Contents

Overview

Fluorescence is a commonly used method for detecting and quantitating gene expression. The InterLab study aims to create a more uniform way of measuring fluorescence so that results from different labs can be compared. The results in this study will be collated with all other results for the InterLab study by iGEM HQ. From the results, it is seen that J23101 is the strongest promoter followed by J23106 and J23117 being the weakest, and B0034 is the stronger of the two ribosome binding sites with J364100 being the weaker. Additionally, we chose to investigate how commercial DH5α Escherichia coli derivatives and dimerization of plasmids can affect gene expression, full methodology and results for this can be seen on the Measurement page.

Introduction

The InterLab study has been run by iGEM for the past 4 years. It aims to make science more replicable by creating more standardised methods that can be used by any research group with any equipment so that results can be more easily compared. This year the target of the study was to make a more standardised protocol for measuring fluorescence.

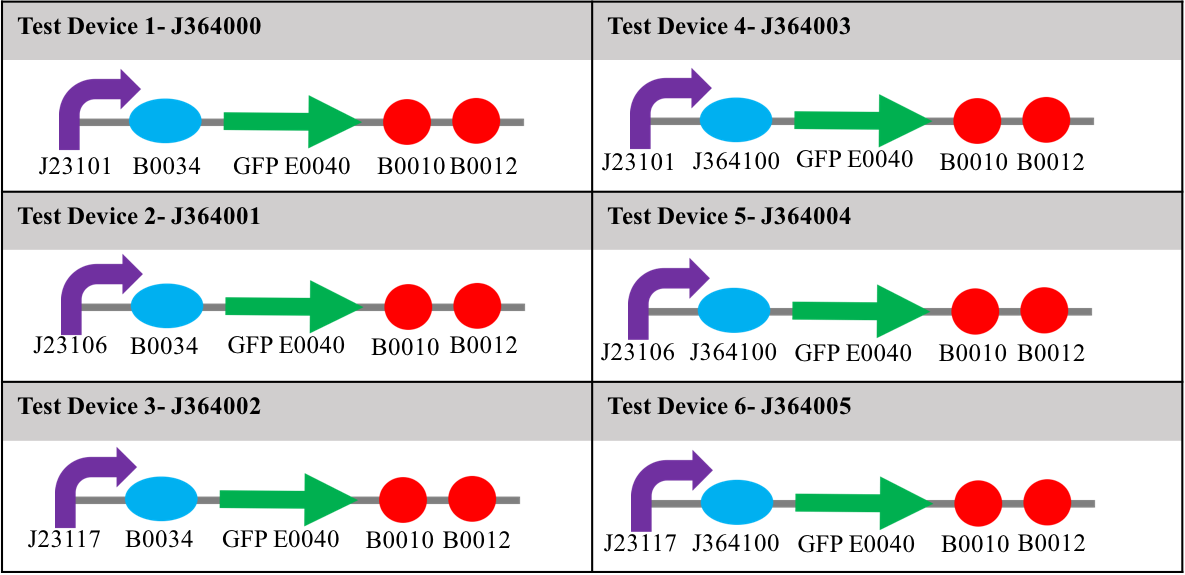

For the purpose of the InterLab study, 6 test devices were used, there were [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_J364000 J364000], [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_J364001 J364001], [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_J364002 J364002], [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_J364003 J364003], [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_J364004 J364004] and [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_J364005 J364005].

Each device contained one of three different promoters, and one of two different ribosome binding sites upstream of a gene for green fluorescent protein (E0040) and two terminators (B0010 and B0012). The promoters used in the study were: J23101 (strong); J23106 (medium); and J23117 (weak). The ribosome binding sites (RBS) used were; B0034; and J364100 (an element designed by Mutalik et al [1]). The relative strengths of these two ribosome binding sites were not known at the start of this study. Diagrams showing the constituent parts of each test device can be seen in table 1. Along with these six devices, were a positive and negative control, the positive being [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_I20270 I20270] – contains the J23151 promoter, B0032 ribosome binding site, E0040 gfp gene, B0010 terminator and the B0012 terminator- and [http://parts.igem.org/Part:BBa_R0040 R0040] –tetR repressible promotor with no gfp gene, which will not express GFP-. All devices used for testing were in the pSB1C3 plasmid and transformed into DH5α E. coli.

Materials and Methods

Transformations

These were carried out as per our standard calcium chloride protocol.

Calibration

Both the OD600 reference point and the fluorescein fluorescence standard curve were carried out as per the InterLab 2017 Plate Reader Protocol [2].

