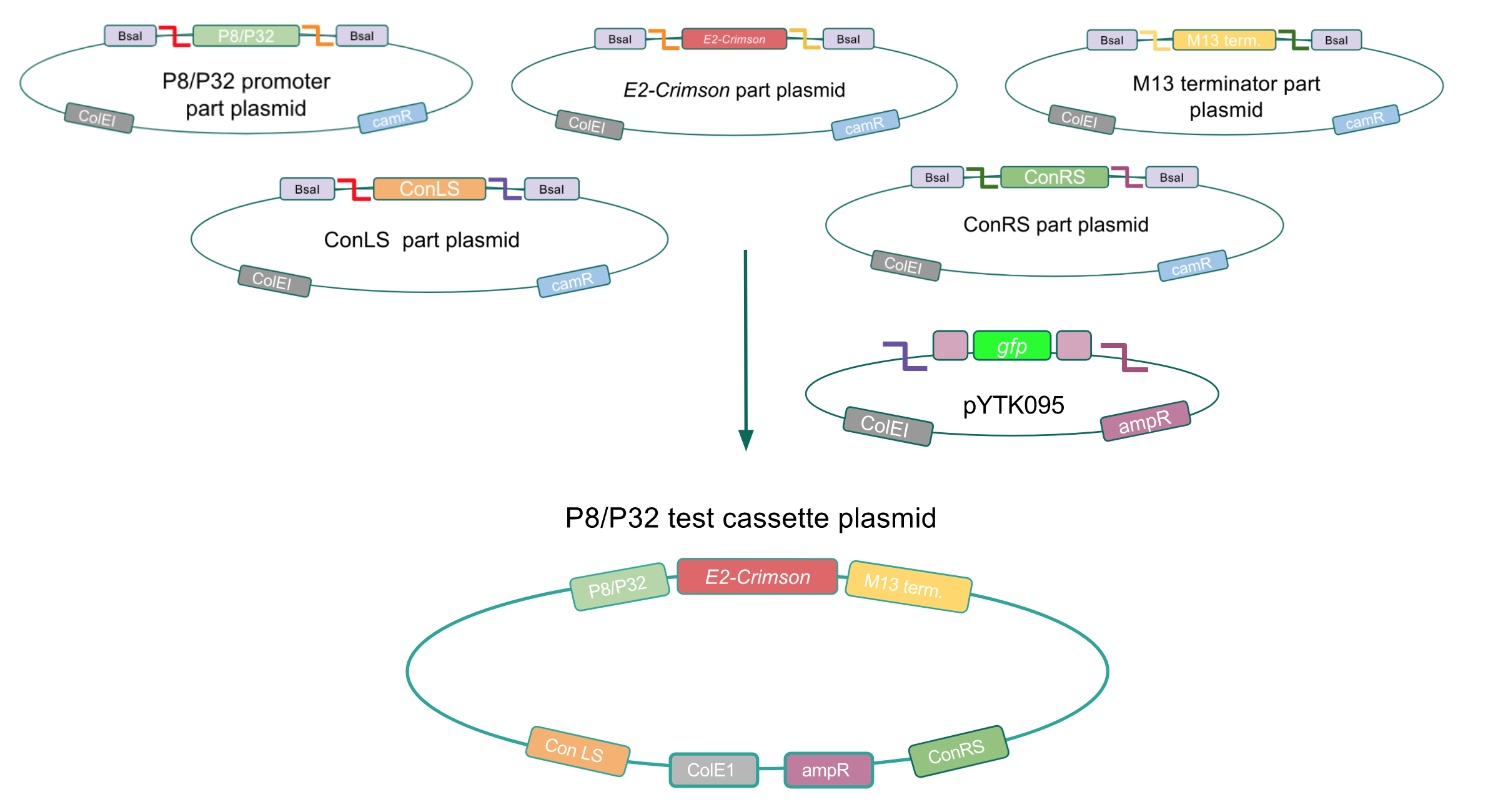

After successfully creating the gadB gene and P8/P32 promoter part plasmids, the functionality of these part plasmids were then assessed by assembling them into cassette plasmids.

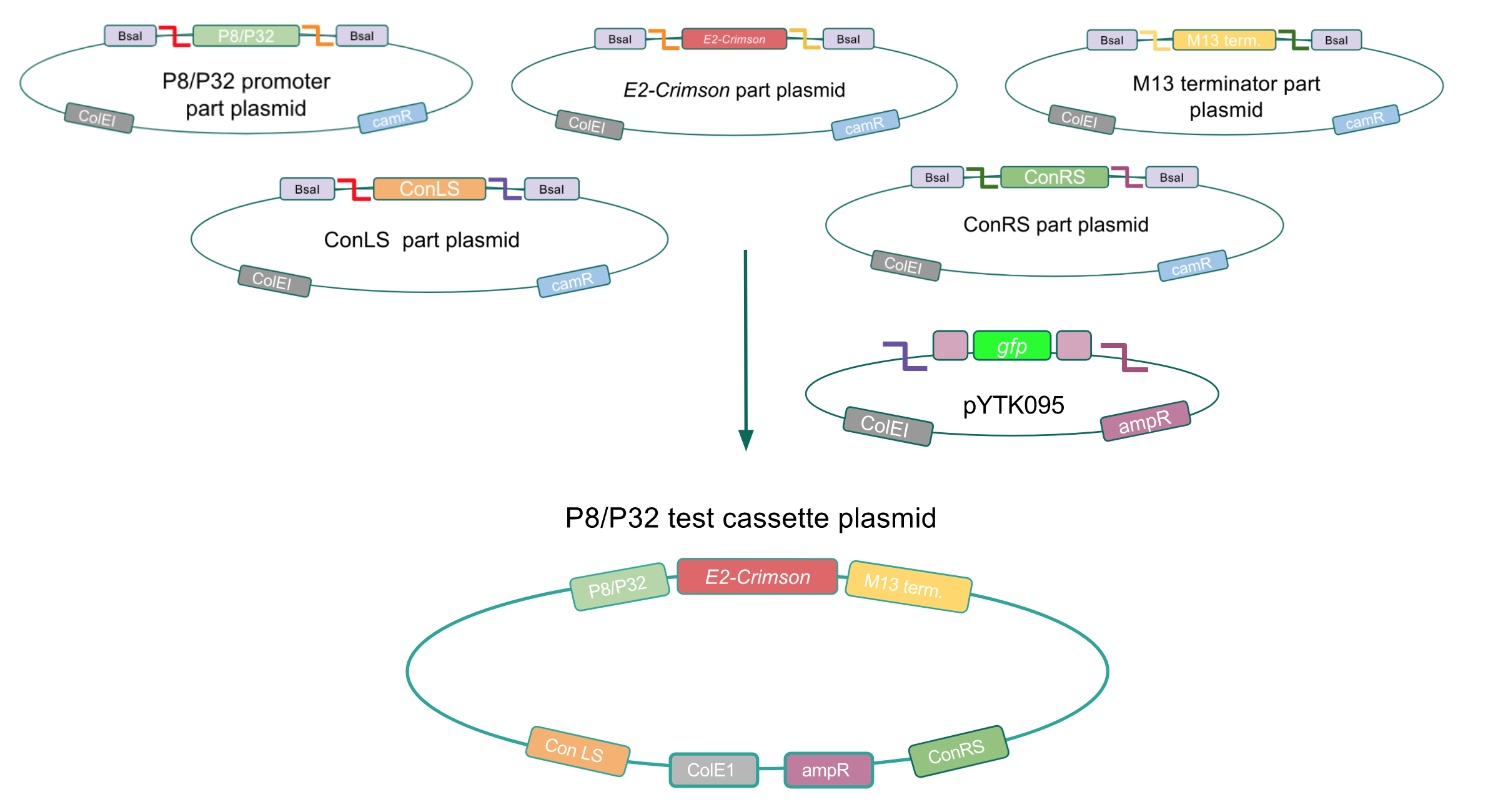

To test if our Lactococcus lactis constitutive promoters function well within E. coli, we created test cassette plasmids containing the E2-Crimson reporter gene (which encodes a red fluorescent protein) inserted downstream of either the P8 or P32 promoters using BsaI Golden Gate assembly. To create these test cassettes, we used the P8/P32 promoter part plasmids, the E2-Crimson part plasmid, an M13 terminator part plasmid, connector part plasmids, and the pYTK095 vector as the backbone (Fig. 3). If the P8 and P32 promoters are functional in E. coli, we expected to observe red fluorescence in colonies transformed with our test cassette plasmids.

Figure 3. Golden Gate assembly process of the P8 and P32 test cassette plasmids.

