Our Model for our project started out with the sole objective of proving through simulation the viability of our idea. After the realization of the possibilities that we could achieve through the tools that we had available we wanted to use our model to be able to make our whole system more efficient. All our modelling was made possible through Mathwork’s Matlab, specifically with the SimBiology toolbox.

Viability

To prove if our project was plausible we started out by considering the kinetics of the channels and transporters which we wanted to transform into our organism Saccharomyces cerevisiae. As we had different types of integrated proteins also different types of kinetic mechanism had to be considered. This were specifically: channels, antiporters, transporters and even not characterized efflux und influx from the organism itself. In the following section, we will go into detail how the mechanisms work.

Channels

GEF1-Cl

The native channel GEF1 was characterized as a chloride voltage-gated channel (Flis et al. 2002)

with a conductivity of

42 ± 4 pS. With a high voltage tolerance, the channel remains mostly in the open state.

As a channel, a direct Michaelis–Menten kinetic was assumed. The definition of its constants vmax and Km are defined for the

Simulation as it follows:

The equation that represents the chloride current can be taken from Ohm’s law:

Where V represents the voltage varying from -50 to – 120 mV (Vacata et al. 1981) G is the conductivity of the channel and I the current in C/s. The current still must be converted into a reaction rate. To this end the charge of chloride was assumed as it’s one valence electron. Through the next equation the rate was then calculated and incorporated into the model:

Here two natural constants describe the relationship between the electron current and the molecular current. NA represents the Avogadro’s Number, which states the relationship between molecules per mole. e the elementary charge of an electron, in this case Cl-.

As no other membrane protein was found to be strongly responsible for the intake of Chloride and GEF1 was found to be ubiquitous to all compartments in the cell (López-Rodríguez et al. 2007). The same kinetics of the GEF1 channel were then assumed from the influx of Cl- although with a different vmax (Roberts et al. 2001) as the surface area is increased and the protein number is reduced.

This lead to the voltage dependant Michaelis-Menten kinetic equation:

Km is the substrate concentration by which the reaction achieves the half of its maximal reaction rate, while [Cl- out] is the chloride concentration and v the reaction rate. The value of Km is 93 ± 32 mM (Roberts et al. 2001).

Uniporters

AVP1 – H+, GmSULTr1;2 – SO32-, AKT1 – Na+

AVP1, GmSULTr1;2 and AKT1 have been characterized as Transporters from H+ , SO32- and Na+ respectively

(Drozdowicz et al. 2000),

(Ding et al. 2016), (Pyo et al. 2010).

Their kinetics can be easily explained through the following model (Beard, Qian 2008; Pradhan et al. 2010):

For the Uniport reaction this can be sketched on the following flow chart:

The overall reaction can be stated in the following chemical reaction:

Throughout the reaction the enzyme goes through the 4 different states 1 -> 2 -> 3 -> 4 -> 1. On each state, there is a specific concentration of enzymes, this can be represented through es1, e2, e3, e4. This leads to the following relation in equilibrium state:

To calculate the equilibrium constant Keq, the free Gibbs Energy formula can be used:

As the educts and products are thermodynamically equal it is feasible to assume that ΔG0 = 0. As all our uniporters transport one ion per transport process the equation can be simplified with the Reaction Quotient Q to:

In equilibrium is ΔG = 0 and Q = Keq. Therefore, the final equation for our equilibrium constant can be calculated for cation uniporters through the following equation:

It is due to note that for electroneutral transporters, the equation would equal 1, thus simplifying the kinetic process. We assume that the change of potential is through the inclusion of ions in the vacuole near 0, because the influx of opposite charged ions follows directly.