Measurements

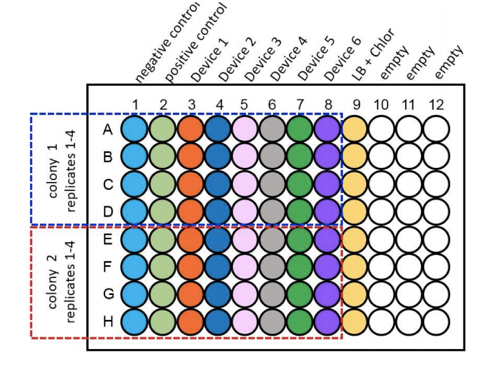

For the purpose of the measurements two biological duplicates (colonies) of all 6 test devices were transformed into DH5α, along with a positive and negative control and were grown up in LB broth overnight at 37°C with shaking at 220rpm. These were then diluted down to an OD600 of 0.02 and 100µl of the samples were placed into wells of a clear bottomed black sided 96 well plate as shown as per figure 1. This was placed into the plate reader at 37°C with shaking at 200rpm. Measurements of OD600 and Fluorescence at an excitation of 485nm and emission of 530nm were taken at time points of 0hrs, 2hrs, 4hrs and 6hrs.

Results

In order to measure and compare fluorescence in all test devices, these were transformed into DH5α E. coli. They were then checked via digestion and ran on a gel to verify size and to ensure that all plasmids were in monomer form. Once all the parts had been verified, 2 single colonies were picked from each test device and the fluorescence and OD600 for each was measured in the plate reader.