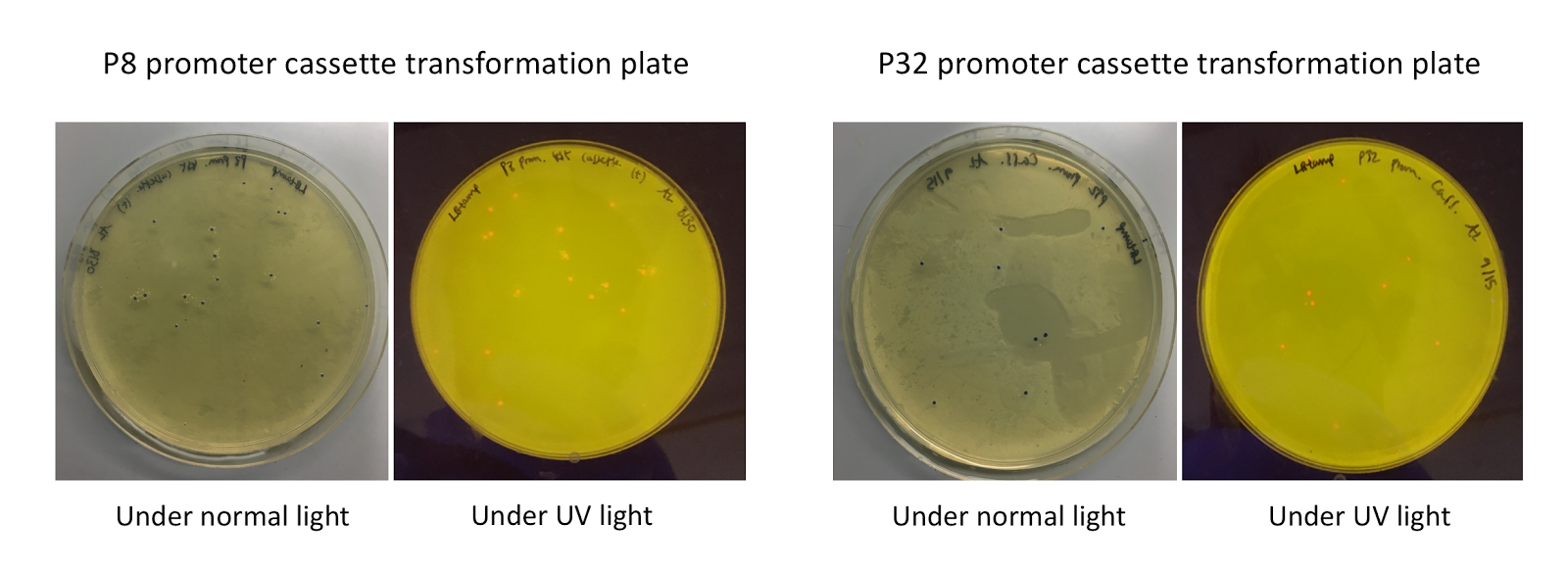

Upon first look, E. coli colonies transformed with these assemblies appeared purple-blue in color. This phenotype was due to the expression of the red fluorescent protein. Further, we noticed that E. coli colonies transformed with these assemblies fluoresced red under UV light, indicating that the P8 and P32 promoters are indeed expressing the E2-Crimson reporter gene and thus are functional in E. coli (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. P8/P32 test cassette plasmid transformation plates, under normal and UV lights. Under normal lights, the colonies appeared purple-blue in color. Under UV, the colonies fluoresced red.