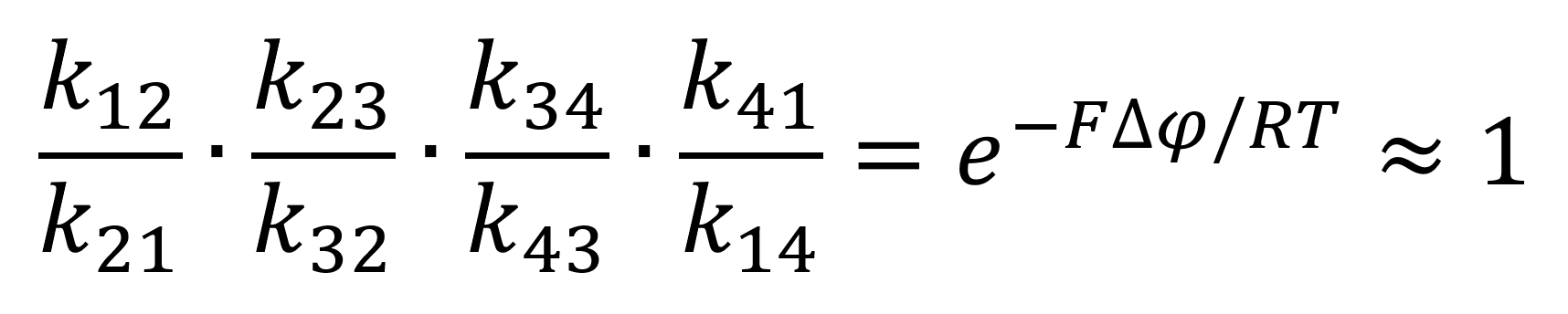

Using the newly found equilibrium constant equation 4 can be represented through the mass-action rate constants as follows:

Through the assumption of rapid equilibrium, in which both the unbinding and binding of the substrates are rapid thus making the constricting states of the enzymes both e2 and e3. This relationship can be expressed through the following equations:

Whereby Kd = k12/k21 = k23/k32 is the dissociation constant from the enzyme at both the binding and unbinding site. Through this assumption equation 8 can be simplified to:

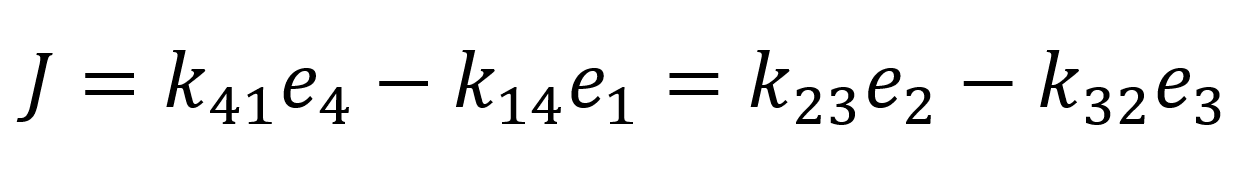

Next, we introduce the assumption that the protein does not undergo any conformational transformations in the process of the transport of the bounded protein. Thus, to fulfil equation 9 k23 = k14 = k+ and k32 = k14 = k- must follow. Through the conservation of total protein and the flux quasi-steady approximation:

We can determine the values of e4 and e1 and substitute them into the flux equation:

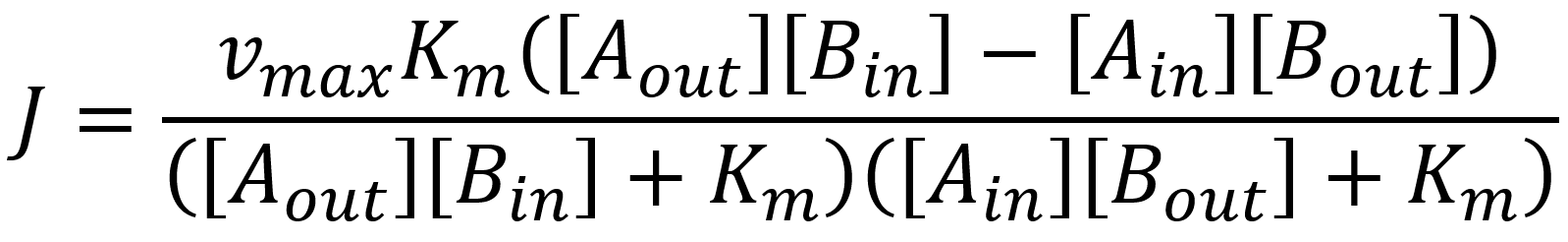

As we assumed rapid equilibrium it also follows that Kd = Km therefore we can summarize our flux equation as follows:

Equation 11 is the one which we used in Matlab’s tool symbiology to define our flux rates.