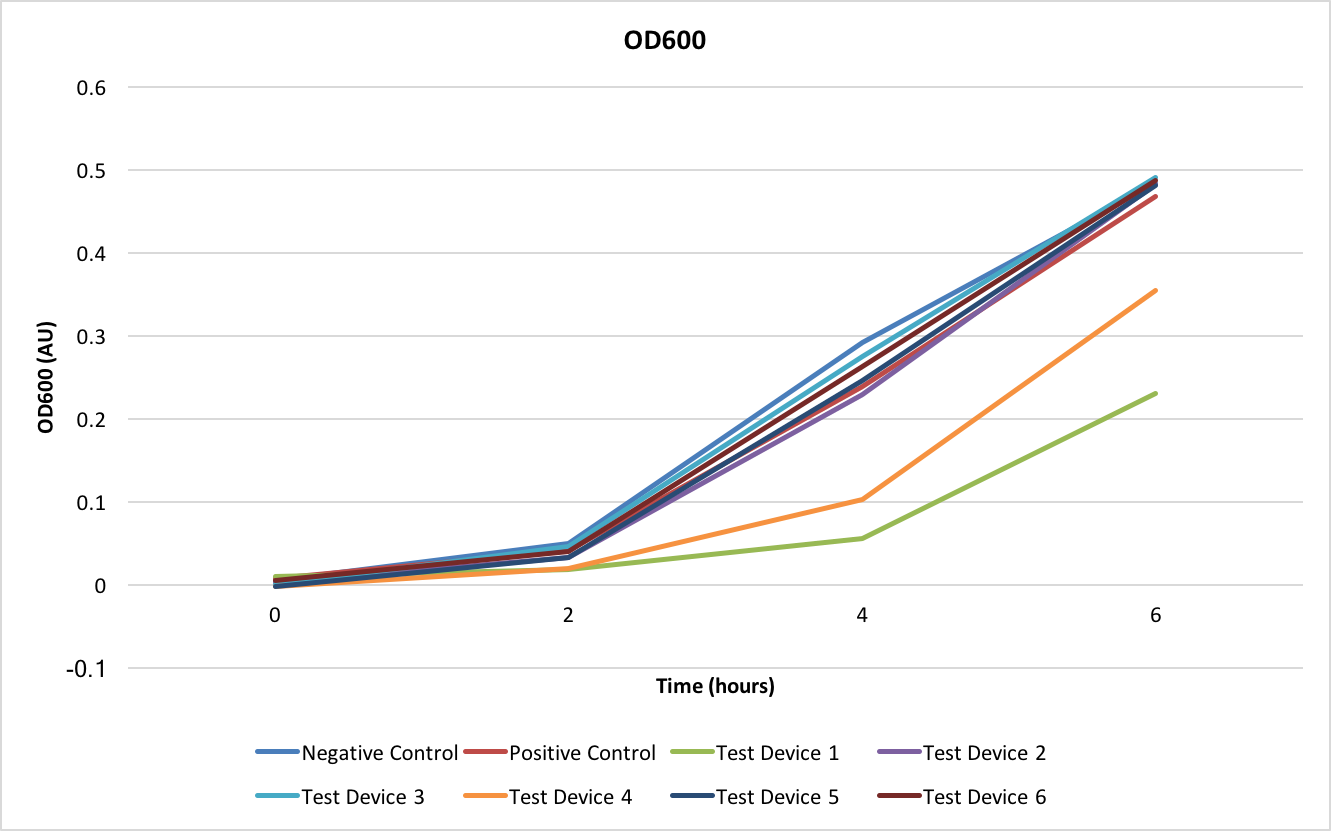

Growth

The OD600 shows how well the E. coli are growing with each of the different test devices. As can be seen from Figure 2, all test devices are growing at the same rate except for test devices 1 and 4- these two test devices share the J23101 promoter.

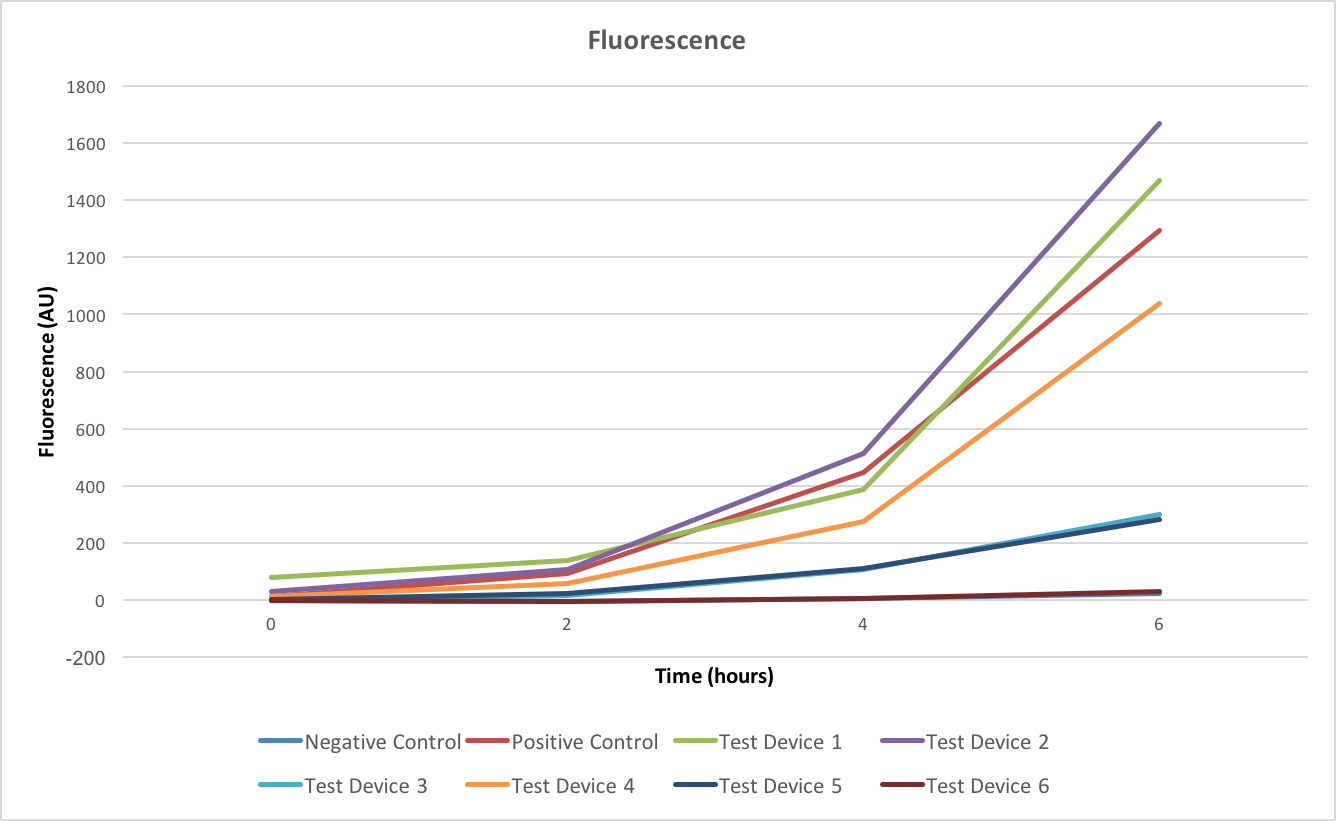

Fluorescence

Fluorescence shows the gene expression levels of GFP, from figure 3 it is shown that in all cases the fluorescence is increasing over time. However as this doesn’t take into account the differing growth rates of the test devices this doesn’t allow us to make any meaningful conclusions about the relative intensities of the test devices and so the efficiency of the promoters and ribosome binding sites.