Back to Top

Testing for gadB overexpression in E. coli

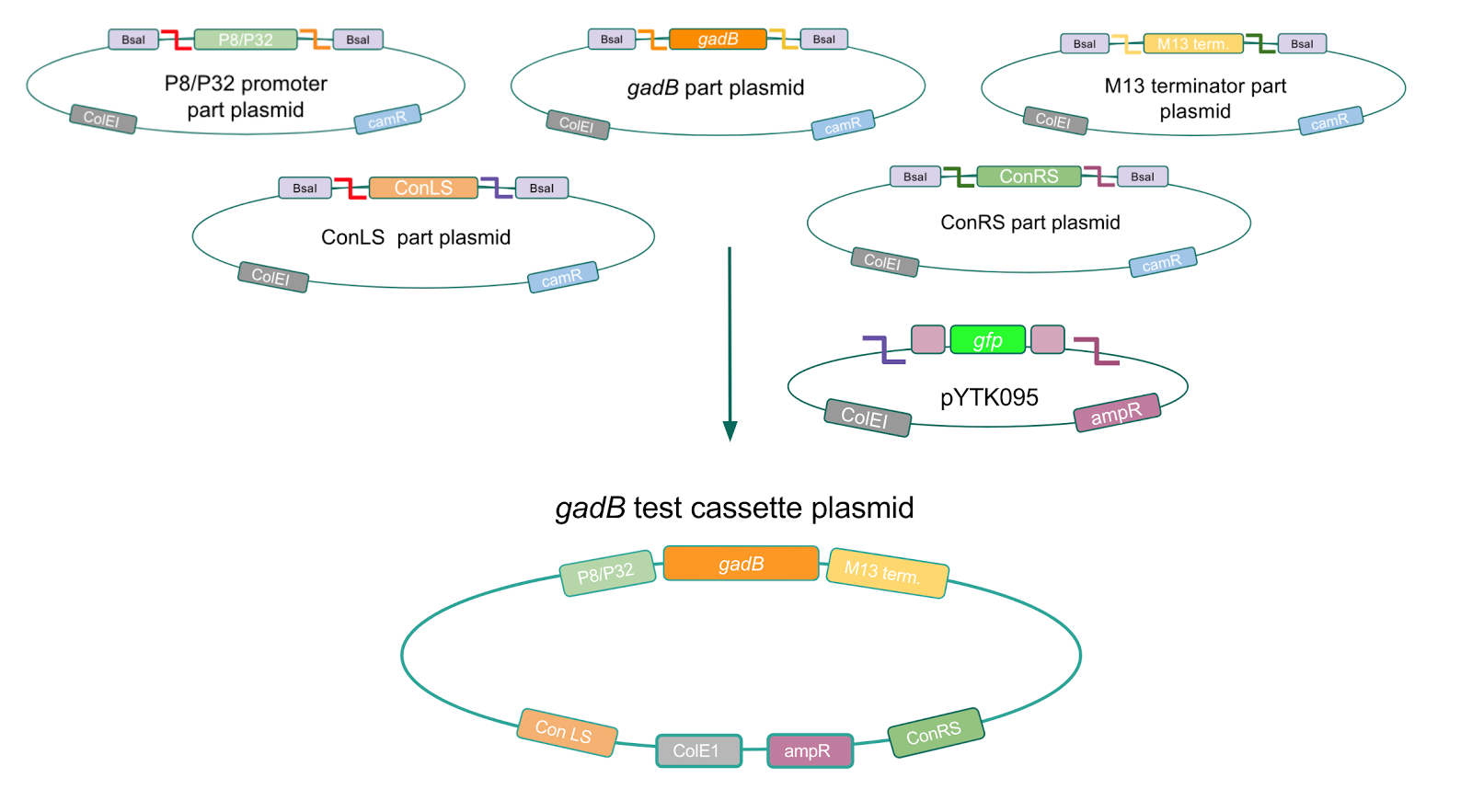

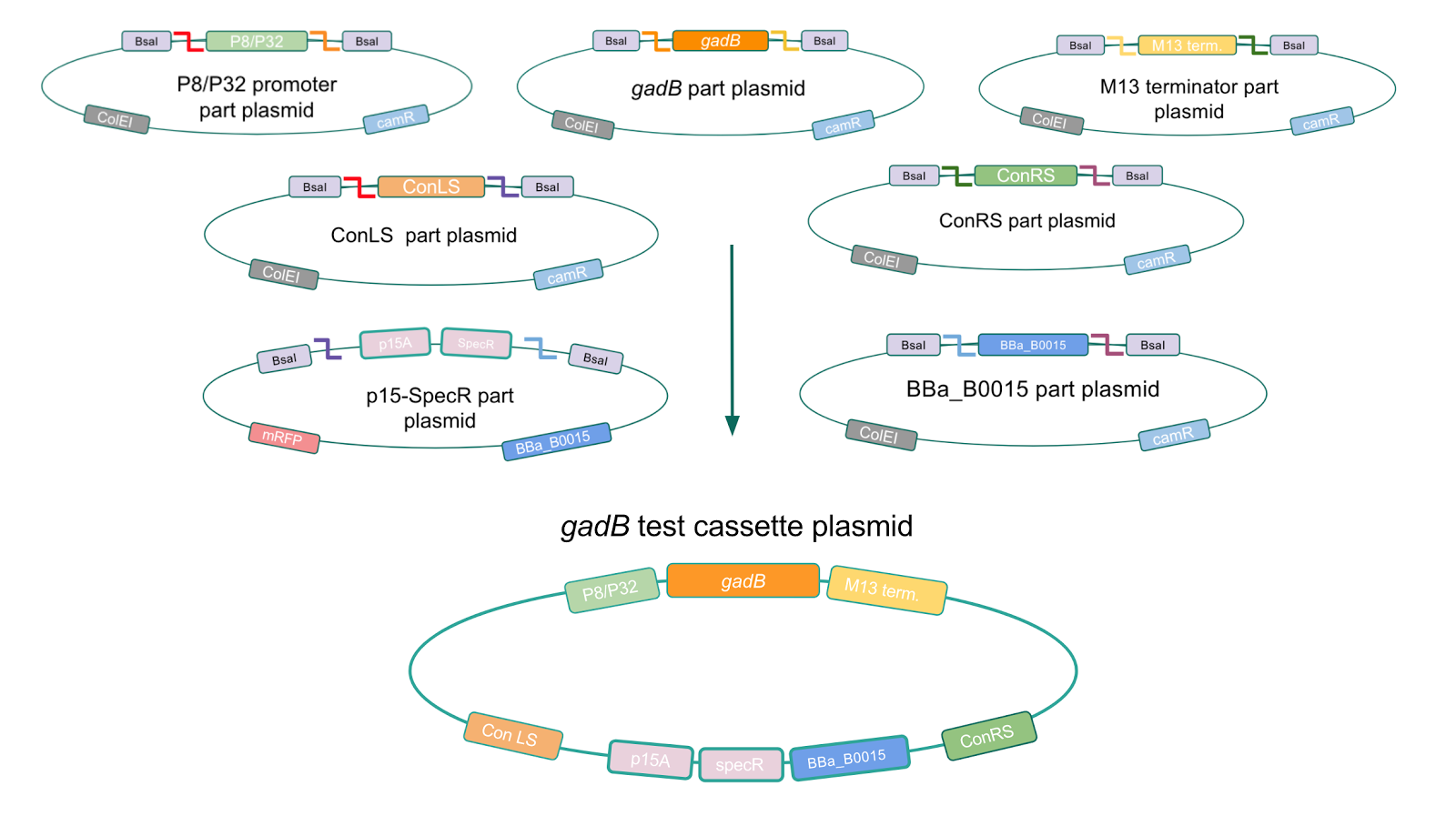

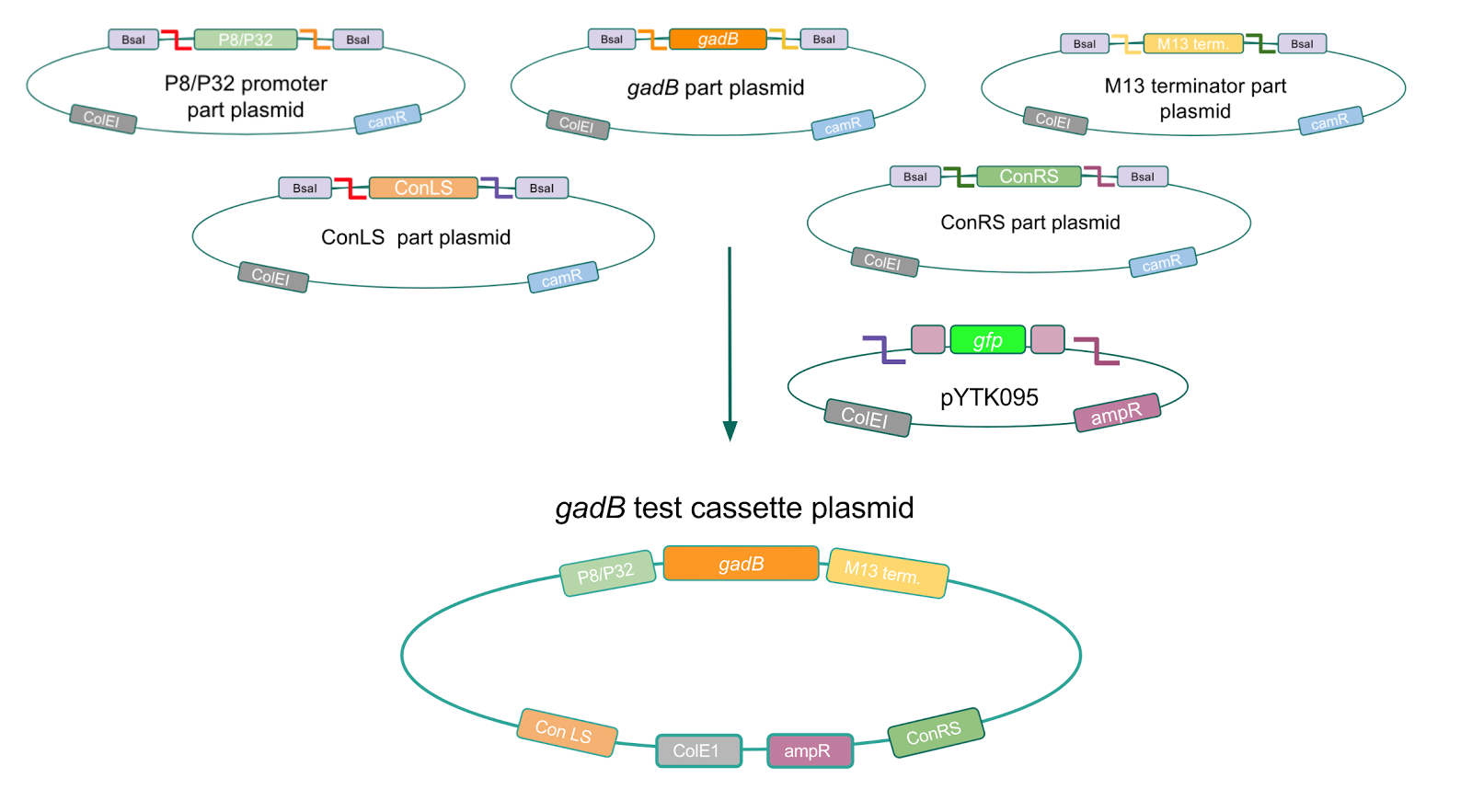

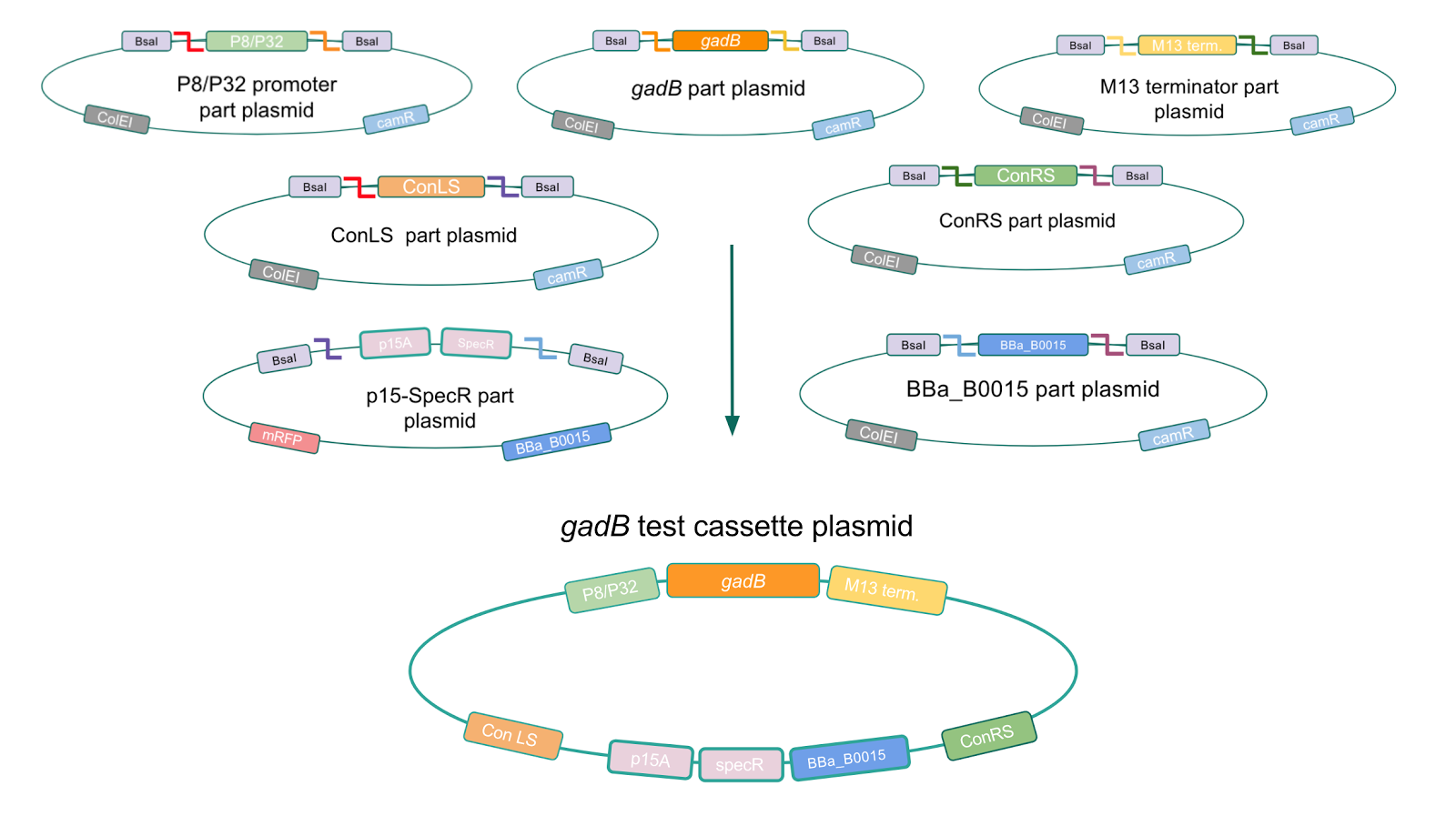

Using Golden Gate Assembly, we created cassette plasmids to test if the gadB gene could be overexpressed in E. coli via the P8 and P32 promoters. These cassette plasmids contained the gadB gene inserted downstream of either the P8 or P32 promoters. To make our gadB test cassette plasmids, we used pYTK095 as our backbone and part plasmids containing the P8/P32 promoters, gadB gene, M13 terminator, and connector sequences (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Golden Gate assembly process of P8/

gadB and P32/

gadB test cassette plasmids.

