What did our model achieve?

We achieved two main goals;

We designed a mathematical model for phage-bacteria interaction. This work expands upon existing models

to encompass variation in lysis timing of phages.

We applied our mathematical model to our chemostat system and determined ideal parameters for our

experimental project. We then utilized these parameters when implementing our physical system

(see results below).

All our code is available on our Wiki.

Se functions.cpp,

classes.cpp,

header.h

and main.cpp.

Modelling phages

Phages are infectious viruses that kill certain bacteria. When a phage finds a bacterium to infect, it attaches and inserts itself into the bacterium, and hijacks the bacterium’s cellular machinery to create lots of copies of itself. After a short period, the new phage particles will burst out of the now dead bacterium (lysis), ready to infect new bacteria. We used existing mathematical models of this interaction, and expanded upon them.

A simple model for one bacteria and one phage in a closed system is easily obtained. As a starting point, we used the model detailed in [1] without mutation. This model and all following models assumes mass-action kinetics between bacteria and phages; the rate of infection is proportional to the product of the concentrations of the two.

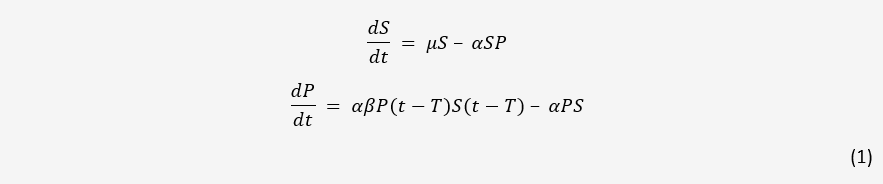

Here, S and P are the concentration of bacteria and phages in the system respectively. µ is the

growth rate of bacteria, α is the adsorption rate of phages, β is the number of new phages produced

per infection, and T is the average lysis time of an infected bacterium. This model serves as the

basis for phage-bacteria interactions in many papers.

The bacterial rate of growth µ is not a constant. For all following models, we assume µ follows

Michaelis Menten kinetics;

Where N is the concentration of growth-limiting nutrient, µ_max is the max growth rate, and K_m

is the half-velocity constant; the nutrient concentration at which µ = µmax/2.

This model assumes a constant lysis time; every phage infects a bacterium for exactly T units

of time before lysing. To create a more realistic model, we adapted the model to deal with variable

lysis times; we assume a lysis probability function normally distributed around the average lysis

time T. This requires an additional variable I, a vector function that keeps track of all infected

bacteria and when they were infected. By convoluting the probability distribution function f of

a bacterium lysing with the infection vector I, we obtain the number of new lysed bacteria at

time t.

Here, bacteria grow according to Michaelis-Menten kinetics with N designating the concentration of growth-limiting nutrient, and y is a stoichiometric conversion factor between nutrient and bacterial mass. The infection vector I is updated by adding new infections at current time t and subtracting the convolution of I with the probability distribution f. Note that if using discrete time steps to solve system (3), I effectively expands an entry every time step with the new entry housing I(t).

f is given by the ration between g, the PDF of the lysis time, and 1-G, the inverse CDF of lysis time. Dividing the PDF with the inverse CDF adjusts the distribution to account for lysed infected bacteria. Our modelling assumes g follows a normal distribution N(T, σ2) around the average lysis time with a variance σ2. However, if desired, any valid probability distribution can be inserted in the expression for f.

Modelling chemostats

Our motivation for modelling phage-bacteria interactions is to provide our wet lab with appropriate parameters for accomplishing our goal. That is, using our chemostat system to evolve a phage capable of killing a select strain of bacteria. We described our system mathematically and wrote a C++ program to numerically solve the system of integro-differential equations. Matlab was used for plotting. Using this, we determined parameters to optimally evolve a capable phage and test out project.

A single chemostat with one bacterial strain and continuously supplied medium can be modelled by the following differential equations adapted from (3) without phage.

Where c_N is the concentration of the continuously supplied medium, Q is the volume of medium supplied per unit time, and q is the exchange rate, Q/V (also called dilution rate). This is an important quantity in chemostat modelling, since the equilibrium growth rate of a bacteria in a chemostat is equal to the exchange rate. It is therefore the major independent variable used to control the chemostat.

Fig. 1 Bacterial growth in chemostat measured by OD600.

Fig. 1 shows the bacterial growth curve for a chemostat system with typical parameters (see

constants list). The figure shows the typical elements of a bacterial growth curve, with a

lag phase, exponential growth, and stationary phase. Since chemostats are continuously supplied

with new medium and flushed, bacterial death can safely be neglected.

The state system of a chemostat continuously supplied with two bacteria and two phages is shown

below. Our goal is to start with a phage (P1) incapable of infecting a certain bacteria (S2) and

continue feeding it with a bacteria it can infect (S1) until it evolves into a phage (P2) capable

of infecting S2.

In this system of equations, Q designates the total flow in and out of chemostat, where Q1 and

Q2 are the flows of bacteria S1 and S2 respectively. The phage production is multiplied by e-qT

to account for washout of infected bacteria. The fitness parameters of the both bacteria and both

phages are assumed to be the same, although obviously this model can be expanded to remove this

assumption fairly easily (it necessitates three infection vectors).