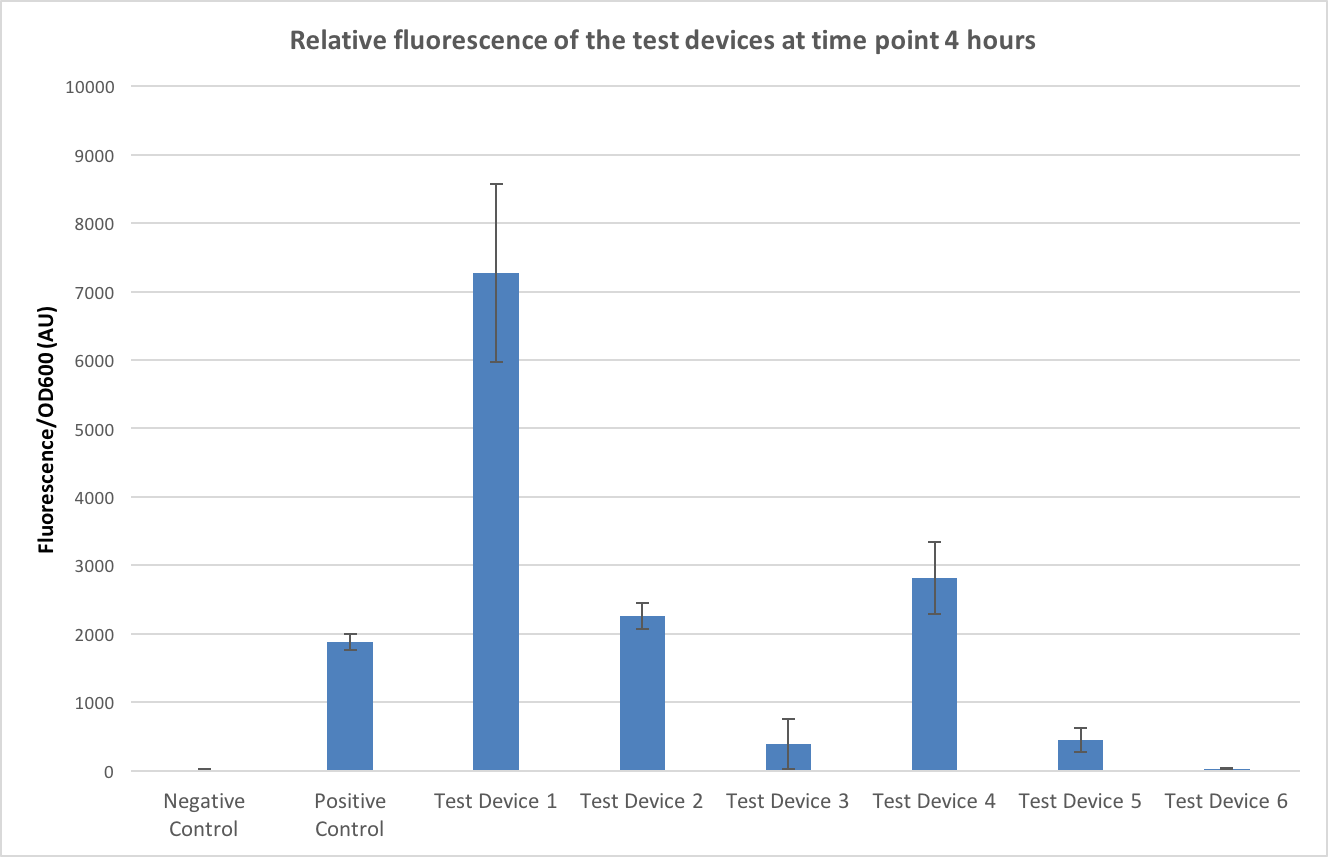

To allow conclusions to be made the fluorescence values were normalised to OD600, a graph of this can be seen in figure 4. The time point of 4 hours was chosen as this minimised any large standard deviations (due to dividing by very small numbers in the first few time points) and negative values caused by the background. The controls have worked- no fluorescence is seen in the negative control and fluorescence is seen in the positive controls- and it appears that test device 1 is the strongest out of all the test devices.