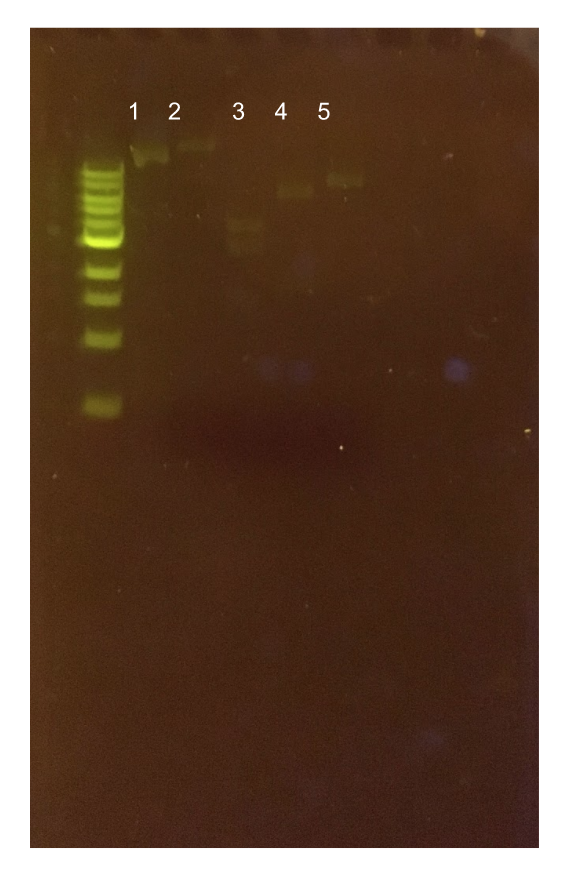

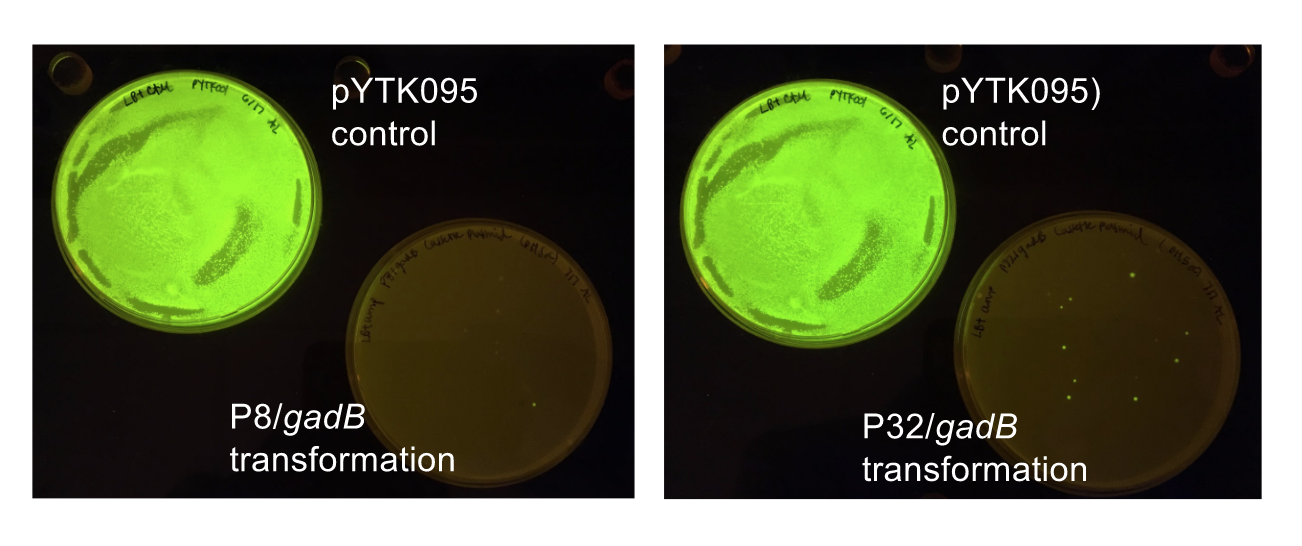

Similar to the pYTK001 entry vector in part assembly, the pYTK095 backbone used for cassette assembly contained a gfp reporter gene that is replaced by sequences of interest. This allowed us to easily perform a phenotypic screen for positive colonies. Non-fluorescent colonies may potentially have had the correct cassette assembly, while fluorescent colonies did not (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. P8/

gadB and P32/

gadB cassette E. coli transformations alongside a pYTK095 control transformation under UV illumination. Potentially positive colonies containing the correct assemblies appeared non-fluorescent, while negative colonies appeared fluorescent.