A differential equation solver allowing for time-delay convolution proved hard to find, so we

wrote our own 4th order Runge-Kutta solver. We originally wrote the script in Matlab, but moved

to C++ after it became clear the script was computationally-intensive and needed to run faster.

Fig. 2 Number of bacteria of strains S1 and S2 alongside number of phages P1 and P2 over 12 hours. Log scale.

Fig. 2 shows a simulation of equation set (6) with typical parameters (see constants list). All

four biological species are graphed over 12 hours. However, this model does not allow for the

mutation of bacteria and phages which our system relies on. In order to obtain graphs such as

Fig. 2 it was necessary to initialize with a small number of phage P2 in the system. Our system

mostly assumes mutations that give rise to P2 will not occur before steady state, so this is a

limitation of the model.

However, we still managed to put the model to good use by optimizing quantities which should

maximize potential mutation. We wish to maximize the speed at which our system evolves P2. In

a chemostat with a single phage and bacteria at steady state, this is given by

This factor expressed the total production of new phages that survive long enough to produce new

phages. We found the exchange rate that maximizes this factor, and used it our experimental system

(see applied results below).

In addition to evolving phages, we also needed to evolve resistant bacteria for control testing

in a timely fashion. In this case, the quantity to be maximized is the total division rate of

bacteria µS. We also found the exchange rate that maximizes this factor and used it to evolve a

resistant bacteria strain (see applied results below).

Applied results:

We used our mathematical model and numerical simulations to maximize the efficiency of our wetlab system. We determined the optimal exchange rate of a chemostat to maximize various desired qualities, and utilized our results in implementing our physical project.

To quickly evolve phage-resistant bacteria, we plotted the total division rate of the bacteria as a function of the exchange rate.

Fig. 3 Maximizing the total bacterial division rate as a function of exchange rate. A maximum occurs at around 1.25 h-1.

Fig. 3 shows this plot. There is clearly a maximum around an exchange rate of 1.25 h-1.

This should maximize the speed at which bacteria develop resistance to a phage in the chemostat.

However we also wanted to check that this exchange rate would not cause any problems. The photometer

we made to measure bacterial concentration (see hardware) was less sensitive at lower concentrations

(OD600), so wanted to make sure the OD600 would not be too low at this exchange rate. We also wanted

to make sure the system would not take too long to come to steady state.

Fig. 4 Steady-state OD600 and time to reach steady-state plotted as functions of the exchange rate.

Fig. 4 shows that these concerns were unwarranted at an exchange rate of around 1.25 h-1, with

an equilibrium OD600 of 1.4, and equilibrium reached after <20h. We also see at an exchange rate

above 1.8 h-1, the bacteria are unable to keep up and are washed out. For these reasons, and

exchange rate very close to the theoretical optimum of 1.25 was utilized when implementing our

physical project.

After obtaining phage-resistant bacteria, we wanted to determine the best exchange rate for

evolving a phage to overcome this resistance. Using the quantity determined to maximize this

(see modelling chemostats above), we maximized this quantity.

Fig. 5 Total number of phages pr. hour that survive long enough to produce new phages as a function of exchange rate. Numbers at steady state.

Fig. 5 shows that the optimum exchange rate of phage evolution is significantly higher than for bacterial evolution; around 2.0. The exchange rate here can be above the washout exchange rate in Fig. 4 because bacteria are being continuously pumped into the chemostat. This exchange rate was utilized when implementing our physical project.

Constants list

The constants we used for modelling were chosen by a mix of reviewing previous research, empirical observations, and considerations of what our system was physically capable of. Some of the constants are not tested as thoroughly as we would have liked due to time limitations. A more thorough exploration of how these constants are interconnected and influence our simulations would be an interesting topic of further research.

Table 1. Important modelling constants. These values were generally used as defaults during simulation.

| Chemostat volume (L) | 400 |

| Limiting nutrient inflow concentration (mg/L) | 70 |

| Stoichiometric conversion nutrient to bacterial mass | 4.0*10-15 |

| Maximum bacterial growth rate (/h) | 2.5 |

| Michaelis-Menten constant (mg/L) | 25 |

| Inflow bacterial concentration (/L) | 3.0*1010 |

| Phage adsorption rate (phage-1cell-1mL-1h-1) | 6.0*10-9 |

| phage burst size | 100 |

| average lysis time (h) | 1.0 |

| Standard deviation of lysis time (h) | 0.05 |

Bacterial kinetic constants were set by examining previous research (2) and empirical

considerations of observation of the bacteria we used. Phage constants were set by examining

previous research (3) and observation of the phages we used.

References

- Cairns, Timms, Jansen, Connerton, Payne; “Quantitative Models of In Vitro Bacteriophage–Host Dynamics and Their Application to Phage Therapy”, PLOS pathogens, published Jan. 2, 2009. http://journals.plos.org/plospathogens/article?id=10.1371/journal.ppat.1000253, accessed 01/11/17

- Schule, Lipe; “Relationship between substrate concentration, growth rate, and respiration rate of Escherichia coli in continuous culture”, Archives of microbiology, March 1964, Issue 1, pp 1-20.

- Shao, Wang; “Bacteriophage Adsorption Rate and Optimal Lysis Time”, Genetics, 2008 Sep; 180(1): 471–482.