Firstly, looking at the differences in RBS strength - if we compare test device 1 and 4 which both contain the same promoter, J23101, but different ribosome binding sites (test device 1 containing B0034 and test device 4 containing J364100). Looking at the comparison between test device 1 and test device 4 it can be seen that test device 4 is only fluorescing at roughly 40% the rate of test device 1 and so the B0032 ribosome binding site is about 2.5 times as strong as the J364100. However, if we compare test device 2 and 5, which both have the same promoter –J23106- but different RBS, in these it appears that the B0032 RBS is 5 times stronger than the J364100 RBS. Furthermore, this value increases even more when comparing test device 3 and 6- both containing the J23117 promoter and in this case, is appears that the B0032 RBS is almost 20 times as strong as J364100.

Next, looking at the relative strengths of the promoters, test device 1, 2 and 3 all contain the B0032 ribosome binding sites but different promoters so can be used to compare the efficiencies of the promoters. Test device 1 contains the J23101 promoter, 2 the J23106 promoter and 3 the J23117 promoter. In the case of these test devices the J23101 promoter appears to be 3 times as strong as J23106 and almost 20 times as strong as J23117. Looking at the other trio that can be used to compare promoter strengths – test devices 4, 5 and 6- that all contain the J364100 RBS, from these J23101 appears almost 7 times stronger than J23106 and over 100 times stronger than J23117.

Discussion

Firstly, in regard to the strengths of the promoters our results corroborate what was already known about the strengths of the promoters, with J23101 being the strongest and J23117 being the weakest. However, the relative strengths of them seems to ask more questions than it answers from previous results. It had been previously seen that when the promoters relative red fluorescent protein expression levels were studied J23101 was 1.5 times as strong as J23106 and around 10 times stronger than J23117[3] however when we compared them using GFP our relative strengths of expression, although they followed the same pattern, did not match what was previously seen. Additionally to this the pattern of relative strengths didn't match when looking at the promoters when the were paired with B0034 compared to when they were paired with J364100. The same can be said for the strengths of the RBS - with B0034 appearing the strongest in all cases but how much stronger it appears compared to J364100 depends on the promoter it is paired with. One possible explanation for the promoters relative strengths changing between the two different RBS and visa versa is that the promoters and RBS don’t work completely independently and that it is more the interactions between the two that is causing differences in the patterns of strengths.

When the fluorescence was normalised to OD the standard deviations at time point 0 were very high (due to dividing low fluorescence by a very low OD600) and so this indicates that this isn’t a good time point to take base fluorescent measurements on as the results seem to be so variable. Therefore, a time point closer to 4 hours should be used to increase reliability. The location of the sample within the plate can affect the growth rates as the temperature can vary between the outer wells and the centred wells. Ideally, the outermost wells should be left empty and the samples should be randomly placed in the innermost wells to reduce for errors due to this factor [4]

We also found that for the purpose of studies such as the InterLab where a wide range of data will be taken and collated it is important that all research groups use the same derivative of DH5α E. coli and that they ensure that all plasmids are strictly in monomer form as dimers behave unreliably. Full results and explanation for the different strain type and dimer plasmids can be seen on the Measurement page.

iGEM Glasgow 2017 were proud to take part in the 2017 InterLab study and look forward to seeing how the data will look when it is collated from all teams and how this study will impact the scientific world.

References

- ↑ Mutalik, V., Guimaraes, J., Cambray, G., Lam, C., Christoffersen, M., Mai, Q., Tran, A., Paull, M., Keasling, J., Arkin, A. and Endy, D. (2013). Precise and reliable gene expression via standard transcription and translation initiation elements. Nature Methods, 10(4), pp.354-360.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Anon, (2017). [online] Available at: https://static.igem.org/mediawiki/2017/8/85/InterLab_2017_Plate_Reader_Protocol.pdf [Accessed 16 Jul. 2017].

- ↑ Parts.igem.org. (2017). Part:BBa J23101 - parts.igem.org. [online] Available at: http://parts.igem.org/wiki/index.php?title=Part:BBa_J23101 [Accessed 28 Oct. 2017].

- ↑ 2016.igem.org. (2017). Team:Exeter/Interlab - 2016.igem.org. [online] Available at: https://2016.igem.org/Team:Exeter/Interlab [Accessed 10 Oct. 2017].