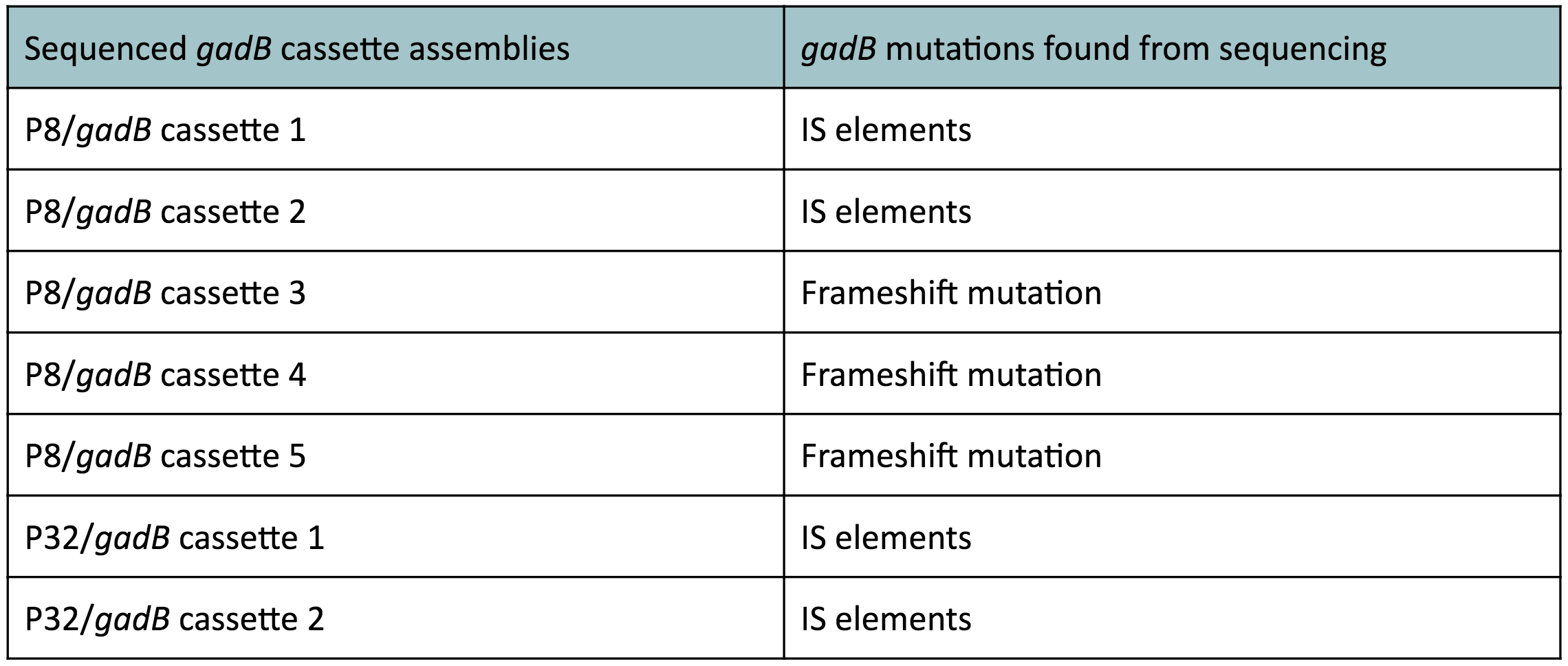

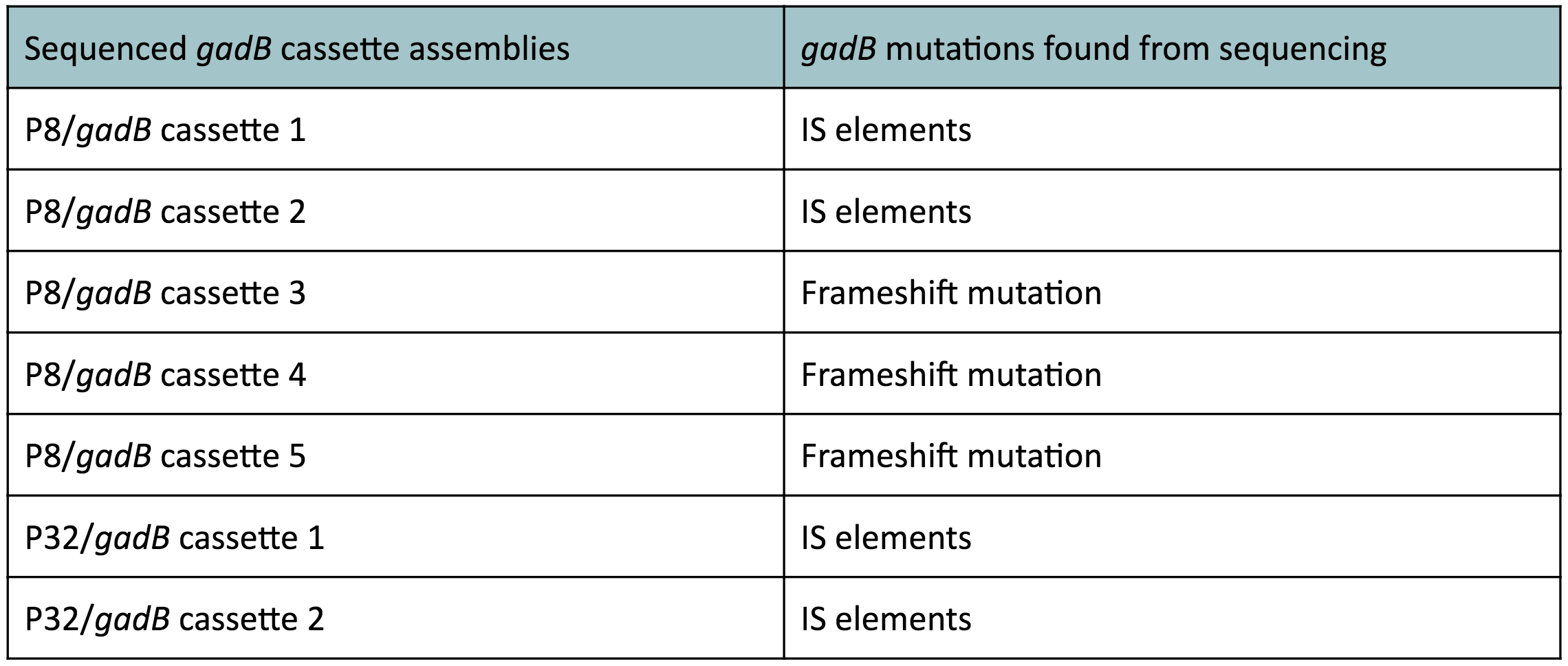

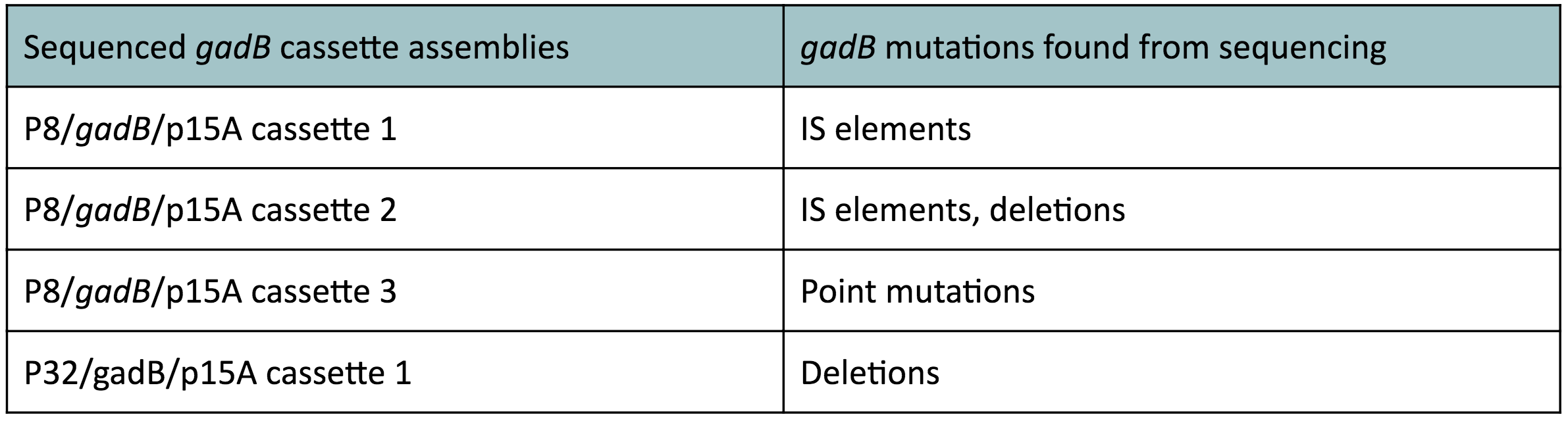

The non-fluorescent colonies were then screened using colony PCR, and positive colonies were then miniprepped and sequenced. The sequencing results indicated that there were several mutations within the gadB gene in the samples. These mutations are recorded in Table 1.

Table 1. gadB mutations in sequenced P8/

gadB and P32/

gadB overexpression cassette plasmids.

Along with being one of the canonical amino acids utilized in protein synthesis, glutamate plays an important role as the main amino-group donor in the biosynthesis of nitrogen-containing compounds such as amino acids and nucleotides (4, 5). Thus, we hypothesized that gadB overexpression via the P8 and P32 constitutive promoters and the high-copy number ColE1 origin induced a high metabolic load on the cells by shunting away glutamate from essential anabolic pathways. We believed that transformants containing the mutationally degraded gadB gene were selected for. In contrast, transformants containing the functional gadB gene were selected against due to having a depletion of glutamate substrates needed for important cellular processes.

To troubleshoot this problem, we decided to use a backbone containing the low-copy number p15A origin for the cassette assembly (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Golden Gate assembly process of P8/

gadB and P32/

gadB test cassette plasmids using a backbone containing the low-copy number p15A origin.

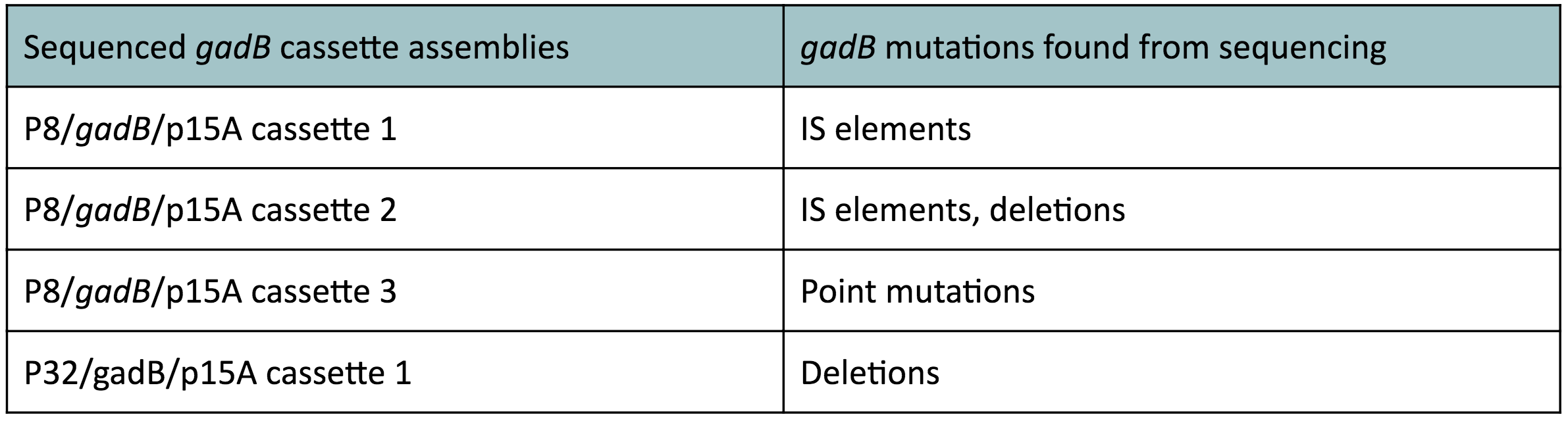

Copy number reduction of our gadB overexpression cassette plasmids (accomplished by replacing the ColE1 origin with the p15A origin) was expected to decrease the overall amount of gadB expression, thereby decreasing the metabolic load imposed on the cells and the mutation rates observed in the gadB gene. However, we also observed several mutations within the gadB gene in the potentially positive cassette plasmids sequenced. The observed mutations are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2 gadB mutations in sequenced P8/

gadB/p15A and P32/

gadB/p15A overexpression cassette plasmids.