Antiporters

NHX1 - Na+/H+, AtNHXS1 - Na+/H+

Both Antiporters that we simulated in our model where fuelled by the proton and cation gradient that we wanted to build up. Therefore, both were coupled with the already expressed AVP1 channel.

We choose AtNHXS1 as it had a higher affinity to Na+/H+, we also wanted to prove with its inclusion if the vacuole Na+ content would increase (Xu et al. 2010; Yamaguchi et al. 2003). As well as an overexpression of NHX1 to increase the total flux of Sodium in for example prevacuolar compartments as it is in comparison to AtNHXS1 localised in more compartments besides the vacuole (Darley et al. 2000; Nass et al. 1997).

As for the kinetic, we can use the previous stated model with the modification that two substrates bind and unbind:

Therefore, following chemical reactions can be summarized as:

This allows us once again to simplify the reaction as 2 single reactions and define once again through the rapid equilibrium assumption that:

Following the same path as for our uniporters we come to the flux expression of:

The following table includes the different kinetic constants of the uniporters and antiporters that we included in the model.

Na+ Influx

For both the Na+ Influx as it depends on a complex of diffusion and different transport mechanisms we assumed a single substrate Michaelis-Menten mechanism with competitive inhibition through the substrate on the cytosolic side. (Armstrong 1967; Borst-Pauwels 1981)

The found constants for the Na+ Influx were found to be:

Cl- Influx

As well as the Sodium influx it is a complex mechanism that regulates the Cl- Influx. According to (Wada et al. 1992) the mechanism of the Cl- influx is regulated through the following flux:

The constants for this flux were found to be:

Yeast Characteristics

pH Value

An important value that we had to include in the model was the distribution of the pH on the yeast itself, because it is the driving force of our exchange into the compartments. In accordance to (Valli et al. 2005) a linear regression was found between the external pH and the cytosolic pH. This is expressed through the next equations for the exponential and stationary phases respectively.

Membrane Potential

As our channels are also Potential dependent (specially GEF1). The Membrane Potential had also to be defined. This was assumed as a constant and the values for it were taken from (Vacata et al. 1981).

Yeast Weight

As our channels are also Potential dependent (specially GEF1). The Membrane Potential had also to be defined. This was assumed as a constant and the values for it were taken from (Vacata et al. 1981).

Efficiency improvement

To prove the efficiency of our model we made parameter Sweeps and checked the result kinetics. This to be able to give a forecast of how in industrial applications could be more efficient where these parameters can be more regulated. The results obtained from our model are the following:

0,6M / 6.6 pH / -120mV

0,9M / 6.0 pH / -70mV

2,5M / 5.5 pH / -55mV

Armstrong, W. McD. (1967): Discrimination between Alkali Metal Cations by Yeast. II. Cation interactions in transport. In The Journal of general physiology 50 (4), pp. 967–988. DOI: 10.1085/jgp.50.4.967.

Beard, Daniel A.; Qian, Hong (2008): Chemical biophysics. Quantitative analysis of cellular systems / Daniel A. Beard, Hong Qian. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (Cambridge texts in biomedical engineering). Available online at http://www.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0808/2007051292-b.html.

Borst-Pauwels, G. W. (1981): Ion transport in yeast. In Biochimica et biophysica acta 650 (2-3), pp. 88–127.

Darley, C. P.; van Wuytswinkel, O. C.; van der Woude, K.; Mager, W. H.; Boer, A. H. de (2000): Arabidopsis thaliana and Saccharomyces cerevisiae NHX1 genes encode amiloride sensitive electroneutral Na+/H+ exchangers. In The Biochemical journal 351 (Pt 1), pp. 241–249.

Ding, Yiqiong; Zhou, Xiaoqiong; Zuo, Li; Wang, Hui; Yu, Deyue (2016): Identification and functional characterization of the sulfate transporter gene GmSULTR1;2b in soybean. In BMC genomics 17, p. 373. DOI: 10.1186/s12864-016-2705-3.