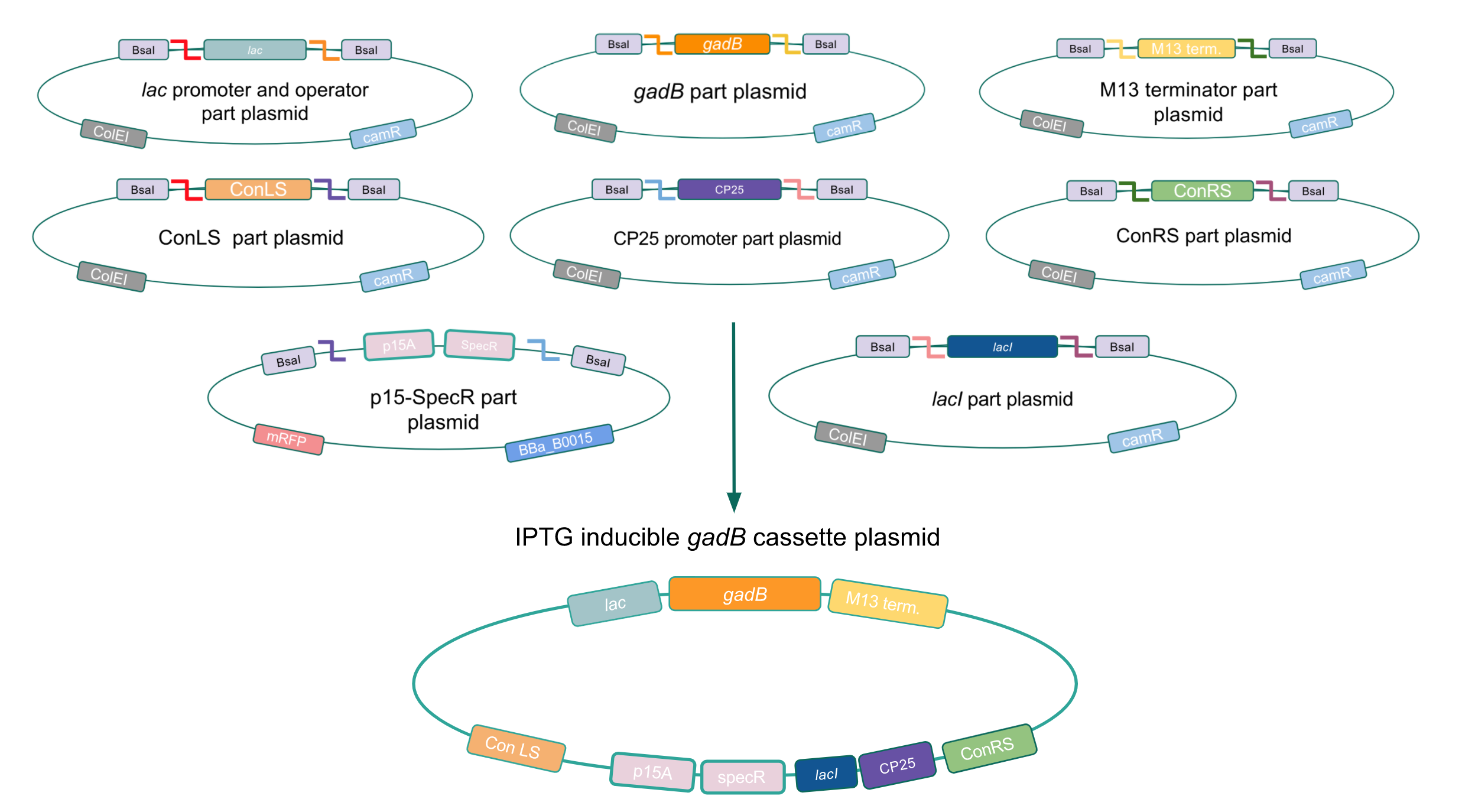

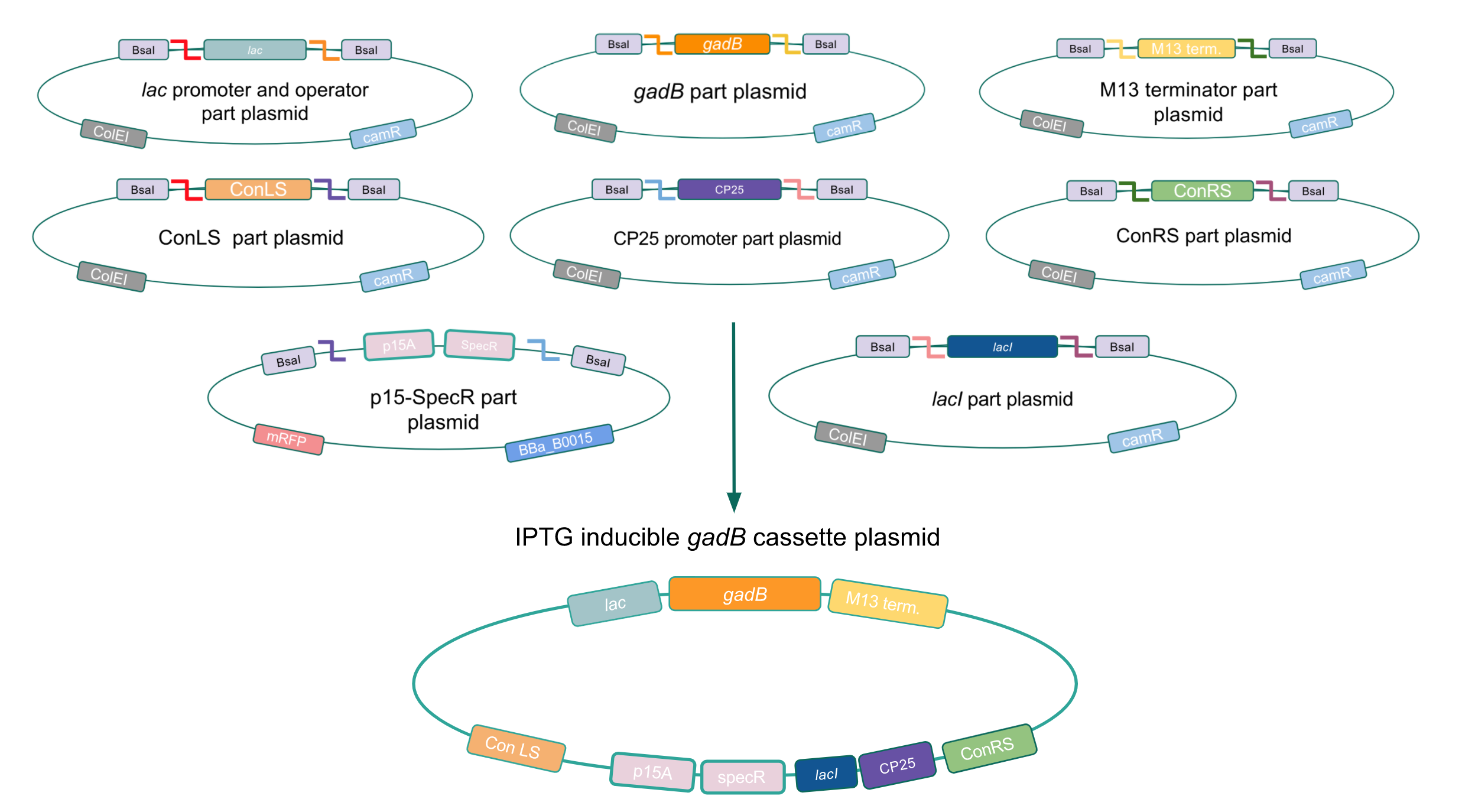

With our theory that gadBoverexpression was toxic to bacterial cells, we attempted to inducibly express the gadB gene using the regulatory elements of the lac operon to see if controlled gadB expression was even possible in E. coli. Our IPTG-inducible gadB expression cassette plasmid was assembled using a lac promoter and operator part plasmid, the gadB gene part plasmid, the M13 terminator part plasmid, connector part plasmids, a CP25 promoter part plasmid, a lacI part plasmid, and the SpecR and p15A origin part plasmid (Fig. 8). Under this assembled regulatory system, in the absence of IPTG (an analog of the allolactose inducer) the LacI repressor will bind to the lac operator region to block transcription of the gadB gene. When present, IPTG will act as an inducer and bind to the LacI repressor to decrease its binding affinity for the lac operator, thereby allowing for gadB expression. This IPTG-inducible system provides us with a mechanism of controlling gadB expression. Positive colonies have been identified and sequence verification is currently underway.

Figure 8. Golden Gate assembly process of IPTG-inducible

gadB expression cassette plasmid.

Back to Top

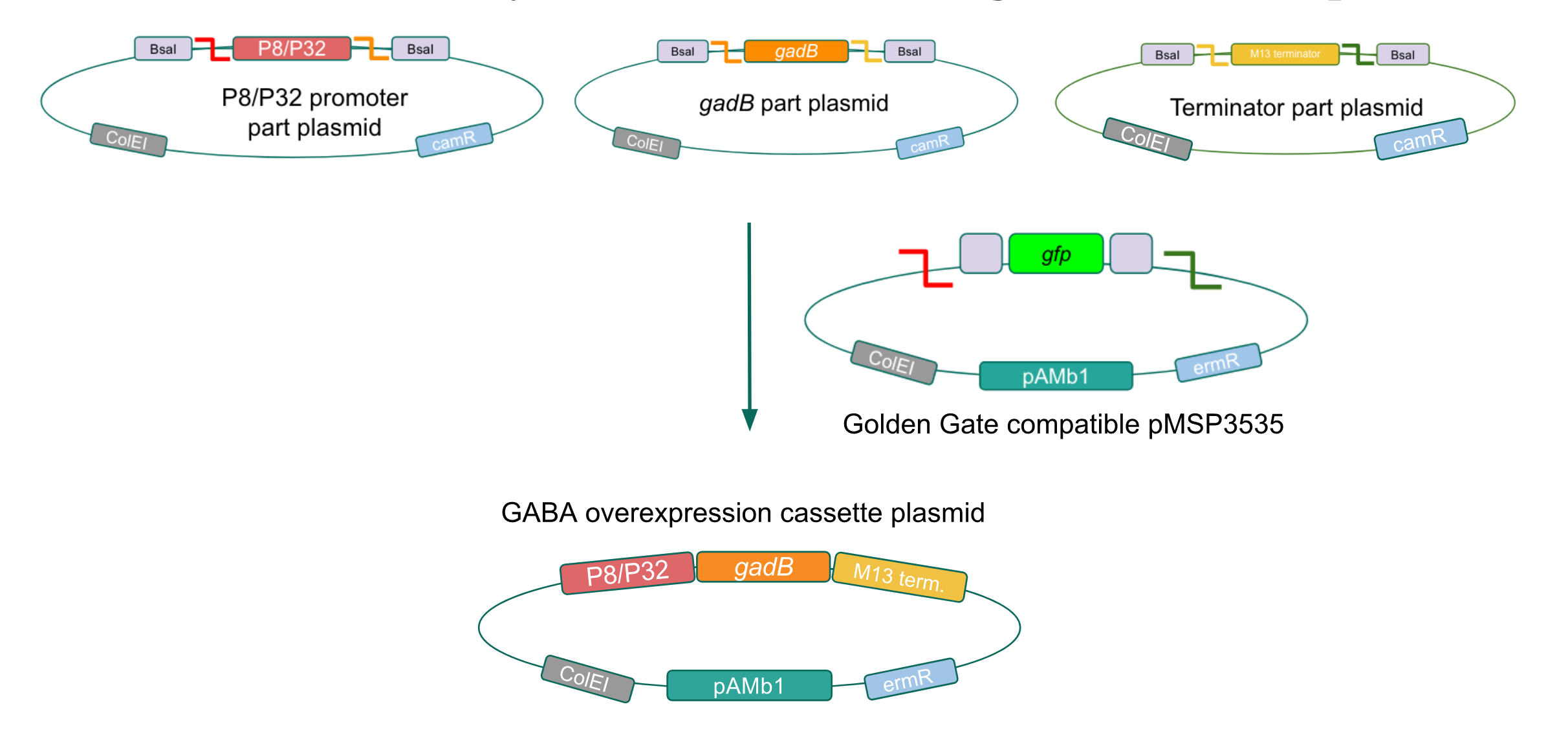

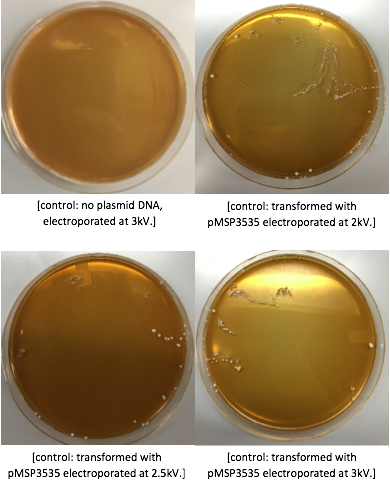

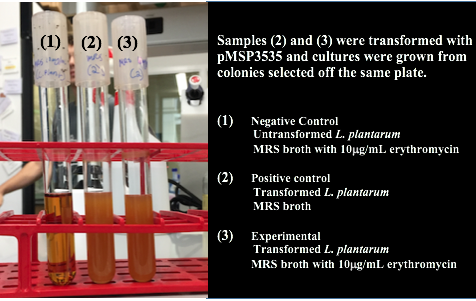

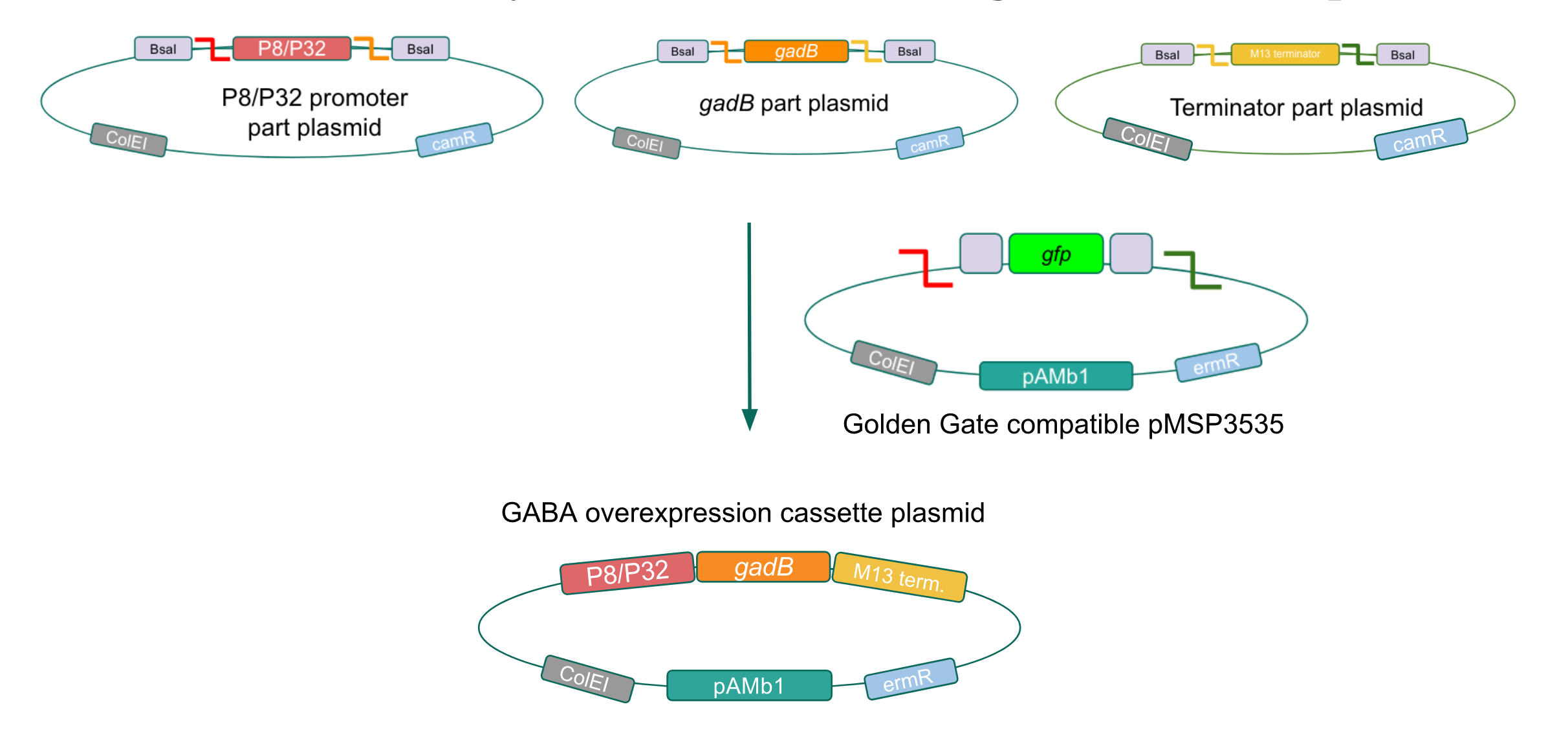

Creating a Golden Gate compatible shuttle vector

We wanted to assemble our final GABA overexpression cassette plasmid using the shuttle vector pMSP3535 as the backbone (Fig. 9). To do this, we first needed to make pMSP3535 Golden Gate compatible (i.e. free of BsaI restriction sites and containing correct overhangs for cassette assembly). We chose to work with pMSP3535 as it contains both a ColE1 origin for replication in E. coli and a pAMb1 origin for replication in Gram-positive bacteria including Lactobacillus species (6). Additionally, the pMSP3535 vector contains the resistance gene for erythromycin, of which Lactobacillus plantarum is naturally susceptible (7).

Figure 9. Golden Gate assembly of the GABA final overexpression cassette plasmid with the Golden Gate compatible pMSP3535 vector and the P8/P32 promoter,

gadB gene, and M13 terminator part plasmids.