Drozdowicz, Yolanda M.; Kissinger, Jessica C.; Rea, Philip A. (2000): AVP2, a Sequence-Divergent, K + -Insensitive H + -Translocating Inorganic Pyrophosphatase from Arabidopsis. In Plant Physiol. 123 (1), pp. 353–362. DOI: 10.1104/pp.123.1.353.

Flis, Krzysztof; Bednarczyk, Piotr; Hordejuk, Renata; Szewczyk, Adam; Berest, Vladimir; Dolowy, Krzysztof et al. (2002): The Gef1 protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is associated with chloride channel activity. In Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 294 (5), pp. 1144–1150. DOI: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00610-1.

HADDAD, S. A.; LINDEGREN, C. C. (1953): A method for determining the weight of an individual yeast cell. In Applied microbiology 1 (3), pp. 153–156.

López-Rodríguez, Angélica; Trejo, Alfonso Cárabez; Coyne, Leanne; Halliwell, Robert F.; Miledi, Ricardo; Martínez-Torres, Ataúlfo (2007): The product of the gene GEF1 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae transports Cl- across the plasma membrane. In FEMS yeast research 7 (8), pp. 1218–1229. DOI: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2007.00279.x.

Nass, Richard; Cunningham, Kyle W.; Rao, Rajini (1997): Intracellular Sequestration of Sodium by a Novel Na + /H + Exchanger in Yeast Is Enhanced by Mutations in the Plasma Membrane H + -ATPase. In J. Biol. Chem. 272 (42), pp. 26145–26152. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26145.

Pradhan, Ranjan K.; Beard, Daniel A.; Dash, Ranjan K. (2010): A biophysically based mathematical model for the kinetics of mitochondrial Na+-Ca2+ antiporter. In Biophysical journal 98 (2), pp. 218–230. DOI: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.10.005.

Pyo, Young Jae; Gierth, Markus; Schroeder, Julian I.; Cho, Myeon Haeng (2010): High-affinity K(+) transport in Arabidopsis. AtHAK5 and AKT1 are vital for seedling establishment and postgermination growth under low-potassium conditions. In Plant Physiol. 153 (2), pp. 863–875. DOI: 10.1104/pp.110.154369.

Roberts, Stephen K.; Dixon, Graham K.; Fischer, Marc; Sanders, Dale (2001): A Novel Low-Affinity H+-Cl- Co-Transporter in Yeast. Characterization by Patch Clamp. In Mycologia 93 (4), p. 626. DOI: 10.2307/3761817.

Vacata, V.; Kotyk, A.; Sigler, K. (1981): Membrane potentials in yeast cells measured by direct and indirect methods. In Biochimica et biophysica acta 643 (1), pp. 265–268.

Valli, Minoska; Sauer, Michael; Branduardi, Paola; Borth, Nicole; Porro, Danilo; Mattanovich, Diethard (2005): Intracellular pH distribution in Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell populations, analyzed by flow cytometry. In Applied and environmental microbiology 71 (3), pp. 1515–1521. DOI: 10.1128/AEM.71.3.1515–1521.2005.

Wada, Yoh; Ohsumi, Yoshinori; Anraku, Yasuhiro (1992): Chloride transport of yeast vacuolar membrane vesicles. A study of in vitro vacuolar acidification. In Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenergetics 1101 (3), pp. 296–302. DOI: 10.1016/0005-2728(92)90085-G.

Xu, Kai; Zhang, Hui; Blumwald, Eduardo; Xia, Tao (2010): A novel plant vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter gene evolved by DNA shuffling confers improved salt tolerance in yeast. In The Journal of biological chemistry 285 (30), pp. 22999–23006. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M109.073783.

Yamaguchi, Toshio; Apse, Maris P.; Shi, Huazhong; Blumwald, Eduardo (2003): Topological analysis of a plant vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter reveals a luminal C terminus that regulates antiporter cation selectivity. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100 (21), pp. 12510–12515. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2034966100.