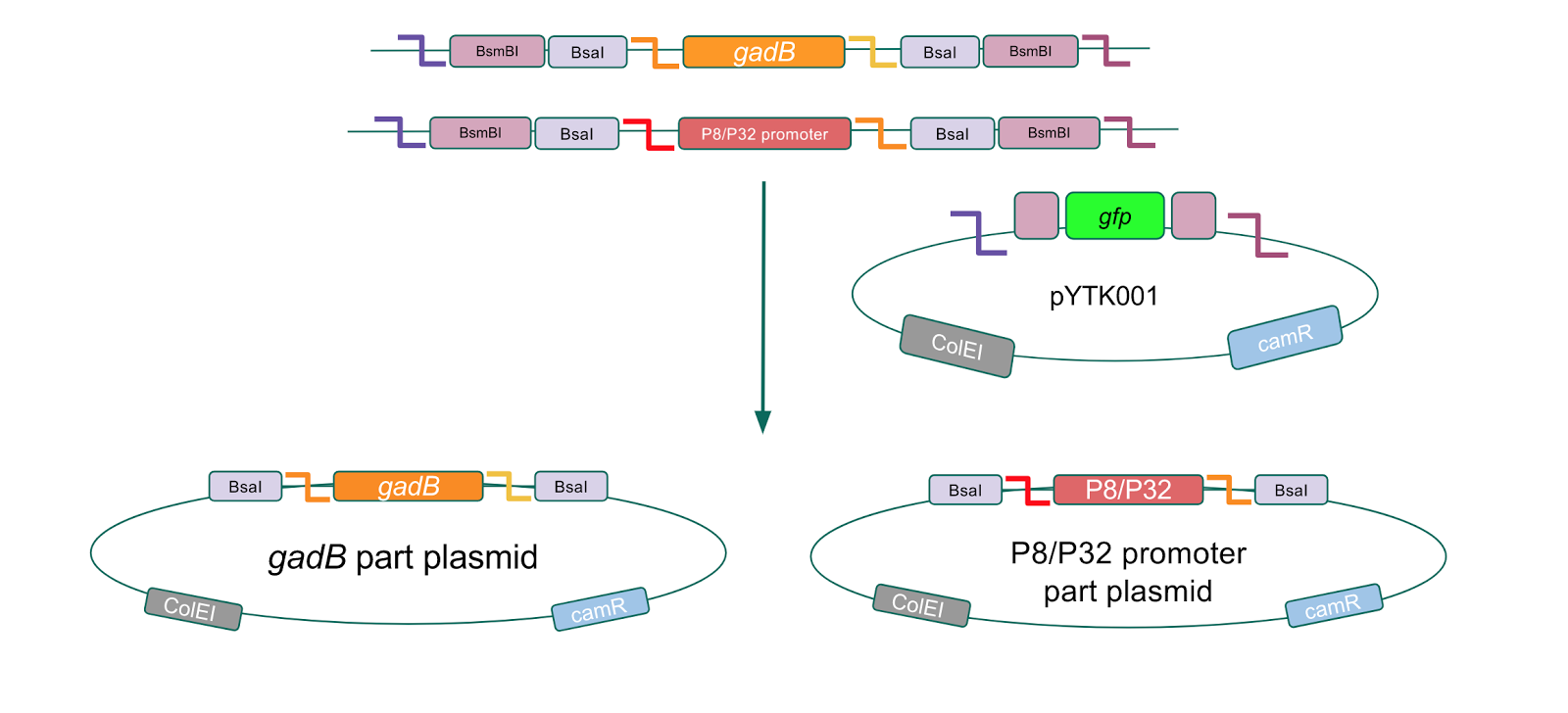

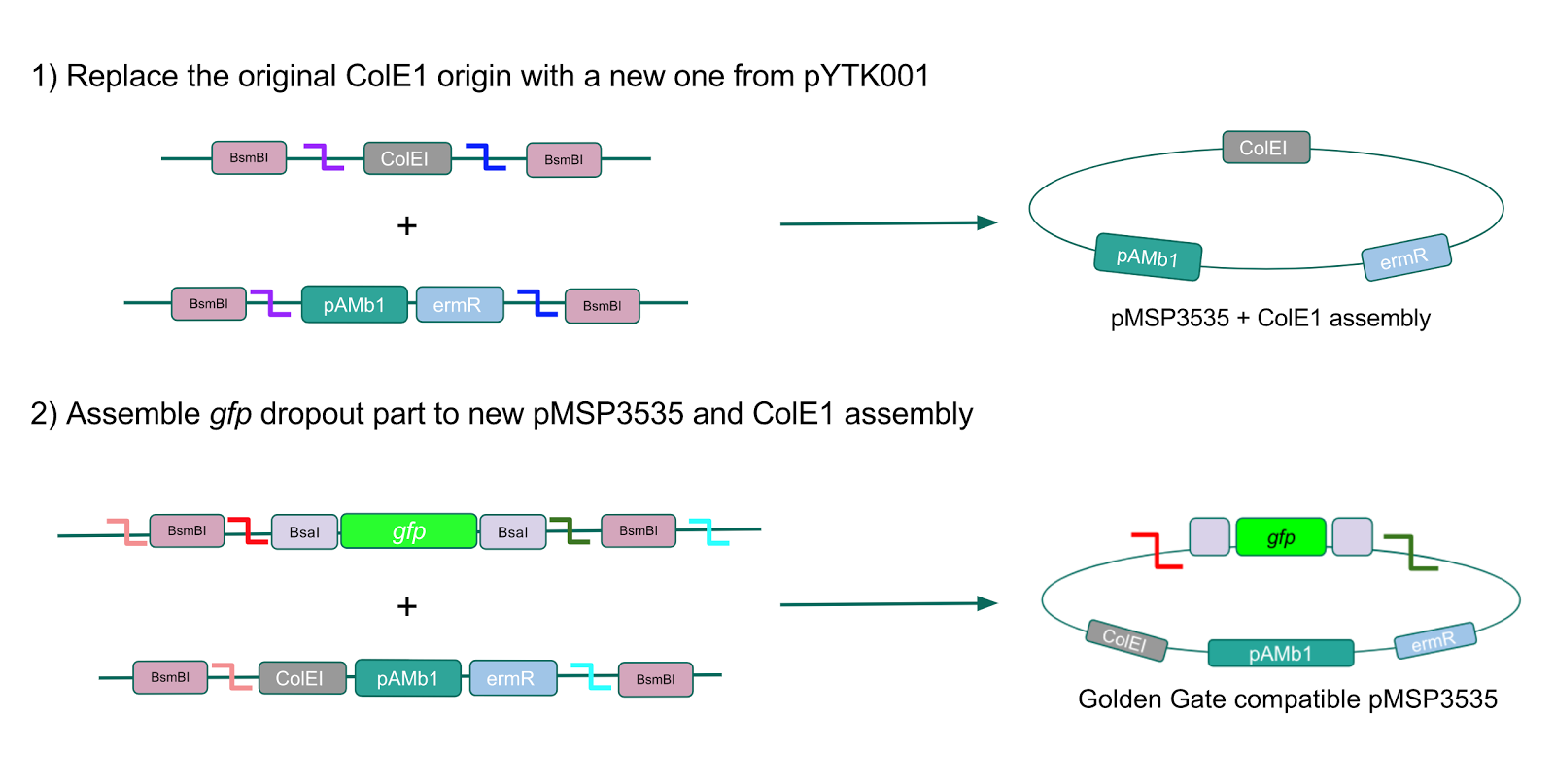

The process of making the pMSP3535 vector Golden Gate compatible involved two steps: 1) assembling the pMSP3535 backbone (pAMb1 origin and erythromycin resistance gene) with a new ColE1 origin; 2) assembling a gfp dropout part to the assembly of the pMSP3535 backbone and the new ColE1 origin (Fig. 10).

Figure 10. Assembly workflow for creating the Golden Gate compatible pMSP3535 backbone. The first step involves replacing the ColE1 origin in the pMSP3535 backbone with a new ColE1 origin from pYTK001 to create a pMSP3535 + ColE1 assembly. The second step involves combining the pMSP3535 + ColE1 assembly with a

gfp dropout to form the final Golden Gate compatible vector to be used to create our GABA overexpression plasmid.

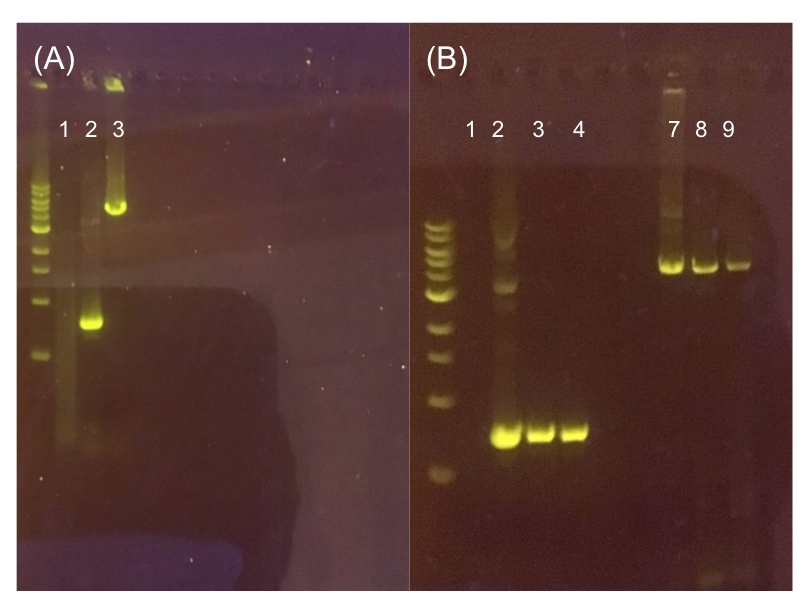

Figure 11. (A) Agarose gel of successful PCR for the pMSP3535 backbone and the ColE1 origin. Lane 1 contains a negative PCR control. Lanes 2 and 3 contain the ColE1 origin (around 800 bp) and pMSP3535 backbone PCR products (around 4.3 kb). (B) Agarose gel of diagnostic PCR of miniprep samples from pMSP3535 + ColE1 transformants. Lane 1 contains a negative PCR control. Lane 2 contains a positive PCR control for the pMSP3535 backbone, while lanes 3 and 4 contain the pMSP3535 PCR from two miniprep samples. Lane 7 contains a positive PCR control for the ColE1 origin, while lanes 8 and 9 contain the ColE1 PCR from the same two miniprep samples. Evidently, the pMSP3535 backbone and ColE1 origin is present in both tested miniprep samples.